Raising the bar on sexual reproductive health and rights in age of climate change

An important link between sexual reproductive health and rights and climate change is still not fully understood by many.

Change Size

T

he Asia-Pacific is at the forefront of experiencing the impacts of climate change, as it is vulnerable to floods, cyclones, earthquakes, droughts, storms and tsunamis.

Forty-five percent of the world’s natural disasters have taken place in the region in the last three decades, according to Biplabi Shreshtha, program director at the Asian Pacific Resource and Research Centre for Women.

During this period, the disasters affected more than 200 million people and killed 70,000, which represent 65 percent of the global total annually.

“The impacts of climate change-related events are not gender-neutral; women and girls are more vulnerable and disproportionately impacted due to preexisting gender inequalities,” said Shreshtha, whose nonprofit organization works with over 80 groups in 17 countries.

She said gendered impacts, especially on sexual reproductive health and rights (SRHR), included added burdens within households and girls dropping out of school to help produce energy and gather food and water for their families.

Early age marriage, she said, had been used as a coping strategy in many poor communities, while other impacts included the increase of gender-based violence within families; food insecurity and malnutrition among girls and women; and lack of access to healthcare services, especially for sexual reproductive health.

“Business as usual is inadequate to meet the challenges of today and their consequences,” Shreshtha said in her presentation at the fifth session of the 10th Asia-Pacific Conference on Sexual Reproductive Health and Rights (APCRASRH10) virtual conference on Aug. 17.

The conference, taking the theme “Climate change and SRHR in Asia and the Pacific”, is part of a series organized by the steering committee of APCRSHR10, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and Citizen News Service (CNS).

Cofounder and political advisor for Diverse Voices and Action for Equality (DIVA) in Fiji, Noelene Namboolivo, said there was an important link between SRHR and climate change, as well as between disaster risk and response and the elimination of violence against women and lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) human rights, including LGBT-related communities.

But the link, she added, was still not understood fully by many.

“In the midst of the pandemic and all natural calamities, there is a need to convince people that SRHR is central to any development response because it is the body where the damage and human rights violations are felt most,” she said.

She said women in the Pacific, for instance, had some of the highest unmet needs of contraception and there were high levels of violence against women.

“We have to highlight these issues and devise strategies and tactics that will help us create systems of safety for everyone, including women, girls and marginalized people,” Namboolivo said.

GLOBAL GOALS

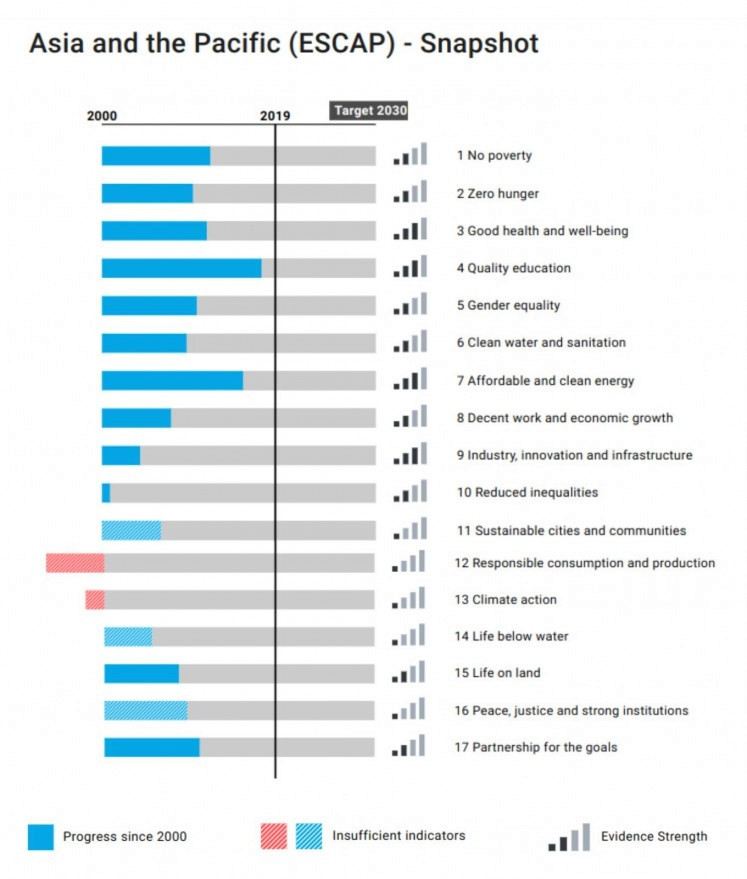

Five years ago, 193 countries, including Indonesia, unanimously adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – a set of 17 goals designed to bring the world to several life-changing “zeros”.

The goals include taking urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts, ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all at all ages and achieving gender equality and empowering all women and girls.

With just 10 years left to achieve these goals, the pandemic struck, putting many programs centered on reaching these goals in jeopardy.

Population expert Adrian Hayes said one might think SRHR on the one hand and climate change and sustainable development on the other have little to do with one another.

The fact is, he said, they are interrelated in a number of ways, such as the causal links between health and climate change.

“If many of the environmental changes brought about by climate change affect population health [usually negatively], then 'health' here will include sexual and reproductive health too. Furthermore, the causality can work in the other direction too,” he told The Jakarta Post through email interview.

“Coping well with climate change and environmental degradation requires a healthy population and resilient communities. Investing in human capital [which includes health] is an important element of building long-term sustainable development.”

Earlier, Hayes, honorary associate professor at the School of Demography at Australian National University, gave a plenary presentation at the conference.

“We cannot achieve the SDGs without resolving the looming crisis of climate change,” said Hayes in his presentation.

“Improving SRHR in the Asia-Pacific region will contribute to achieving the SDG goals and resolving anthropogenic climate change.”

He said two indicators of SRHR in countries of this region were the unmet need for family planning and the maternal mortality ratio (MMR).

“These two indicators give an objective measure of the general status of SRHR across cultures in the region and give the scale of challenge in each country,” Hayes said.

The global target is to achieve universal access to family planning services – that is, for family planning to decline to zero by 2030.

“But perhaps it might be more realistic to achieve the goal of reducing it to 10 percent instead of zero by 2030,” Hayes said.

He said estimates had shown this target had been reached by some nations of the region, including China, Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand and Vietnam.

“But other countries still have a way to go,” Hayes said.

In Southeast Asia, Singapore, Vietnam and Thailand have already reached the 10 percent threshold, while there has been a dramatic decline in Cambodia during the current century.

“Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines and Myanmar appear likely to just miss the 10 percent target by 2030, but like India, they are within striking distance,” Hayes said.

Indonesia has benefited from a successful national family planning program in the past three decades but Hayes said the recent challenges had been to broaden the range and accessibility of sexual reproductive health services, improve their quality and advance a shared understanding of them, together with an adequate means of redress for those whose rights have been abused.

According to UN Population Division publication Estimates and Projections of Family Planning Indicators 2020, although unmet needs are still on the decline in Indonesia, the rate is not fast enough to drop below 10 percent by 2030.

“To be absolutely certain of a positive outcome here, the family planning program in Indonesia would appear to need a dose of revitalization,” he said.

The second indicator, he said, was MMR and the goal was to reduce the global MMR to less than 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030. In Indonesia, however, MMR remains high at 305 per 100,000 live births as of 2018-2019.

Hayes said there was a need for new policies, new programs, new interventions, more service providers, development of new outreach programs and improved service delivery. These, in turn, require improvements in many other non-SRHR sectors, from reducing poverty to improving education for all, especially girls.

“Improving SRHR in isolation from all of these other developments cannot be an option,” Hayes said. “SRHR may appear to play a merely modest role in the SDGs, but improving SRHR is essential to realizing the vision of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.”

The vision for the future contained in the SDGs includes universal human rights, and SRHR are an integral part of this vision.

“In other words, those working to improve SRHR need to think about the SDGs, and those working to implement the SDGs need to think about SRHR. We all need a holistic approach; none of us can hope to reach our specific sectoral goals if we all work in silos,” Hayes said.

While the pandemic is an emergency, he said this did not mean forgetting medium- and long-term goals, even if it meant putting some longer term activities on hold temporarily.

“The sky will not fall down if we don't reach the SDG targets by 2030. Nevertheless, the evidence is pretty overwhelming by now that some crucial environmental thresholds have been, or are being, reached, which once passed make it very difficult to maintain the life-supporting services normally provided by the biosphere,” Hayes said.

“If SRHR are not improved by 2030 then not only are these two SDGs not going to be reached but the whole set will be weaker because they are all causally interconnected to some extent. The entire vision is compromised, since it depends on universal access to human rights and human rights are inalienable and indivisible.”