Trying to understand gang violence

An exhibition tries to make sense a trend of random violence in Yogyakarta perpetrated by teenagers.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

Y

ogyakarta can be a comfortable city, a safe place for both visitors and residents. But like other big cities, at night, its streets can be a place of unexpected violence. At least, this has been the experience of Rafi, a 26-year-old native of the city.

"[A few months ago], I was going home by motorbike alone, around 1 o’clock in the morning, when I suddenly heard what sounded like shots and then a bang! The only thing I remember afterwards was the pain in my stomach," he recalls.

Rafi had an open wound in his left abdomen. He managed to stop his motorcycle before collapsing onto the asphalt. Although he couldn’t see clearly, he spotted two teenagers riding on motorbikes, brandishing daggers and screaming gleefully. Some people who were passing on motorbikes took him to the hospital.

The above occurrence is often referred to as klitih, a term used to describe seemingly random acts of street violence in Yogyakarta, almost always done at night. Klitih perpetrators, who are usually of high school age, conduct this violence without a clear motive. Victims rarely have anything stolen from them; the point seems only to be to inflict grave wounds. The randomness is terrifying for the victims.

"I so was traumatized that I didn't dare ride a bike at night for several years," Rafi says.

This violent phenomenon is being highlighted by Yahya Dwi Kurniawan, a 26-year-old Yogyakarta-based artist, in an exhibition titled "The Museum of Lost Space". The exhibition is an attempt to view klitih from a wider perspective, particularly its relation to gang hostilities between high school students in Yogyakarta.

A history of violence

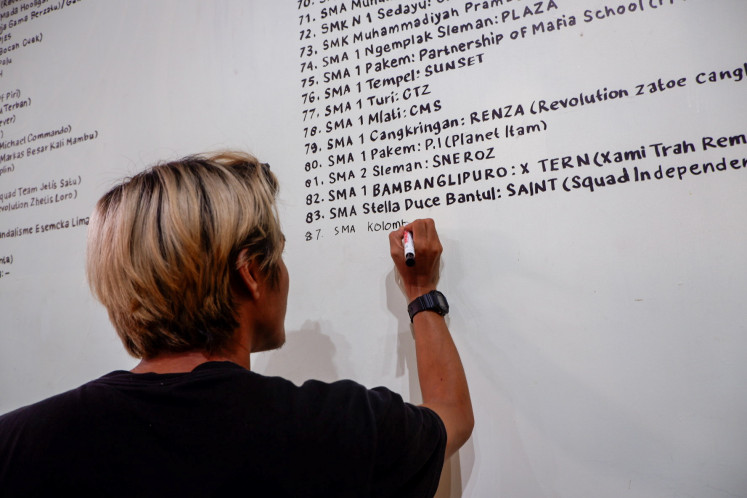

In Javanese, the term klitih previously had a more innocuous meaning: wandering at night for fresh air. The term later shifted to indicate street violence committed by high school students to prove themselves, usually to a gang they are seeking to join. Almost every high school in Yogyakarta has a gang, such as the Organization of Students Obedient in Worship (OESTAD) from SMA Muhamadiyah 1 state high school, HAMMER from SMA Pangudi Luhur, Gama Youth United (Regazt) from SMA Tiga Maret and many others. High school gangs also exist in a number of other Indonesian cities, including Jakarta.

The Yogyakartan gangs routinely maintain their prestige through brawls. Originally, klitih served as a way for them to challenge each other. "But the situation then and now are different. In the past, the victims were only students from rival high schools. The weapons were also not used to seriously harm their opponents. Now, the victim is random, and [klitih] can even be used to kill people, which is irresponsible,” said Irfan, a former member of the Great Zone Gang (BGZ) from SMA 1 Banguntapan Bantul, who came to Yahya’s exhibition.

From 2019 to 2020, 40 cases of klitih were recorded in Yogyakarta. In January of this year, five teenagers were arrested by the Yogyakarta Police for allegedly partaking in such violence. The hashtag #DIYDaruratKlitih (Yogyakarta klitih emergency) often trends on Twitter.

Complex motives

"People generally think klitih perpetrators are just teenagers who have too much free time, but we believe there are more complex reasons behind it," said Arham Rahman, the exhibition’s curator.

To grasp klitih thoroughly, the team conducted research starting in August 2020. They met 10 former klitih perpetrators. They said that at a certain level, the young klitih perpetrators were victims of complex structural violence.

"We don't [want to] enable or blame klitih, but hopefully the public can see klitih from another perspective," said Yahya.

Their study of the city’s street violence led them to two conclusions about the reasons behind klitih.

The first was a loss of space for young people to express themselves, such as parks, mostly resulting from urban development that was unfriendly to the public.

The second was the psychological background of the perpetrators. The researchers said the perpetrators had often experienced some form of violence at home or in their surroundings. The exhibition brings to the front the often threatening and violent relationship between the public and the police, who are often seen as ineffective at eliminating these issues.

"Yogyakarta is built on a tourism regime. In terms of development, the city of Yogya may appear to be growing steadily. But in reality, the social space of these young people is getting compressed to the point that it is almost gone. Many spaces that used to be accessible are now private and exclusive, both economically and socially," said Arham.

Yahya tries to present that missing space for expression in his exhibition. Apart from displaying klitih weapons, such as sickles, chainsaws, motor gear, chains and pistols, other work is exhibited in a participatory space. There is a 3 by 10 meter wall that functions as a graffiti room for anyone to spray or scribble on. Near it, empty spray paint canisters are scattered about, and slowly, the wall has become filled with scribbles, messages and gang names, just as on the streets, where high school gangs spray graffiti to mark their territory or to provoke an opposing high school.

There is also a high school distribution map along with gang names that anyone can add to. "You could say this is more like a collaborative exhibition," said Yahya, laughing.

“The Museum of Lost Space” exhibition will be held from March 6 to April 6. In addition to the exhibition, the curators are holding a theatrical performance and publishing a book based on their klitih research.

Experienced visitors

Unlike other art exhibitions, which are usually attended by art aficionados, “The Museum of Lost Space” attracts young people who have experienced klitih culture themselves, either as victims or perpetrators.

Yahya wants the exhibition to cause the perpetrators and victims reflect on their experiences.

"If my show can't reach or touch [victims of klitih], it means I'm exploiting them. I'm very careful about that," said Yahya, who has been familiar with violence since childhood. At his birthplace in the village of Wates Prontaan Magelang, he was once known as a prominent gang member.

Yahya has promoted his exhibition and cause on a Facebook group called "Geger Geden YK" which has thousands of Yogyakarta high school students as members. Delivering his messages in a language familiar to teenagers, he has succeeded in having people in or adjacent to the world of klitih listen to him and visit the exhibition.

Ferdi, 19, a visitor who did not want to use his last name, said he was interested in coming because he did not expect that the activities of his high school days could be packaged into an art exhibition. Ferdi had performed klitih in the past, but Yahya hoped the exhibition would make Ferdi understand that he was a product of a violent environment.

But Ferdi still has little regret about his past actions.

"Coming here,” he said, trying to find the words, “gives me a sense of high school nostalgia.”