Darwin's 'strangest animal ever' finds a family

Charles Darwin, Mr. Evolution himself, didn't know what to make of the fossils he saw in Patagonia so he sent them to his friend, the renowned paleontologist Richard Owen.

Change Size

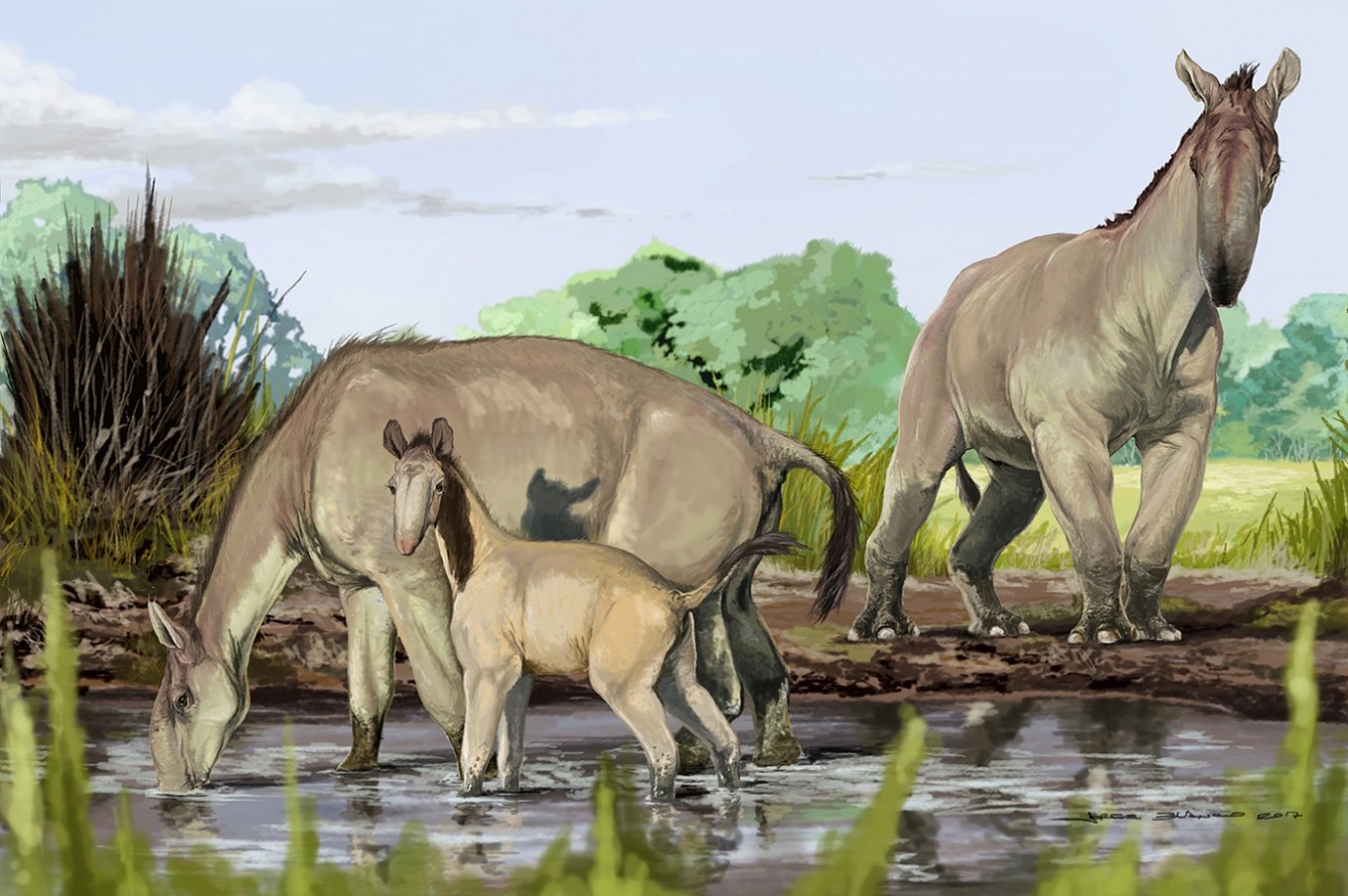

This image received from the American Museum of Natural History via Nature Research Press Office on June 27, 2017 shows an Artist reconstruction of Macrauchenia patachonica. Charles Darwin, Mr. Evolution himself, didn't know what to make of the fossils he found in Patagonia so he sent them to his friend -- and renowned paleontologist -- Richard Owen. Owen was stumped too. Little wonder. "Imagine a camel without a hump, with feet like a slender rhino, and a head shaped like a saiga antelope," said Micheal Hofreiter, senior author of a study released on June 27, 2017 that finally situates what Darwin called the "strangest animal ever discovered" in the tree of life. Macrauchenia patachonica -- literally, "long-necked lama" -- also had a trunk-like snout, and nostrils high on its skull between the eye sockets. (American Museum of Natural History/AFP /Jorge Blanco)

This image received from the American Museum of Natural History via Nature Research Press Office on June 27, 2017 shows an Artist reconstruction of Macrauchenia patachonica. Charles Darwin, Mr. Evolution himself, didn't know what to make of the fossils he found in Patagonia so he sent them to his friend -- and renowned paleontologist -- Richard Owen. Owen was stumped too. Little wonder. "Imagine a camel without a hump, with feet like a slender rhino, and a head shaped like a saiga antelope," said Micheal Hofreiter, senior author of a study released on June 27, 2017 that finally situates what Darwin called the "strangest animal ever discovered" in the tree of life. Macrauchenia patachonica -- literally, "long-necked lama" -- also had a trunk-like snout, and nostrils high on its skull between the eye sockets. (American Museum of Natural History/AFP /Jorge Blanco)

C

harles Darwin, Mr. Evolution himself, didn't know what to make of the fossils he saw in Patagonia so he sent them to his friend, the renowned paleontologist Richard Owen.

Owen was stumped too. Little wonder.

"The bones looked different from anything he knew," said Michael Hofreiter, senior author of a study published Tuesday in Nature Communications that finally situates in the tree of life what Darwin called the "strangest animal ever discovered".

"Imagine a camel without a hump, with feet like a slender rhino, and a head shaped like a saiga antelope," Hofreiter, a professor at the University of Potsdam, told AFP.

Macrauchenia patachonica -- literally, "long-necked llama" -- also had a long rubbery snout and with its nostrils high on the skull just above its eyes.

For nearly two centuries, biologists and taxonomists argued over the pedigree of this bizarre beast, which weighed 400 to 500 kilos (850 to 1100 pounds), lived in open landscapes, and snacked on grass and leaves.

But its mixed bag of body features, and a paucity of DNA evidence, made it nearly impossible to determine whether M. patachonica was truly related the llama after which it was named.

As it turns out, not really.

Read also: Tempeh science taken to outer space

- Evolutionary dead end -

A new kind of genetic analysis revealed that Macrauchenia was more akin to an ancient placental order known as Perissodactyla that includes horses, rhinos and tapirs.

"We had a difficult problem to solve here," said lead author of the new study Michael Westbury, also at the University of Potsdam.

"When ancient DNA is so degraded and full of unwanted environmental DNA, we rely on being able to use the genomes of close relatives as a kind of scaffold to reconstruct fossil sequences," he said in a statement.

But Macrauchenia -- itself an evolutionary dead end -- didn't have any close cousins that we know of.

To solve the puzzle, Westbury and a 20-strong team of scientists used mitochondrial DNA extracted from a fossil found in southern Chile to decode the extinct mammal's origins.

Inherited from the mother alone, the mitochondrial genome is smaller and has more copies in the cell -- and thus in fossils -- than DNA from the more complex nuclear genome, Hofreiter explained.

Read also: New antibiotic potentially big in fighting drug-resistant bacteria

"Mitochondrial DNA is very useful for evaluating the degree of relatedness among species," he said.

The team eventually pieced together almost 80 percent of the total genome, making it possible to situate Macrauchenia in an evolutionary timeline.

The creature's lineage, they concluded, split with that of modern perissodactyls some 66 million years ago, about the same time a massive asteroid slammed into Earth and wiped out non-avian dinosaurs.

Macrauchenia survived until the late Pleistocene, 20,000 to 11,000 years ago.

"Why it disappeared we really don't know -- it is still an open question whether it was humans, climate change, or a combination of the two," said Hofreiter.