Museum Sekartaji: World's only 'Wayang Beber' Museum

Narrative visual: A painting depicts the story of Jaka Tarub, a legend in the series of Panji

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

N

arrative visual: A painting depicts the story of Jaka Tarub, a legend in the series of Panji. The work was created by Hermin Istiariningsih, a painting maestro from Surakarta, Central Java.

Not many people today know about wayang beber, a traditional form of puppetry that uses painted scrolls as its storytelling medium, but a man from Bantul, Yogyakarta, is determined to keep the tradition alive.

Indra Setiawan has funded and set up a museum dedicated to wayang beber next to his house in Kanutan village in Bantul regency, Yogyakarta.

A 90-square-meter Javanese limasan (pyramidal house) houses the museum’s main display room.

The 31-year-old has named the museum Sekartaji, an acronym formed from semedi (meditation), cakra (disk), jawata (gods) and aji (charm). The words also form a chronogram for 1951 in the Javanese calendar, which is equivalent to 2017 in the Gregorian calendar, the year the building was erected.

“Many museums also exhibit scroll puppetry, but this museum is the only one in the world that displays a wayang beber collection,” Indra told The Jakarta Post.

Like other wayang arts, wayang beber is performed by a dalang (puppet master). In wayang beber, however, the dalang unrolls painted scrolls of puppets that illustrate the scenes of the story he is narrating. Four scenes are painted on 2-square-meter sheets of paper that are inserted in a vertical scroll theater that faces the audience.

The dalang, sinden (female vocalist in a gamelan orchestra) and a gamelan orchestra are positioned behind the scroll theater. The dalang unrolls six scrolls in succession to tell the tale to the accompaniment of gamelan music.

A show typically lasts 1.5 hours and presents the Panji princedom legends, notably those of Panji Asmorobangun and Dewi Sekartaji. UNESCO recognized these stories that spread to Thailand and Cambodia as a World Cultural Heritage in 2017.

RM Sayid, a member of the Surakarta Puppetry Expert Council, writes in his Sejarah Wayang Beber (The history of wayang beber), published in 1980, that this form of scroll puppetry originated in 1145 during the rule of King Suryowisesa in the Jenggala Kingdom of East Java. The king himself painted puppet figures on palmyra leaves.

In the Majapahit Kingdom, Raden Jaka Sesuruh created a series of wayang paintings during his reign on large pieces of dlancang Jawi (Javanese paper) that were produced in Ponorogo, and finished them in 1283. When they were presented as puppet theater, the rolls of paper were spread out — beber in Javanese — and the scroll puppetry performance and the paintings have since been called wayang beber.

“Wayang beber is a very old art, the precursor of the wayang kulit [shadow puppet theater] we know today,” said Indra.

After gaining high popularity among both the nobility and the common people, wayang beber began to fade during the Demak Kingdom, when early Islamic preachers introduced wayang kulit. Today, only the people of Gunung Kidul in Yogyakarta and Pacitan in East Java still perform wayang beber.

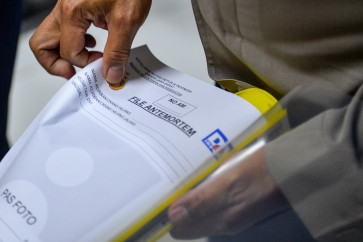

Museum Sekartaji exhibits the painted scrolls that are used in wayang beber shows, including the works of wayang beber master painters from Surakarta such as Hermin Istiariningsih, Indra’s mentor, and Dani Iswaradana Wibowo. Not all pieces in the museum’s collection of 35 scrolls are on display, due to the limited space.

“Visitors can learn about the history and creative process of wayang beber and watch performances,” said Indra. “The museum is open all day. Whenever a visitor arrives to see the collection, we will let them in.”

The museum has already welcomed about 700 visitors since it opened in October last year.

One recent visitor, Asies Sigit Pramujo, appreciated the fact that the museum existed. “With this museum, children can learn about wayang beber themselves,” Asies said. “While Europeans had oil painting, we were already painting wayang beber, so we were no less conversant [in the arts],” he added.

Indra is now saving money to expand and improve his museum. He does this in part by fulfilling orders for wayang beber paintings that depict the spiritual journey of the individual who commissioned them.

“I call such paintings spiritual wayang beber art,” he said.

— Photos by JP/Bambang Muryanto