Many Indonesians’ perception of rape is limited to the traditional definition of a stranger grabbing the victim, physically restraining her, raping her and running away. Given this narrow definition, there is no justice for those women who fall victim to other types of sexual violence, and the perpetrators enjoy impunity. The House of Representatives has initiated a bill on the eradication of sexual violence, which has made it onto the National Legislation Program (Prolegnas) this year. The bill seeks to broaden the definition of sexual violence to ensure better protection for women. With this urgent matter taking center stage, The Jakarta Post’s Evi Mariani looks into forms of sexual violence that remain unclassified as crimes.

When survivor Kelly (not her real name) saw her rapist’s name in the byline of an article on the front page of a national newspaper, she asked herself how he could be a successful journalist while she could not even type, so severe were the tremors in her hands.

“How good his life is, and how miserable mine!” she wrote in her diary. In Indonesia, as in many parts of the world, victims of sexual violence often have their lives turned upside down, while perpetrators enjoy impunity.

In the US two years ago, the adopted daughter of renowned director Woody Allen, Dylan Farrow, wrote an open letter accusing her father of sexually assaulting her when she was seven.

“That he got away with what he did to me haunted me as I grew up,” she wrote. “I was stricken with guilt that I had allowed him to be near other little girls.”Allen has never been charged for the alleged crimes, and his representative insisted the claims made in Dylan’s letter were untrue.

Dylan said in her letter that she had suffered eating disorders and engaged in self-harm as a result of her traumatic childhood; Kelly, similarly, suffered post-traumatic stress disorder, resulting in tremors, sleepless nights and self-isolation. She has permanently lost her appetite and can no longer work.

Kelly said her rapist had married and had a daughter. Now, she wants him to be punished for his crime. She recently filed her case to the Legal Aid Foundation of the Indonesian Women’s Association for Justice (LBH Apik) and the National Commission on Violence Against Women (Komnas Perempuan).

Many Indonesians, however, would not consider her case to be rape. The rapist was not a stranger, the rape happened more than once and it happened three years ago.

“The first thing the police would ask her would be, ‘Why file a report now?’ The second question would be, ‘Why did you let it happen several times?’” Lidwina Inge Nurtjahyo, a lecturer at University of Indonesia’s (UI) law school and the head of the women and children’s law clinic at the university, told the Post.

The Indonesian legal system has difficulties in recognizing rape within a power relationship gained through manipulation and psychological threats. Even rape cases using physical threats can be dropped by the police on a lack of evidence and witnesses.

A sexual assault case implicating poet Sitok Srengenge against UI student RW, for example, came up against obstacles because the police demanded proof and witnesses. RW’s lawyer, Iwan Pangka, reported the case not as rape (Article 285) but as a violation of Article 335 of the Criminal Code (KUHP), which says anyone found guilty of forcing another person to do anything by means of threats of violence is subject to a maximum sentence of a year in prison.

After 11 months of investigations and public pressure, the police in October 2014 named Sitok a suspect for violating Article 335. The case has yet to see progress.

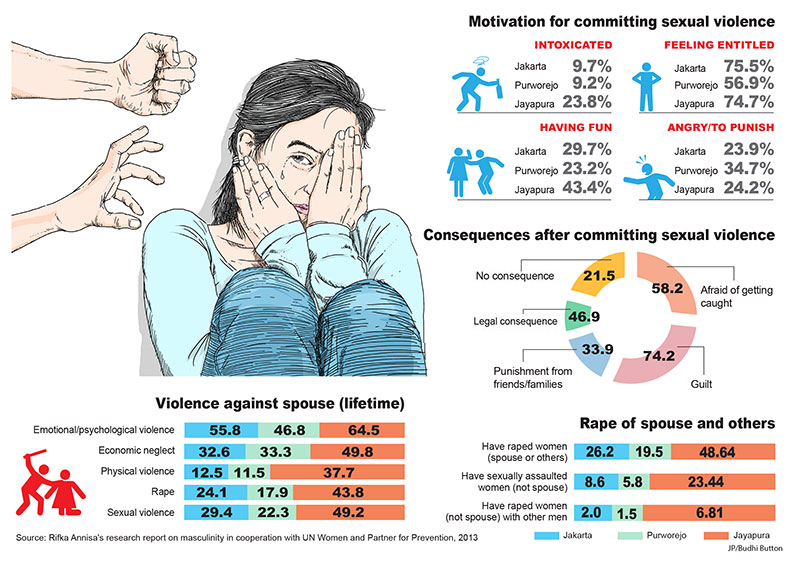

A 2012-2013 masculinity study carried out by women’s crisis center Rifka Annisa in Yogyakarta, in cooperation with UN Women and Partners for Prevention in Bangkok, revealed staggering figures of impunity and male entitlement to sexual violence.

The study was conducted in three cities: Jakarta to represent a major city, Purworejo in Central Java to represent a smaller town and Jayapura in Papua to represent eastern Indonesia.

Male surveyors interviewed 2,577 men aged between 18 and 49 about their experience of committing sexual violence; answers were entered electronically to ensure truthfulness to sensitive questions.

In Jakarta, 24.1 percent respondents said they had, in their lifetime, raped their spouse; in Purworejo the figure was 17.9 percent, while in Papua it was 43.8 percent. In Jakarta, 29.4 percent answered they had sexually assaulted their spouse, in Purworejo 22.3 percent and in Papua 49.2 percent.

When the questions broadened to rape of spouses and women other than spouses, the figures increased to 26.2 percent in Jakarta, 19.5 percent in Purworejo and 48.64 percent in Papua.

The motivations given were equally shocking: Only 9.7 percent, 9.2 percent and 23.8 percent, respectively, of respondents in Jakarta, Purworejo and Papua said they had committed rape because they were intoxicated, while 75.7 percent in Jakarta said they had done so because they felt entitled and 29.7 percent said they had wanted to “have fun”.

In total, 46.9 percent of the respondents in the three cities who had admitted to sexual violence said they had suffered no consequences for their actions, while only 21.5 percent said the consequences had been of a legal nature. Most — 74.2 percent — professed to feelings of guilt over their actions, and 58.2 percent said they were afraid of being exposed.

The figures showed that the respondents felt entitled to sexual violence and that legal repercussions were the exception rather than the rule; indeed, around a quarter did not even feel guilty about their actions.

Inge of the UI School of Law said that public perceptions about what constitutes sexual consent were too broad. “Is freezing consent? She did not say no, but she has frozen. In the US, the Supreme Court made a progressive decision, that not saying anything and not putting up a physical fight does not mean consent,” she said.

Siti Mazuma from LBH Apik, which serves as Kelly’s legal counsel, said that if Kelly had consented, as the perpetrator may have claimed, she would not have experienced bleeding. Kelly suffered recurrent anal bleeding for two years after the rape.

Inge and Mazuma agreed that proof should be allowed to take the form of psychological as well as physical scars. The legal system does officially allow for two forensics examinations: physical and psychological, but in practice, police and prosecutors are reluctant to use psychological evidence.

“Victims’ lives can never be the same again. Some of them even have to move out of their homes,” Mazuma said.

In cases in which victims have an unequal power relation with the perpetrator, they often do not even realize they have been assaulted or raped, and continue in the abusive relationship, suffering repeated sexual violence. Kelly was sexually assaulted repeatedly over a period of months, the abuse only ending once the perpetrator married another woman. It was not until some time later that a stranger she knew from Facebook told her in a chat that what had happened to her was in fact rape.

Mazuma spoke of a case in which the perpetrator had assaulted the victim more than 30 times and impregnated her; the victim gave birth, and the perpetrator refused to take responsibility. “She did not want the relationship,” she said.

Komnas Perempuan chair Azriana said the commission had worked closely with the House of Representatives to formulate the bill on the eradication of sexual violence. The bill initially listed 15 forms of sexual violence, which were later whittled down to nine.

“It was not a case of reducing [the number of forms], but of making them more compact. For example, we had ‘sexual control’ among the 15 but later we realized that [sexual control] was an element in all types of violence,” she said. Komnas also took out traditional beliefs that violate women’s bodies, such as female circumcision, believing that campaigning against such practices was better than legal action.

Azriana said the bill did not explicitly mention “power relations”, but did elaborate such relations.

The bill lists one type of sexual violence as sexual exploitation in which perpetrators bait victims with lies, persuasion, promises to marry the victim and conditioning the victim to be in a subordinate position. In such circumstances, despite the apparent giving of consent, the lies or coercion constitute a form of sexual violence, according to the bill.

The bill also aims to ensure victims receive restitutions, ranging from physical and psychological therapy to pecuniary compensation.

“President Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo is particularly concerned with restitutions and healing for victims in the bill,” Azriana said.

Last month, Women’s Empowerment and Child Protection Minister Yohana Susana Yembise said the bill, which has been included in the 2016 Prolegnas, was desperately needed to tackle the growing number of cases of sexual violence against women and children.

“The House will deliberate the bill this year and it will certainly be a tough deliberation. This is something people have considered normal for a very long time, so debunking it, changing the paradigm, will be a major challenge,” Azriana said.

Loud and clear: Women and men come together in a rally protesting sexual violence against women in Jakarta, calling on the government to ensure proper punishment of the perpetrators of sexual violence. Half-hearted prosecution of sexual abusers and a masculine-oriented culture have failed to protect many women and created impunity. (Antara/Akbar Nugroho Gumay)

Loud and clear: Women and men come together in a rally protesting sexual violence against women in Jakarta, calling on the government to ensure proper punishment of the perpetrators of sexual violence. Half-hearted prosecution of sexual abusers and a masculine-oriented culture have failed to protect many women and created impunity. (Antara/Akbar Nugroho Gumay)

Survivor wants rapist brought to justice to get life back

She is a survivor, that much is clear to me. She is sad, angry and depressed. She hears voices telling her to “end it all”, but Kelly, not her real name, continues to survive. Her life is clouded with sadness. She writes to help herself heal. In a South Jakarta shopping center, she pens her feelings in a notebook. She writes in English, the grammar not perfect, but intelligibly, setting out her story clearly. She decided to send parts of her diary to The Jakarta Post; luckily, she had friends to help her type, as her own hands tremble too severely to be able to do so herself. Her friends helped her edit the English too. Following are excerpts from Kelly’s diary, further edited by the Post, with her approval:

It was three years ago and I still feel the pain every single day. I have gone through many things to be where I am right now. Countless tears, bleeding, sleepless nights; I’ve had enough.

Today, I want to take my life back.

I was 23 years old, a naive and cheerful girl in a hijab. I read philosophy books. I was a passionate defender of minority rights and human rights. I even helped people extract themselves from abusive relationships.

And then he came along. He was smart and charming and seemed to believe in gender equality. He was a journalist who shared my passion for literature and philosophy.

I thought I had found an intellectual friend; until one day, everything fell apart. My life would never be the same again.

He raped me. He touched me without my consent. I was shocked and frozen. He was not even my boyfriend.

I told him it hurt.

He said, “I did it because you are smart and pretty and I adore you.” He used sweet words to calm me and prevent me from resisting, even though I knew I did not want it.

I screamed in pain but he didn’t care. He said my scream was sexy and my expression was cute.

His violence, sweet words combined with degrading words as if I was an object, made me feel inferior and confused. I was in his control; I was in a game where he set the rules.

The game left me with no self-confidence. And the game went on for some time. I didn’t know what it was. Was it dating? Was he my boyfriend? But he kept me from treating him like a boyfriend on social media. It was a secret and he wanted me to keep it a secret too.

Once he said he was serious about me and wanted to marry me, and on another occasion he said he wanted to meet my father.

Ignoring the pain I carried in my body, I kept telling myself that he was a good person and that it was a real relationship.

It turned out while he was with me he was already engaged to someone else.

A month later he got married; meanwhile, I was suffering from recurrent anal bleeding.

A year later, a friend asked me why I hadn’t reported the violence to the police. I didn’t tell anyone about the traumatic experience for months. I didn’t even know it was rape.

There were times I couldn’t even get out of bed. I didn’t attend classes, and I couldn’t even work to support my own life.

One day, I was chatting with a stranger on Facebook. I told the stranger about what had happened to me. He said it was rape. I was confused.

How would I defend myself? I knew the system, I knew I would be blamed. Even before they could lay the blame on me, I had blamed myself thousands of times.

And then I met another man. I thought he was my guardian angel who would protect me. He calmed me when I had my nightmares. He knew my rapist very well. They were friends.

I told him his friend had raped me and he said that I was not the only victim. He cried for me.

He was not just my guardian angel, caring and sweet and kind. He understood gender equality. We talked about the relationship between Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, and said he would not become a “player” like Sartre. It was not fair on the women Sartre had slept with, he said. I believed him.

Two years later I found out that he had initiated similar relationships with a friend of mine and another woman, and had even exerted physical force against my friend.

He provided a comforting shoulder to cry on for vulnerable women who came to him and persuaded them to have sex with him.

Nine types of sexual violence listed in bill

- Sexual harassment including verbal harassment

- Sexual exploitation

- Forced use of contraception

- Rape

- Forced marriage

- Forced abortion

- Forced prostitution

- Sexual slavery

- Torture using sexual abuse

I think he himself did not realize that it was wrong. He was a sexual manipulator and he didn’t know it.

I felt so stupid but I also sympathized with my friend, who began to suffer depression. I had felt all the symptoms she was suffering. He had known our weaknesses, our fragility, and yet he used us.

I confronted him for what he had done to us. My post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) had been exacerbated by the fresh revelations, but he was busy trying to save his reputation. He tried to make sure we wouldn’t talk.

I had already blamed myself for what had happened three years ago, but this just made things even worse.

I am angry with my psychologists, my parents, my religion. I grow angry when people say, “Everything happens for a reason.” No one deserves to be raped. I have insomnia, and when I do manage to drift off, nightmares strike; I wake up crying.

A couple of months ago I began to stay in bed all day without eating. My appetite is gone. I spend my days crying in bed. I like to write and I have a blog with many followers, but each time I tried to write, my mind drew a blank.

One day I realized that to overcome my trauma, I had to confront my past. My rapist is married and now has a daughter. He even said he would fix himself and that I would be his last victim. If marriage could fix a rapist, how about justice for the victims and the burden they have to carry in their bodies and their souls?

When I saw his name in a byline on the front page of the newspaper he works for, I thought, “How good his life is, and how miserable mine!”

He could write about important things happening in the country and I couldn’t even write a blog post because my hands were shaking so much, a result of my PTSD.

My psychologist said it was because my feet were in two different times: one in the past, one in the future. The past terrifies me, the future makes me anxious. My therapy now is to focus on the present day.

I look at myself in the mirror, but I don’t see my own body. All I can see are my wounds, all I can feel is pain.

Every day I have to fight the voice in my head that tells me to end it. “End it, end it.”

But I’ve found the courage to open up. I have spoken out to my friends and my sister. My sister said, “You know the law and human rights, and if you keep silent, how about those women who don’t have your awareness and your access?”

Many friends have reached out. I believe that by speaking out, I can help others.

I am searching for my faith again, trying to rebuild the values I lost. I am still receiving treatment for my trauma, but am growing stronger.

I am ready to fight this battle.

This article was first published in The Jakarta Post paper edition on July 19, 2016.

| Editor-in-Chief | : | Endy M. Bayuni |

| Managing Editor | : | Rendi A. Witular |

| Desk Editor | : | Pandaya |

| Writer | : | Evi Mariani |

| Technology | : | Muhamad Zarkasih, Muhammad Kurnia |

| Infographic | : | Budhi Button |

| Photographer | : | ANTARA FOTO/Rosa Panggabean, Akbar Nugroho Gumay |