ASEAN is failing its ‘ultimate test’ in Myanmar. But it’s not too late.

Min Aung Hlaing, the junta chief, has said he plans to implement the ASEAN plan when “stability returns”, or in other words: Thank you for the meeting, now leave us alone.

Change Size

I

t was just a few weeks ago on April 24 that Southeast Asian leaders emerged from a special summit on Myanmar hailing a “breakthrough”. The military junta had signed up for a “consensus” plan, vowing to end violence against protesters and allowing ASEAN to facilitate dialogue.

Cautious hopes were raised for an end to the crisis triggered by the coup the Tatmadaw (Myanmar military) launched on Feb. 1.

Since then, Myanmar’s security forces have instead continued to wantonly kill people, arrested hundreds and launched scores of airstrikes against civilians in the borderlands. Min Aung Hlaing, the junta chief, has said he plans to implement the ASEAN plan when “stability returns”, or in other words: Thank you for the meeting, now leave us alone.

A mooted ASEAN special envoy is nowhere to be seen, nor is the purported dialogue involving the opposition. If Myanmar is the ultimate test for ASEAN’s ability to solve crises, it is one the grouping is currently failing.

There is still time to do something, however. The regional bloc can prevent more bloodshed in Myanmar and bring an end to the crisis, but it must act decisively and urgently.

There is no question that the Tatmadaw is a monstrosity that must be stopped at all costs. Since seizing power in February, security forces have killed close to 800 people as well as driven the country to the brink of economic collapse and a humanitarian disaster. But military abuses stretch back decades. I was myself recently part of the United Nations fact-finding mission that documented its atrocities against Rohingya and other ethnic minorities.

As brutal as the military is, this is not a crisis that has happened in isolation. Respect for human rights norms have been eroding in Southeast Asia for decades.

In Cambodia, Prime Minister Hun Sen has jailed or exiled the opposition and rules like a tin-pot dictator. In the Philippines, the government of Rodrigo Duterte has killed thousands in a vicious “war on drugs” while muzzling the media and critics alike. In Thailand, the quasi-military government has arrested hundreds, including more than a dozen children, who dared to join street protests calling for democracy.

All the while, ASEAN has stood idly by. Regional leaders have hidden behind a “noninterference” principle and avoided voicing any criticism. It is in this climate of impunity that the Tatmadaw felt emboldened to seize power so brazenly: They knew there would be no consequences.

It is true that the ASEAN Special Summit on April 24 was, to some extent, a positive step forward. It was the first time the bloc held an emergency session on a member state’s internal situation, and some of its members have publicly and strongly condemned the Tatmadaw, notably Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore. ASEAN officials have privately told me they feel cautiously optimistic since the summit, and what they believe pushing the boundaries of the “noninterference principle” will mean for the region’s future.

But we need action now, not in the long term. The junta’s contemptuous response has also exposed the limits of the consensus-based decision-making the regional bloc prides itself on. While ASEAN was giving Min Aung Hlaing the red carpet treatment in Jakarta, people continued to die on the streets while defending democracy in Myanmar.

The real test for ASEAN is what happens next. It is clear that this is a crisis that needs a regional solution, not least since the UN Security Council, the European Union and other key international actors have all called on ASEAN to take the lead. With the Tatmadaw thumbing its nose at the bloc, Southeast Asian leaders must put their collective foot down.

The very first step must be to appoint an ASEAN special envoy to Myanmar who has strong human rights credentials for an immediate visit to the country. The envoy should open dialogue with the National Unity Government as the legitimate government of Myanmar. This will show ASEAN’s seriousness and send a strong signal to the Tatmadaw that more bloodshed and repression is unacceptable.

ASEAN must also support what we, the Special Advisory Council for Myanmar, call the “three cuts” strategy to deal with the junta. This includes imposing sanctions on the individual architects of the coup and the businesses that sustain the military financially. A global arms embargo must be placed on Myanmar to end the military’s access to weapons. Finally, ASEAN member states should publicly support the efforts to hold the Tatmadaw accountable for its crimes, including through the International Criminal Court.

While things look bleak now, we must remember that there is nothing inevitable about military rule in Myanmar. In my own country, I saw how we went from 30 years under the repressive regime of former president Soeharto to one of the region’s most progressive democracies in the space of a few decades.

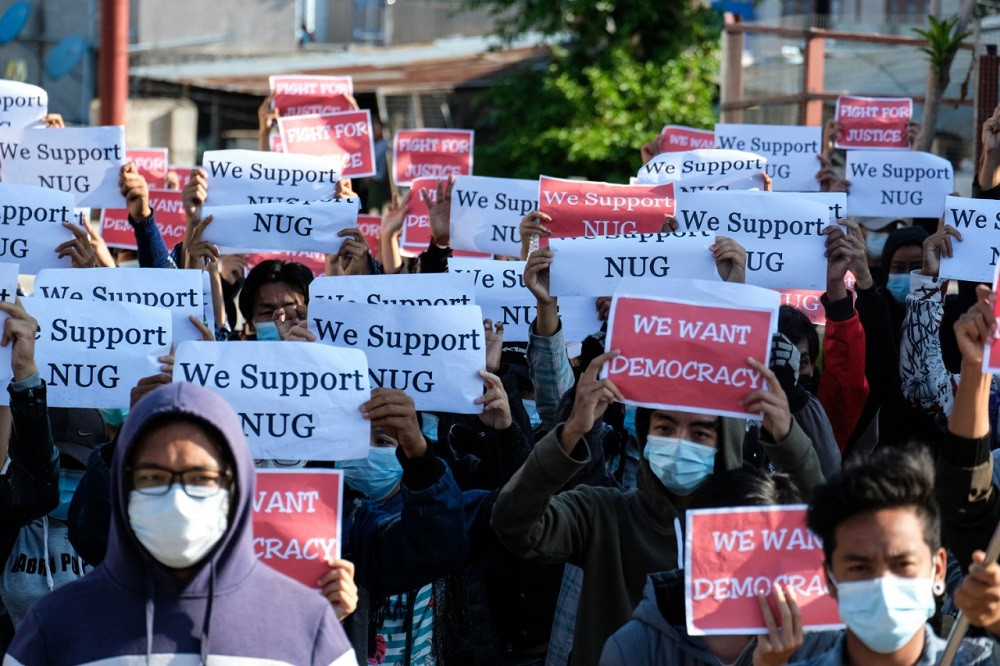

The people of Myanmar are still courageously taking to the streets to push for change. The sacrifices of those who have paid the ultimate price for democracy and human rights must not have been in vain. They need all of our support. ASEAN has no time to lose.

***

Founding member, Special Advisory Council on Myanmar