Legacy, landscapes and lives: The tales of Nusantara

Dio Suhenda

Jan 8, 2024

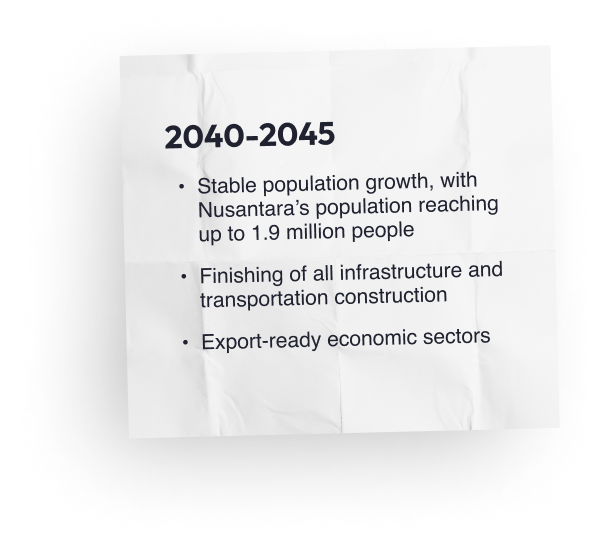

The Nusantara Capital City

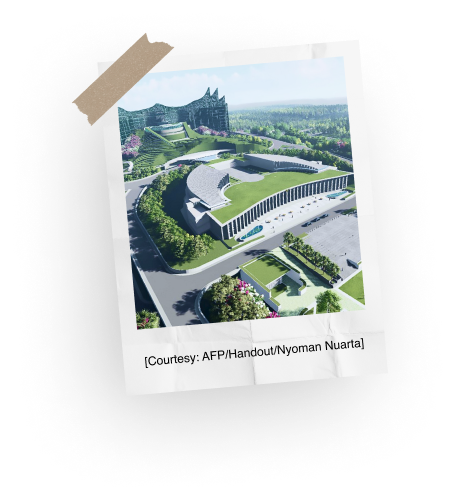

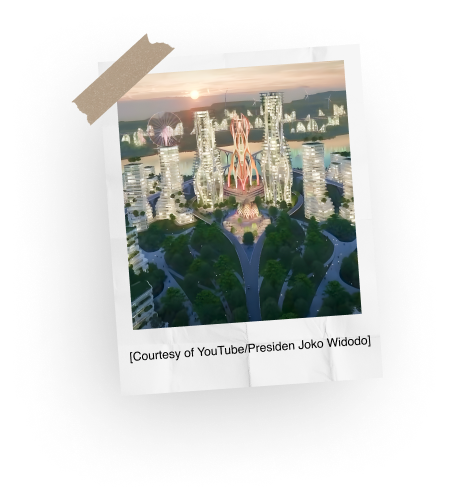

The new city will be the largest legacy of President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, who aims to bow out of his second and final term in October 2024 from a brand-spanking new presidential palace. Amid steel tracery that emulates the wings of the mythical bird Garuda, the nation’s symbol, the palace will stand firm on a hill deep in the rainforests of East Kalimantan.

Nusantara is designed to be a sprawling forest city dotted with state-of-the-art structures and infrastructure. The city is expected to champion public transportation and walkability, fitted with technology straight out of a science fiction novel, such as automated electric buses and flying cars.

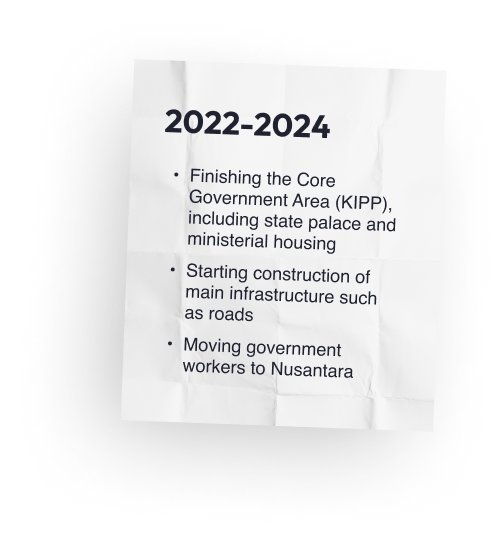

The Jokowi administration is aiming for Aug. 17, 2024, when the nation celebrates its 79th Independence Day, as the official start of relocating the Indonesian capital away from Jakarta, a nearly 500-year-old sinking metropolis notorious for its perennial pollution and traffic problems.

By then, construction is expected to be complete on Nusantara’s Central Government Area (KIPP), the administrative heart of the new capital consisting of the presidential palace, the coordinating ministers’ offices and other key government buildings and housing facilities, ready to welcome thousands of government workers transmigrating from Jakarta.

The KIPP complex, spanning 6,600 hectares or the equivalent of eight soccer fields, is only a fraction of Nusantara’s total area of 256,000 ha, roughly four times the size of the old capital.

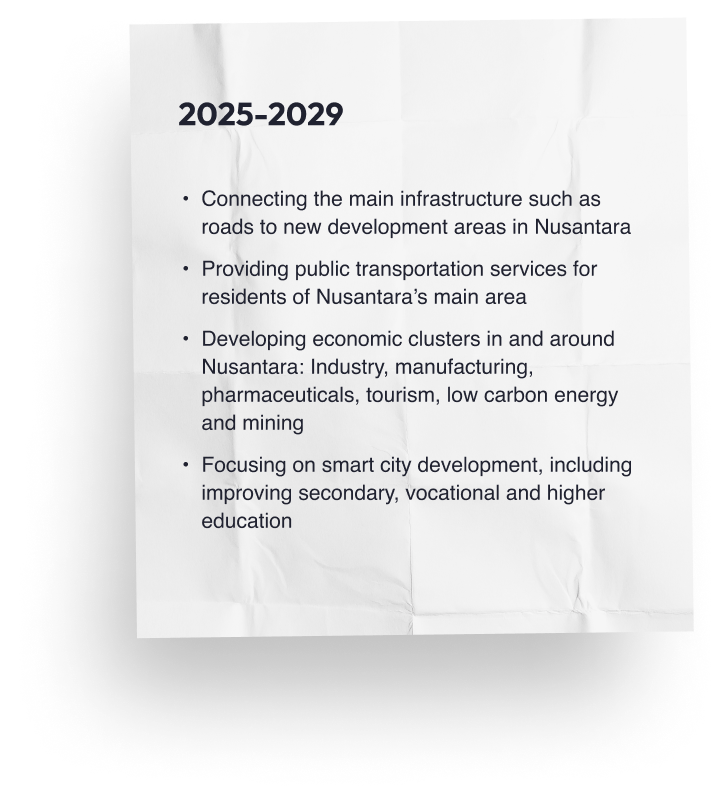

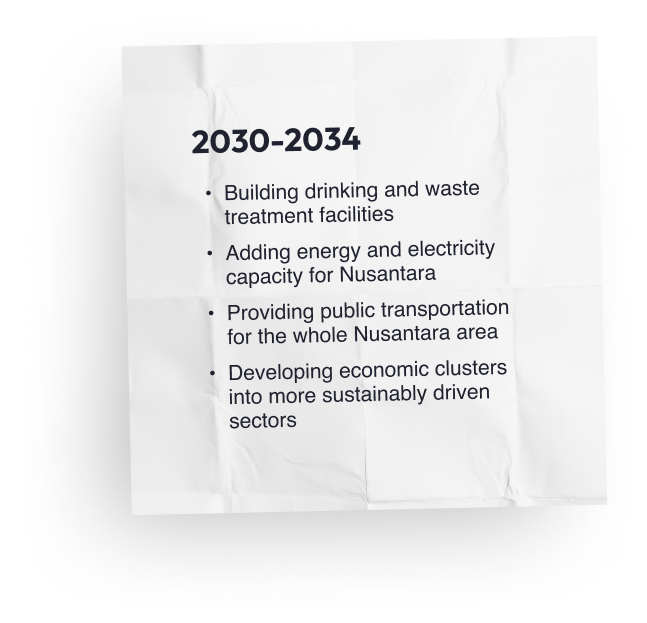

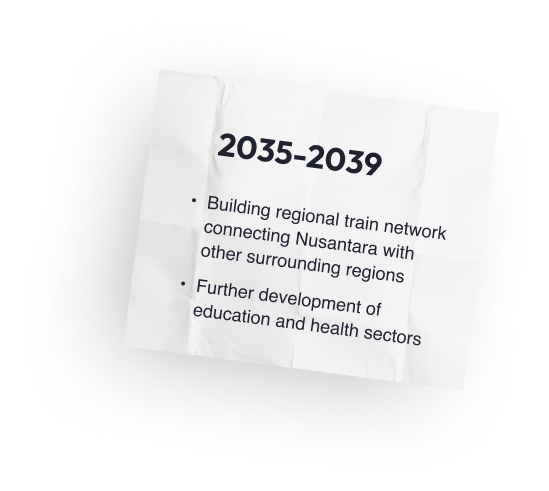

Building a city as ambitious as Nusantara will cost the state nearly Rp 541 trillion (US$35 billion), divided across several stages of development through to 2045, the centenary of Indonesian independence.

Not wanting to fan concerns that Nusantara represents a huge and misguided prioritization of state spending, the government has limited funding from the state coffers to just 20 percent of the project, putting the lion’s share of financing the city’s construction on investors’ shoulders.

Building a megacity from scratch has taken its toll on the lives of the native Balik people that used to call the newly cut forests and dammed rivers their home. The indigenous community, residing around a 30-minute drive from the site of the new capital, is starting to lose their traditional ways of life and fearing for the ownership of their land.

While his predecessors had often discussed moving the capital out of Jakarta, Jokowi is on track to be the first Indonesian president to realize the idea, despite persistent questions about the project’s feasibility and urgency, as well as the environmental damage it might cause.

Here is the story about how the 256,000-ha future city is to become the symbol of Indonesia’s development during the Jokowi era, bringing with it not only hopes for better lives but also concerns that the new capital will adversely impact the centuries-old traditions of local residents.