Viral coup video highlights RI-Myanmar links

Some say Myanmar’s situation echoes Indonesia’s New Order past

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

A day after Myanmar’s armed forces, the Tatmadaw, shocked the world by overthrowing its civilian government on Monday, an absurd video reportedly capturing footage of the coup in-the-making was going viral on social media.

In the video, a Burmese woman was doing morning aerobics exercises to the tune of a campy beat, oblivious to the fact that rows of military vehicles were storming into the Myanmar parliament building in the background.

The irony did not stop with the woman’s nonchalant attitude to what was unfolding behind her, as Indonesian netizens quickly pointed out that the song she was dancing to might as well have been expressly made for the situation.

The woman in the video, Khing Hnin Wai, was dancing to the lively electronic beat of an Indonesian song titled “Ampun Bang Jago”, which roughly translates to “Ease up, Mr. Hotshot” – a phrase that has been used as a retort to arrogant people and self-righteous figures of authority.

More importantly, the tune was recently elevated to the status of a protest song, carrying with it a message of resistance against the establishment as waves of protest against the omnibus bill spread through Indonesia last year. Activists and watchdogs documented hundreds of cases of alleged police brutality during the riots in October.

It was a far cry from the humble beginnings of the video game jargon and expression to dismiss snobs.

“Previously it was only used during demonstrations, so we were already used to it. But now we’re talking about a coup, which is taking power from the government by force, […] and that’s really crazy,” Jonathan Dorongpangalo, one-half of the singer-rapper duo who made the disko tanah song famous, told The Jakarta Post on Tuesday.

Jonathan and Everly Salikara are musicians from North Sulawesi who launched the song in September and quickly gained popularity through TikTok and YouTube.

While the subtext of the song, combined with the Burmese lady’s accidental recording of the putsch, has made Myanmar’s crisis easily relatable to Indonesia’s netizens, it only scratches the surface of bilateral engagement by the largest democracy and de facto leader in Southeast Asia.

Indonesia and Myanmar are both multiethnic nations from the region that share similar trajectories in the struggle for independence in the 1940s and the experiments on democracy in the 1950s, foreign policy scholar Dewi Fortuna Anwar said.

“Both countries failed in the experiment of the liberal parliamentary democracy, which was then replaced by military power,” she told the Post on Tuesday.

Nowadays, Indonesia looks on at Myanmar as a shadow of its New Order past, ripe with its own complicated historical, political and sociocultural backstory.

Indonesia’s New Order regime was established when military general Soeharto wrested power by utilizing a coup in 1965 that is still hotly debated today. Soeharto’s rule was only brought down in 1998 by student protests.

Similarly, the Tatmadaw has managed to hold on to power for more than five decades, protected by a constitution that it drafted itself and gave it significant control over all government branches – not unlike the “dual-function” of Indonesia’s armed forces during the New Order.

“When we engage with Myanmar officials, there is this joke that Myanmar always follows whatever Indonesia does – but only for the wrong things,” said I Ketut Putra Erawan, executive director of the Institute for Peace and Democracy (IPD).

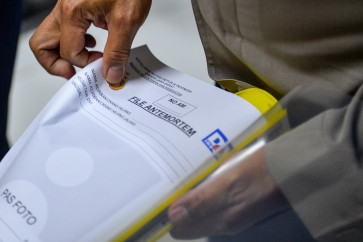

As one of the few Indonesian organizations that played a significant role in assisting Myanmar’s recent democratic transformation, the IPD has been helping the government in Naypyidaw to hold elections – such as the one in 2015 that saw Aung San Suu Kyi seize power – by training election officials and modeling Myanmar’s election system on Indonesia’s own.

Since 2008, Indonesia has also organized the annual Bali Democracy Forum that Myanmar actively participates in, opening up discussion on how to help it transition to a more democratic nation.

“We approached Myanmar saying that the road to democracy is indeed long and that we have to count on a lot of contradictory forces, but it will be beneficial for long-term sustainability,” Ketut said on Tuesday.

Myanmar’s military gave up some of its powers in 2011, which led to the creation of a semi-democratic system. Even so, many problems still remained, including outsized military influence from the 2008 constitution, as well as a host of economic woes and interethnic tensions.

The 2015 election was the first openly contested election held in Myanmar since 1990, and Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy had won it, although the Nobel peace laureate was still barred from the presidency due to a constitutional provision aimed specifically at her.

Still, she got around it by making herself state counsellor, but the power-sharing deadlock between her party and the military had built up tension and resentment for five years that eventually led to Monday’s coup, Ketut said.

“Power sharing is the main problem post-election; who will be president and vice president? Where would Suu Kyi be? Who is the speaker of the parliament?” he said.

The Tatmadaw seized control citing unsubstantiated allegations of election fraud by the NLD, which won by a landslide. The junta consolidated its power by removing 24 ministers and naming 11 replacements under a year-long rule under a state of emergency, Reuters reported.

Ketut said Myanmar had not been able to manage its underlying issues with the junta, because the institutional and constitutional settlement processes did not exist, and that civil society was not allowed to develop properly.

“Myanmar’s support system is in ASEAN, but ASEAN appears to be distracted by the pandemic this year,” he said.

ASEAN should offer solutions and Indonesia should be more proactive in ensuring a “soft landing” in Myanmar’s democratic transition, while offering itself as a buffer from the more antagonistic approach by the West, Dewi said.

“If Indonesia doesn’t take up the role, who else would do it? If Europe [or the United States] imposes an embargo, it is acting as the bad cop, which is necessary. But we still need Indonesia and ASEAN as the good cops who will try to reason with Myanmar,” she said.