Cut JPMorgan some slack, its Indonesia upgrade was sound

Change Size

Indonesia recently terminated all of its deals with the JPMorgan Chase Bank, NA, a subsidiary of New York-based JPMorgan Chase, after it published a research note that downgraded the country two notches from the “overweight” to “underweight” position. -- Bloomberg (Bloomberg/Bloomberg)

Indonesia recently terminated all of its deals with the JPMorgan Chase Bank, NA, a subsidiary of New York-based JPMorgan Chase, after it published a research note that downgraded the country two notches from the “overweight” to “underweight” position. -- Bloomberg (Bloomberg/Bloomberg)

D

on't leap to conclusions about JPMorgan Chase & Co.'s decision to upgrade its assessment of Indonesia's stock market.

The New York-based bank has elevated internal compliance to nuisance levels in Asia since a scandal over its hiring practices in China broke three years ago, people who work at JPMorgan tell me. In such an environment, the Indonesia rating change was probably just what the analysts said it was: a tactical shift.

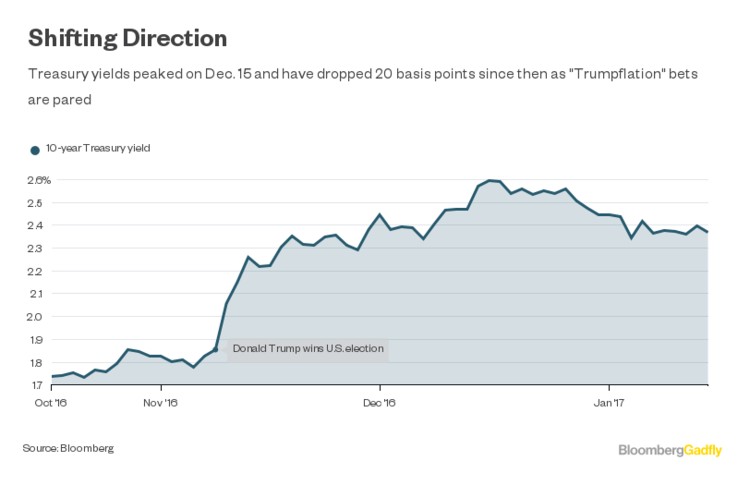

Objectively, the reasons look solid. On Nov. 13, when JPMorgan's equity research team said it was changing its assessment of Indonesian stocks to a "sell," the bank's analysts predicted that emerging markets would suffer outflows and U.S. 10-year Treasury yields would rise. That was a tactical move, or a position that typically can be reversed in a few months, unlike a longer-term, strategic change.

Both forecasts proved correct. Exchange-traded funds that focus on Asia excluding Japan lost a net $423 million in the past three months, according to Bloomberg data. The yield on the U.S. bond benchmark peaked on Dec. 15 at 2.6 percent, 45 basis points higher than its 2.15 percent level when JPMorgan decided it was time to reduce exposure to the Jakarta Composite Index. Since Dec. 15, the yield has retreated about 20 basis points.

Emerging markets have been receiving more love since the new year started, after what the International Institute of Finance called the worst year for portfolio flows since the 2008 crisis. In the first 16 days of January, a couple of billion dollars have flowed into Asian ETFs, excluding China, Bloomberg data show.

The premium to net asset value of the iShares MSCI Emerging Markets ETF, a good gauge of which way money is going, has been mostly positive in 2017, having been deeply negative after the U.S. election.

So it's easy to see why JPMorgan equity analysts would have changed their views on Indonesia. The bank is hardly alone: The country has been mentioned as one of the darlings for 2017 in every year-ahead outlook meeting I've attended in the past two weeks.

The Indonesian government stopped doing business with the U.S. bank after its earlier bearish call. Just to settle the issue, let's consider what JPMorgan was missing out on after it was cut off from bond underwriting for Jakarta.

The bank participated in only three large foreign-currency transactions in the country last year, of which only one involved the government. That one, a 3 billion euro ($3.2 billion) sale of seven- and 12-year bonds, was shared with three other institutions.

Even assuming the sovereign paid 50 basis points as a fee to the underwriters (a more usual level would be 25 basis points or less), JPMorgan would have made about $4 million. In investment banking, that's not a lot. Debt and equity are separate businesses within the bank, so none of that money is likely to have ended up in the pockets of stock analysts via bonuses.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission has very clear and strict rules on analyst independence (explained well in this piece by Bloomberg View's Matt Levine). Having paid $264 million to U.S. regulators to settle the China hiring case in November, JPMorgan was hardly likely to risk another controversy so soon.

The Indonesian government, meanwhile, has to make up its mind. Either it wants financial analysts to be independent, and dealings with the country to be “based on professionalism, integrity and avoiding conflicts of interest,” as the finance ministry told banks last week, or it wants everyone to dance to its tune.

If Jakarta keeps meddling, international banks may decide to pull out of the country of their own accord, whether or not they have been banned. As of December, 38 percent of Indonesia's local-currency government bonds were owned by non-residents.

Guess who has the most to lose if global lenders start to leave?

***

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

---------------

We are looking for information, opinions, and in-depth analysis from experts or scholars in a variety of fields. We choose articles based on facts or opinions about general news, as well as quality analysis and commentary about Indonesia or international events. Send your piece to community@jakpost.com. For more information, click here.