Short Story: A Family Portrait

What’s the use of digging through somebody’s past when that somebody doesn’t even want to, nor have the goodwill to, connect with you?

Change Size

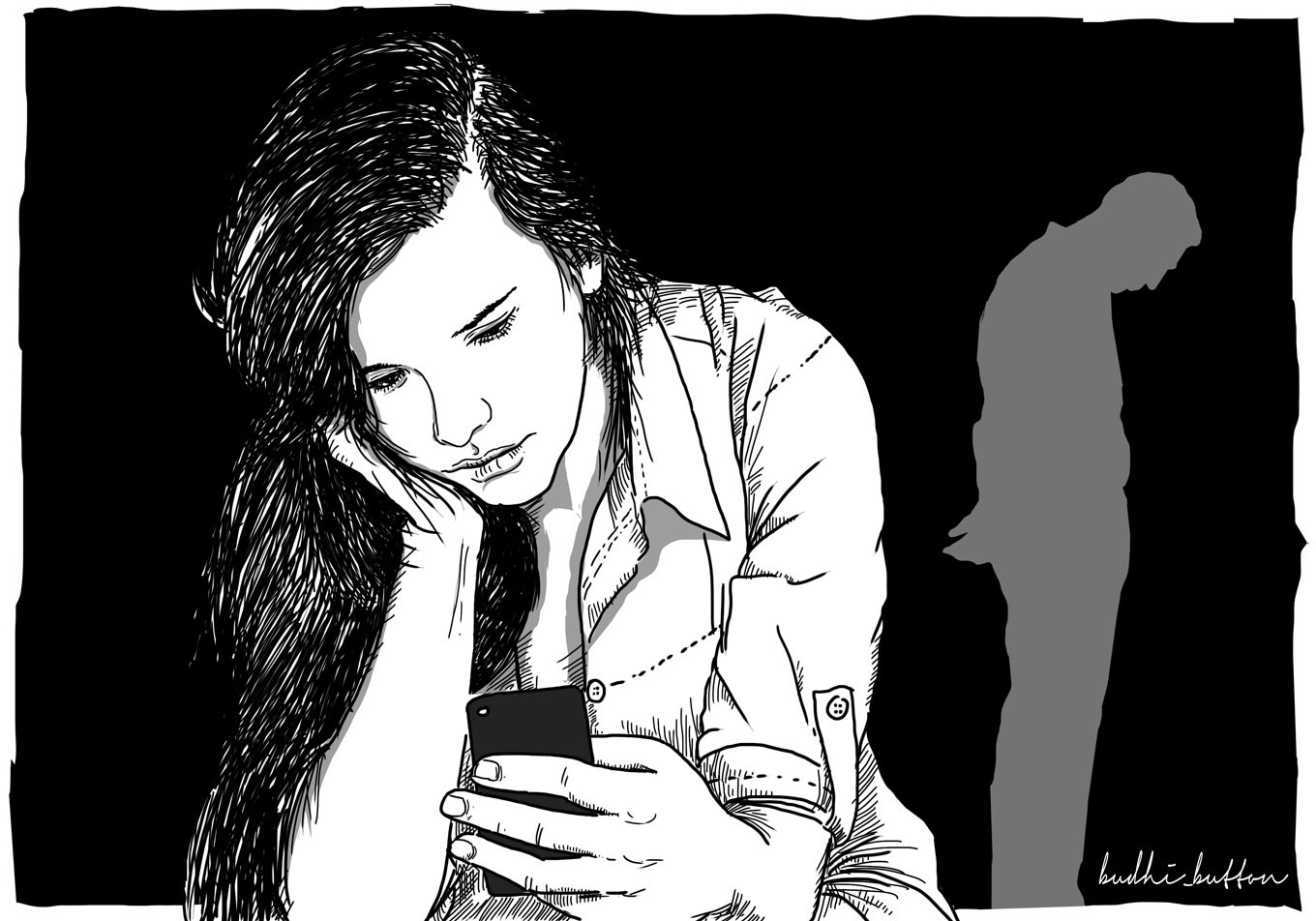

I did spend a huge amount of time on my phone — scrolling pictures on Instagram vehemently — looking for my stepsisters from my estranged father whom I had never even met. (JP/Budhi Button)

I did spend a huge amount of time on my phone — scrolling pictures on Instagram vehemently — looking for my stepsisters from my estranged father whom I had never even met. (JP/Budhi Button)

O

n the second day of Eid celebrations — a day that’s supposed to be spent visiting family— I sat alone in a café for hours under the guise of doing my assignments. No one asked me how I had an assignment during a holiday, so I could be lying. I wasn’t lying though, I did have an assignment, but that’s a different story. However, I did spend a huge amount of time on my phone — scrolling pictures on Instagram vehemently — looking for my stepsisters from my estranged father whom I had never even met — which is only normal if I was a character in a coming-of-age movie.

This is complicated: I know I’m not going to find her, nor will I find my biological father online in a day, two or five. Even if I managed to find a supposed stepsister or two, how would I know they’re the right ones? The information my mother gave me about these girls is vague, at best; she wasn’t even sure how many of them are out there. Of course, that’s what you get when your mother randomly drops the bomb in the most uneventful and unexpected situation.

*

I was lying down after a shower in my mother’s bedroom with a stack of pillows below my head, pressing my chin against my chest, when suddenly she pinched me and said, “You’re so fat. I think you got that from your father.” I didn’t budge because I just don’t most of the time. Here we go again, I thought. I knew I looked uninterested and I felt like I was, but every time this issue was brought up I automatically took a mental note. This is one of my favorite traits, I always remember little details that aren’t really important.

For instance, I remember the ethnicity of my biological father. This was something I sort of asked my mother directly. It was in the fourth grade. In our citizenship education class we had a chapter about ethnicities and back then when ethnic issues weren’t discussed as often, it was still normal for my teacher to ask everyone in the class what their ethnicity was. I panicked. Everyone seemed to know their ethnicity and I barely managed to grasp this concept. Luckily, I sat in the back, so I had some time to think. I nudged my seatmate and quietly asked, so as to not let the teacher notice my sudden wave of distress, “How do you know what ethnicity you are?”

My friend, who was quite close to me and knew a little about the “father situation” answered me with worried eyes, “It’s the same as your father’s.”

I had two options: I could lie or I could admit my lack of knowledge on the matter and bring up the drama of my father’s absence. Naturally, I lied — although that isn’t quite the right word for it. I felt inadequate being in a classroom full of people who knew exactly who they were; and my way of coping with that particular feeling was to say things that weren’t true. I still do this. For example, I have a habit of introducing myself using a false pronunciation because my name is “white” and the correct pronunciation would make me look fraudulent — the foreign name does not match my local appearance.

That day, I asked my mother in the car, after she had picked me up from school: “Mom, what’s my ethnicity?”

“We’re Javanese,” she said lightly.

“My friend said that our ethnicity comes from the father’s side,” I went on without looking at her.

“We’re Javanese,” she repeated herself.

That night, my mother called me into her bedroom. Well, this can’t be good. She then told me that my father came from Manado, which makes me Manadonese.

Night came. I was invited to my mom’s room. This can’t be good. A little less random and casual than she does nowadays, she told me that my father was Manadonese. I imagined how hard it must have been for her to share that information with me; so I didn’t ask further questions. I don’t know why I was so indifferent about this whole thing. I remember in the second grade when my teacher asked me to write down the names of our family members and I left the part where my father’s name was supposed to be completely blank. My teacher yelled at me, thinking I had either failed to understand his instructions or simply too dumb to recall my parent’s name.

However, I didn’t try to explain it. I stayed silent — which is my go-to response to all things that are related to my mother’s past.

After revealing my father’s ethnicity, my mother continued her information-sharing session by claiming the sinetron (soap opera) actress I admired was actually my father’s niece — this meant she was my cousin. Now that’s interesting.

*

My mother stopped pinching me and said, “Too bad you have never met your father. Well, what can I do? He doesn’t want to see you.”

Nice, I thought. I could do without that bit of information. So … um, thanks, Mom.

I rose from my mother’s bed and walked toward the mirror. I felt tears coming on. Not today, please. Then it went away.

Just when I thought I was safe, my mother blurted out, “He has a daughter, too. Or are there two?”

I let out a snarky two-second laugh just to show I was unfazed and waited for my mom to leave the room. When she did, I moved to my cousin’s room that had once been mine. Then I cried; and in the mirror next to the bed I saw how pathetic I looked. Nope. You’re fabulous. You got this. I, like every lead character in an empowering chick flick I could recall, went window shopping and café-hopping shortly after that.

That was the day I realized my competitive streak. What if these potential stepsisters are more beautiful than I am, or smarter and more privileged? I couldn’t think of a single reason why I would want to meet them.

*

I was left feeling stupid for not having demanded more information when it was normal to do so. As a kid, wanting to know who your father is natural. As a young adult, it seems dramatic and unnecessary. Yet I couldn’t shake the curiosity. There was also the pressure of wanting to hold on to something. A label, perhaps. Or family roots.

Eid gave me the chance to look at family pictures, searching for the face of my supposed celebrity cousin. I scrolled upon pictures of different twenty-something girls, some of whom are blessed with thousands of followers. I myself have less than 400 followers, which classifies me as an unsociableperson. I don’t like these girls already. I put my phone down, held it again, frantically comparing my nose and eyes to theirs and repeated the process again and again.

I stared at one picture of a girl whose facial features seemed to correspond well with my mother’s descriptions of my father. So I accessed her digital photo albums, hoping to find my father’s face among the unfamiliar faces — but the drama I waited for did not materialize. Nothing came up. Nevermind, I thought.

What’s the use of digging through somebody’s past when that somebody doesn’t even want to, nor have the goodwill to, connect with you? And what would I say to him, anyway? Would a simple greeting like “Hey dad” do any good?

Probably not.

As more and more of my mother’s family came to visit our house for Eid celebrations, I whisked away the thought of ever finding or searching for my father and his daughters. Or, to be precise, my imaginary parent and siblings.

The thing is … if I ever found my father and his new family, me showing up in their life, the life I never knew they had, the life I would crave for myself — I would most likely ruin it.

So I turned off my phone, asked for the check and went about my regular life, in which my father does not exist and my stepsisters — whoever and wherever they are — will remain unknown to me.

C’est la vie.

***

Rachel Diercie is an undergraduate student at the University of Indonesia.

____________________

We are looking for contemporary fiction between 1,500 and 2,000 words by established and new authors. Stories must be original and previously unpublished in English.

The email for submitting stories is: shortstory@thejakartapost.com

We are no longer accepting short story submissions for both online and print editions. New submissions to shortstory@thejakartapost.com will not be published.