As one of the world's largest producers and exporters, Indonesia lives and breathes coal. About 67.2 percent of its power sector came from this dirty fuel in 2022, emitting millions of tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2), having an adverse impact on people’s lives and livelihoods due to many factors, including deteriorating air quality.

At 43 percent, the power sector is the largest contributor of CO2 emissions in Southeast Asia’s largest economy, followed by the transportation and industrial sectors at 25 percent and 23 percent, respectively, according to a report by Climate Transparency published in 2022.

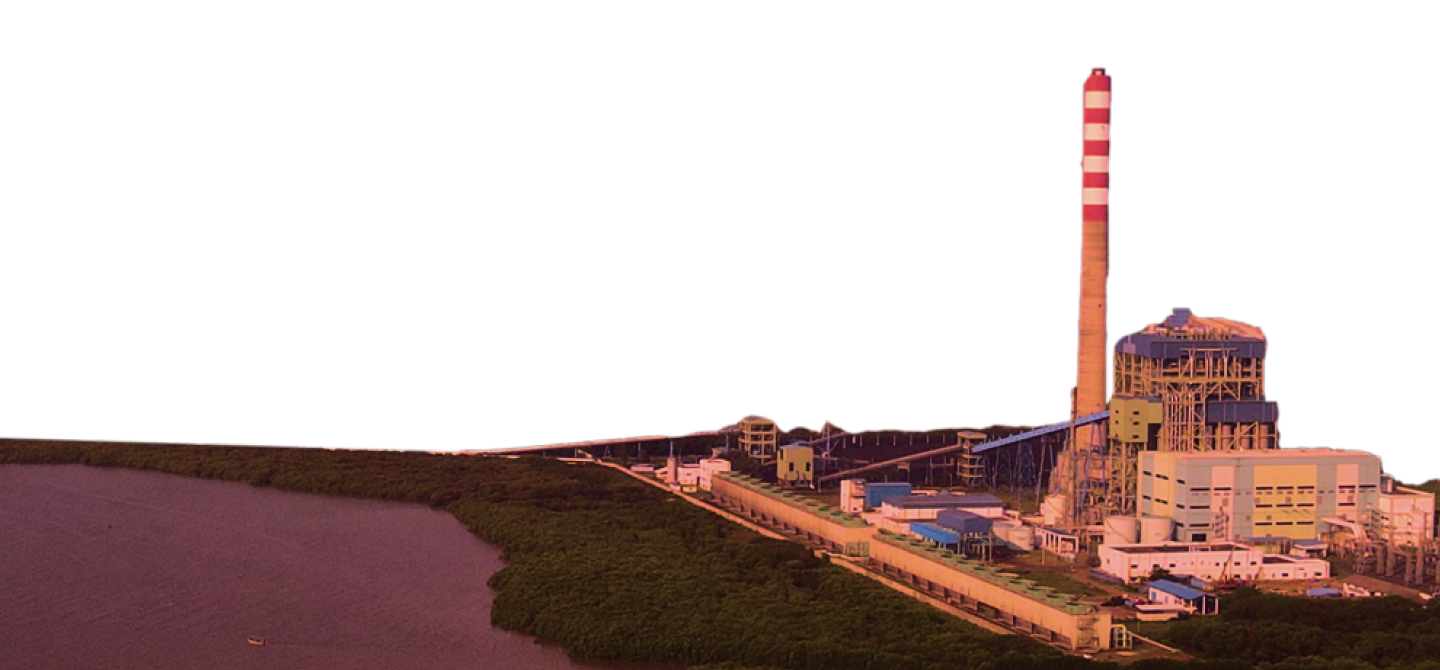

In Cirebon regency, West Java, a handful of quiet coastal villages have had their lives affected by the operations of the Cirebon 1 coal-fired power plant (PLTU Cirebon), which has altered their farmland and fishing grounds.

For more than a decade, residents, who are mostly fisherfolk and farmers, have complained about reduced income and lost livelihoods due to the power plant’s activities and waste that have led to decreases in fish catches and land productivity.

While often less observable by residents of nearby villages, studies have found that ash and other pollutants from the power plant have caused respiratory problems.

As part of its commitment to the global climate fight, the government has announced that it will retire some of its coal-fired power stations soon, including the Cirebon plant. But financing difficulties have emerged, since some of the power plants considered for retirement are still relatively young, making it expensive to pay for their closure.

At first glance, nothing was out of ordinary in Kanci village, a fishing community located in Astanajapura district on the coast of Cirebon, West Java. The streets were quiet during the day as not many villagers travel by private vehicles. At the Selo Pengantin fish market in Mundu Bay, where dozens of boats were docked, things were busier.

It was late in May when The Jakarta Post visited the village. The peak of the high season for the fishermen in the area, usually in February, had already passed.

A few boats sailed back into the bay while other fishermen were busy tending to their nets. In the horizon was the tall chimney of Cirebon 1 power plant emitting smoke, something that residents in the village have been used to for the past 10 years.

Under satellite lens, things were less than ordinary, indeed alarming. Satellite imagery observed by several researchers showed that the color of the atmosphere surrounding the power plant was deep red – indicating a high concentration of pollutants around the area.

A study conducted by Finland-based Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) in 2022 found that the Cirebon 1 coal-fired power plant dispersed toxic pollutants into the air, including nitrogen dioxide (NO2), sulfur dioxide (SO2), mercury, lead, arsenic, cadmium and fine particulate matter, or PM2.5.

Priandana, 53, has spent 30 years relying on the seas off Kanci for his livelihood, as his father, also a fisherman, had done before him.

Although he acknowledges that lives in the village have rapidly changed since the construction of the power station, he is not aware that the air in the area is polluted.

“I suppose there are health impacts caused by the waste from the operation of the coal plant, but I wouldn’t know for sure. I’m just a small fisherman, me and my family [...] we don’t go to the doctor for check-ups periodically,” he said.

“When I look around, I don’t see any visible pollution in the water or in the air either. Most people have also gotten used to living with the power plant so close to us. What is there left for us to do?”

Operated by PT Cirebon Electric Power, the Cirebon 1 is a 660-megawatt power plant that sits on Mundu Bay and overlooks the Java Sea, some 220 kilometers from Jakarta.

Priandana said he and other fishermen he met have learned to live alongside the US$850-million facility, which has faced perusal from local stakeholders since its construction began in 2008.

Responsibank, a coalition of civil society organizations, has made allegations of “gross negligence” that have caused serious environmental damage since its operations began in 2012.

Cirebon these days has grievous air quality. According to the Air Quality Index (AQI) data, the daily exposure to PM2.5 on Aug. 16 stood at 24 µg/m3, which exceeds the World Health Organization’s recommended daily guideline of 15 µg/m3.

Potential effects related to long-term exposure to the pollution include reduction in lung function in children and adults, increase rates of chronic bronchitis, increased lung cancer mortality and an increase in cardiopulmonary mortality, according to a study published in the National Library of Medicine.

Pollution emitted by the Cirebon 1 coal-fired power plant does not only affect residents living in the regency but also those in cities as far away as Jakarta.

Another research by the CREA found that pollution from coal power plants within a 100 kilometer radius of the capital city are responsible for about 2,500 air pollution-related premature deaths per year in Jakarta, costing Rp 5.1 trillion (US$334.8 million) per year.

The cause of the poor air quality can be attributed to a range of factors, from transportation to residential emissions. But the emissions from the power plant operations are also too hard to ignore.

Jakarta-based research group Prakarsa conducted in April a study to observe the health, economic and environmental impacts of the power plant on Mundu and Astanajapura, two districts located the nearest to the power facility.

From 2019 to 2022, respiratory diseases (ISPA) and tuberculosis were among the top-10 diseases suffered by the people in Mundu, home to more than 80,000 people, according to public health center (Puskesmas) data gathered by Prakarsa.

In 2019, over 1,600 people suffered from respiratory diseases and tuberculosis. The number declined in the following year as fewer people came to the health center due to the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to only a total of 700 people being recorded sick with the same conditions in 2022.

Prakarsa also found residents with long-lasting coughs and children with lung diseases.

Ricko Nurmansyah, a program research assistant at Prakarsa that participated in the study, said that ash in the atmosphere is a serious problem in the area, which affects not only people’s health, but also reduces land productivity.

“We take satellite images to observe changes in land use, air pollutants like CO2, SO2 and NO2. We also found rising temperatures in the area after the power plant construction,” he told the Post.

Air pollution caused by the burning of fossil fuels from the Cirebon 1 coal power plant was estimated to be responsible for around 440 deaths in 2022 or roughly 11 percent of an average of 4,130 annual deaths over a three-year period, CREA research has found.

“The results are astounding, but we are discovering more and more about the impact of this pollution,” Lauri Myllyvirta, a lead analyst at CREA and the research co-author, said in an interview with the Post.

The think tank conducted the societal and environmental impact survey of 144 coal-fired power plants in Indonesia, including the Cirebon 1 power plant, to examine the effect on health of local communities.

“In Indonesia, air pollution is caused by many things, but coal-fired plants are the easiest to address. It should be mandatory to strictly monitor emissions from these power plants individually. However, we notice that the Indonesian emission standards for coal-fired power plants are relatively weak compared with other countries, both developed and emerging economies,” Myllyvirta said.

The regulation of emissions from coal-fired power plants is set out in the Environment and Forestry Ministerial Regulation No. 21/2008, which is a revised version of the 1995 regulation on emission standards for thermal power plants. But it is still weak, according to CREA, because of two reasons: First, this regulation only covers NOx–referring to NO2 and NO, SO2, and PM. The latter does not include PM2.5, the most hazardous emissions pollutant.

Secondly, the new regulation still retains the loose 1995 standards for existing plants and for plants which were under construction before December 2008. Power plants planned at that time are subject to the 1995 standards while in transition, and have been required to comply with the new standard since January 2015. “But this is also poorly monitored,” said Myllyvirta.

CREA estimates that Cirebon 1 emits approximately 90 kilograms of mercury into the atmosphere annually.

“Out of the emitted mercury, approximately a third is deposited onto land ecosystems and a third into the ocean in the region, with the rest carried far away from the source. So this is approximately 30 kilograms falling onto land ecosystems, especially cropland, from Cirebon 1,” Myllyvirta said.

Joseph Pangalila, the vice president of PT Cirebon Electric Power (CEP), rejected claims that the coal plant has caused air pollution in Cirebon and Jakarta, saying that the company has complied with all environmental standards set by the environment ministry.

He said that the coal plant’s daily mercury emission quantity is considered low, amounting to only 0.0051 milligrams per cubic meter of air (mg/m3) compared to the government’s threshold of 0.03 mg/m3 as per the 2008 environment ministry regulation.

“We are monitoring the mercury [emission quantity]. That’s very insignificant, far below the enforced standard. Mercury and other emissions will always be there, but [the question is], how significant is [the impact]?” he said in an interview with the Post on July 10. “But there has to be a limit. In our case, the mercury level [emitted into the environment] is very low.”

CEP environmental engineer Agik Dwika said that poor air quality was a result of many factors like trash piles in landfills and burning of waste that also affect groundwater quality. He added that outdated boat engines used by some fishermen could also pollute the environment.

“Our monitoring indicates that while air pollution does affect health, it does not originate from our plant," he insisted.

The company also recorded that the coal plant’s average PM level between January and August of this year stood at 14.1 milligrams per cubic nanometer (mg/Nm3), lower than the local standard of 100 mg/Nm3 and the International Financial Corporation (IFC) standard of 50 mg/Nm3. It also said the reporting of lead, arsenic and cadmium levels was not required by either local or international environmental standards.

The Indonesian Forum for the Environment (Walhi) has documented that about 3,000 farmers and fisherfolk in the village of Kanci and another five neighboring coastal villages have had their livelihoods disrupted by the power station.

The loss of livelihood has occurred slowly across the years. Fewer boats and fishermen remain in the villages. Salt farmers, who had experienced major loss of lands when the Cirebon plant was constructed on the salt farms in the bay, faced further declines in production due to La Nina weather phenomenon over three years.

Priandana said that previously around 100 fishermen crowded the Selo Pengantin market during the fishing season, but the number of fishermen had declined significantly to only dozens these days.

Farmers work on salt evaporation ponds in Kanci village, Astanajapura (left). A fishing boat travels through a harbor in Citemu village, on May 23 (below).

“The water [in the bay] became murky and warmer after the power plant started operating, pushing fish further away from the coast,” he told the Post, saying that the majority of fishermen chose to change jobs as a result of diminished fish catches around the coast.

He said now fishermen have to go further out to the sea to catch fish, but not every fisherman has adequate equipment and resources to pay their crews to make the longer trips.

Mohamad Taufik, 57, a salt farmer, said production had declined in the past three years as the long rainy season had led to only one productive month in a year, it took longer for the saltwater to dry.

“Ash from the coal plant also affects the salt quality. When [the crystalized salt] is washed, it shows, since the ash doesn't dissolve,” he said.

Meanwhile, Prakarsa’s Ricko said he met a rice farmer who experienced a decline in production because ash from the coal plant fell on rice crops. A lower water intake for irrigation has also been reported.

“The farmer experienced a reduced crop size–from 30 sacks of unhusked rice [prior to the coal plant operation], each weighing 50 kilograms, now, he can only get five to seven sacks,” said Ricko.

A study from the Indonesian Center For Environmental Law (ICEL) found that 91 percent of coal power plants in Indonesia were located in coastal areas in 2018, raising water temperatures and causing biodiversity loss due to waste released into the seas.

Greenpeace climate and energy team leader Didit Wicaksono said most power plants are located in coastal areas because they need a large amount of water for cooling during their operation. The water released into the sea is of a higher temperature than that in the natural water body.

“Coal plants usually release the cooling water at 40 degrees Celsius. This causes changes in ambient water temperature in the coastal area, disrupting the ecosystem,” he said.

The Cirebon coal plant operation, he said, caused declines in fish populations in the coastal water, especially shrimp.

Didit also said airborne and sedimentary ash caused serious problems for residents near coal plants. Greenpeace studies on coal plants in Cilacap and Jepara in Central Java found that 80 percent of residents near the power station in each area suffered from respiratory-related illnesses.

CEP operations manager John Earl Sembel disputed the claims that the plant’s coal dust has contributed to the environmental degradation felt by residents.

For environmental control and residue management, he said the company has planted seven layers of Acacia trees, employed windbreakers, sweeper and vacuum trucks, and utilizes dust-suppression methods to capture and contain coal dust.

John said fly ash and bottom ash, byproducts of coal combustion, are collected using electrostatic precipitators and stored in a silo before being transported via capsule trucks to a concrete company for use in concrete production.

“No fly ash or bottom ash is stored outdoors,” John emphasized. “All such residues are sent to the cement company.”

The tale of the Cirebon power plant is an epitome of the coal situation in Indonesia.

At almost 11 years old, the Cirebon power plant is relatively young, just like most coal plants in Indonesia, which have an average age of 12-13 years, according to data from the Institute for Essential Services and Reform (IESR).

This is lower than the average age of coal plants in other countries like Japan and South Korea (21 years), South Africa (30 years), and Russia and the United States (41 years).

The relatively young age of Indonesian coal-fired power plants, of which there are 415, is because many new coal plants came online in recent years as a part of President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s flagship program of adding 35 GW to the national grid.

Coal is the main source of energy in Indonesia, which has one of the largest coal reserves in the world, as the government considers it the quickest means to provide cheap electricity to its people.

The new coal plants have increased Indonesia’s coal capacity by 60 percent to 40.6 GW in 2022 from 25.4 GW in 2015, when the 35 GW program was announced.

Experts consider the planned early retirement of the Cirebon power plant to be a litmus test for Indonesia’s energy-transition model (ETM).

According to a recent report by the Global Energy Monitor (GEM), which uses publicly available data on company plans, Indonesia had 18.8 GW of coal-fired power plants under construction by the end of 2022.

The young age of the coal power plants in Indonesia makes it more difficult and costly to retire them, especially the newer ones.

The Institute for Essential Services Reform (IESR) reported that 80 percent of the coal produced is exported, while the remainder is used for domestic consumption. The electricity sector absorbs 85.5 percent of domestic coal consumption, while the cement sector consumes around 12.4 percent.

This amount exceeds all other countries except China and India. It is also nearly half of Indonesia’s current coal capacity, which stands at 40.6 GW.

Cirebon Electric Power’s Joseph said that the plant used supercritical technology, including a boiler with low-NO2 burners, which increases cycle efficiency, reduces coal consumption and air pollution even though low-calorie coal is used.

The low-NO2 burners use a two-step combustion process. The fuel and air is first premixed then burns on a lower flame, reducing the NO2 by improving heat efficiency.

“We always monitor the emission real-time. Both the Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry and the Environment and Forestry Ministry can access the document, and there have not been any problems on that front,” he told the Post.

Joseph emphasized the company’s proactive stance on environmental concerns by the fact that it was the first supercritical coal-fired power plant in the country and being supercritical had been integrated into the plant since its inception back in 2006.

“Our records show that [emissions] remain below the thresholds,” Joseph argued. “If Cirebon [regency] is not polluted, how could [Cirebon 1] possibly affect Jakarta’s air quality?”

The Cirebon 1 coal plant supplies over 18 terawatt-hour (TWh) or 0.17 TW annually to state electricity company PLN’s grid. The figure is estimated to have electrified around 15.5 million houses in the last 10 years.

Economic losses as a result of air pollution, which were calculated using CREA’s health impact assessment framework, point to a staggering $400 million lost per year due to work absence and a multitude of diseases, including strokes, respiratory and cardiovascular diseases.

The story of Cirebon presents a real-world scenario in Indonesia’s coal phase-out plan. But a positive development appears as the Cirebon 1 operator signed a deal with the Asian Development Bank (ADB) in November last year to discuss a potential decommission of the facility around 15 years ahead of its operational lifespan.

The negotiation process, according to an ADB spokesperson, was in the due-diligence process as of the third quarter this year.

ADB officials revealed that the 660-megawatt Cirebon 1 power plant would be refinanced in a $250 million to $300 million deal on condition that it be taken out of service 10 to 15 years before the end of its 40- to 50-year useful life under a memorandum of understanding.

The funding platform will pool funds from private banks, philanthropists, multilateral organizations and the Group of Seven countries, among other sources, to acquire and then retire coal plants early.

Despite being seen as an impetus to Indonesia’s attempt to transition away from coal, the first-of-its-kind scheme has been marred by challenges, including those related to complex financing structures.

“The concepts and the processes of ETM, just transition, and managed coal phase-out are still at an early stage of development. By leading this pilot ETM project, ADB has initiated engagements with a broad range of stakeholders and necessary analyses that will further this pilot transaction but also help refine these broader concepts,” an ADB spokesperson told the Post.

Cirebon Electric Power is a multinational consortium of Japanese trading company Marubeni Corporation, Indonesian coal miner Indika Energy, as well as Korean firms Korea Midland Power and Samtan Corporation.

It is funded by several international financial institutions, including Japan-based Bank of International Cooperation, Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation, Mizuho Financial Group and MUFG Bank, as well as the Export-Import (Exim) Bank of Korea and ING Group.

Cirebon Power’s Joseph said that the company is still in the middle of a due diligence process. “We are negotiating with ADB and the Indonesia Investment Authority [INA]. If everything goes as planned, maybe we can reach the agreement by the end of this year,” he said.

Azis Armand, vice president director of Indika Energy, explained that there are many stakeholders involved in the negotiation, including a commitment to PLN on the power purchase agreement (PPA). Indika Energy in particular wants to secure their investment return.

“There’s financing there. There’s the Korean Exim and [other] commercial banks and then there are the equity holders. We invest [in the project] so there is expected return from the investment. This is among the things that we need to discuss together,” he told the Post in February.

The ADB spokesperson said that Cirebon 1 was chosen for several reasons. The first being, it has the “right” combination of an interested owner, a middle-aged plant and a financial structure suitable for financing. Secondly, the project’s operator, Cirebon Electric Power, has in place an adequate corporate social responsibility program.

“[The plant operator] is engaged with the community and therefore suitable to ensure the coal plant will be retired with a strong just transition consideration. While each ETM transaction will have specific characteristics, ADB believes this is a great model case that can be replicated with other independent power producers,” the spokesperson told the Post.

Fabby Tumiwa, the IESR executive director, said electricity network stability, economics, availability of alternative energy sources and social-economic conditions surrounding the facility are factors that need to be considered in choosing priority coal plants.

“The last parameter is used to calculate the economic loss that could be prevented by cutting a coal plant’s lifespan shorter compared with the compensation required to make it happen,” he told the Post, adding that it would be cheaper to retire coal plants that are over 20 years old because such old facilities require considerable upkeep costs to maintain operational efficiency.

Cirebon 1 coal power was not listed among the coal-fired power plants recommended by IESR for early retirement in 2023.

The think tank recommended early retirement of a total of 86 coal-fired power plants, which belong to independent power producers (IPP), PLN and industries, or captive power units.

Among the list are 12 coal power plants recommended for early retirement as soon as this year, including the 33-year-old Suralaya Units I-IV in Banten, 24-year-old Paiton in East Java and 28-year-old Ombilin in West Sumatra.

“Some coal plants need to be retired early because they are old and have reached the end of their economic life,” the report reads. “Other coal-fired power plants have a bad record because they are located near residential areas.”

Editor’s note: This article has been updated to accommodate PT Cirebon Electric Power’s right to reply, which emphasizes that the company complies with all environmental standards and rejects the claim that it is responsible for air pollution in Cirebon and Jakarta.

This story was facilitated by funding from the Thomson Reuters Foundation in line with its commitment to advance media freedom, foster more inclusive economies, and promote human rights through its unique services; news, media development, free legal assistance and convening initiatives. However the content of this story is not associated with the Thomson Reuters Foundation, Thomson Reuters, Reuters or any of its affiliates. The Thomson Reuters Foundation is an independent charity registered in the UK and US and is a separate legal entity from Thomson Reuters and Reuters.