While the government is pressing the pedal to the metal to make Indonesia one of the world’s electric vehicle (EV) hubs, early adopters in the archipelago are having a bumpy ride amid patchy charging facilities and doubts over the technology’s sustainability in a coal-dependent country.

Arwani Hidayat has had a great time driving an EV around Jakarta for the past two years, but the ride becomes less smooth once he leaves the capital.

“It has become increasingly easy to find charging stations in the Greater Jakarta area. Driving to other provinces, on the other hand, is still a little bit more challenging,” Arwani, who has been driving an EV since 2021, told The Jakarta Post.

Arwani, who works as a special staff member at the House of Representatives, once put the car to test by driving 1,113 kilometers to Bali. He said the ride was made possible only by staying overnight at three different cities.

As one of the largest economies in Southeast Asia and a major carbon emitter, Indonesia has been at the center of global efforts to reduce emissions. The 2021 Climate Transparency Report recorded that fuel combustion is the largest driver of the country’s overall CO2 emissions, which comes from electricity (35 percent), industries (27 percent) and transportation (27 percent).

The World Economic Forum has said that focused progress on the electrification of mobility is a logical next step for Indonesia’s energy transition. Following in the footsteps of countries such as China, Vietnam, Thailand and India, Indonesia is recommended to push greater EV adoption, especially in the two-wheeler segment.

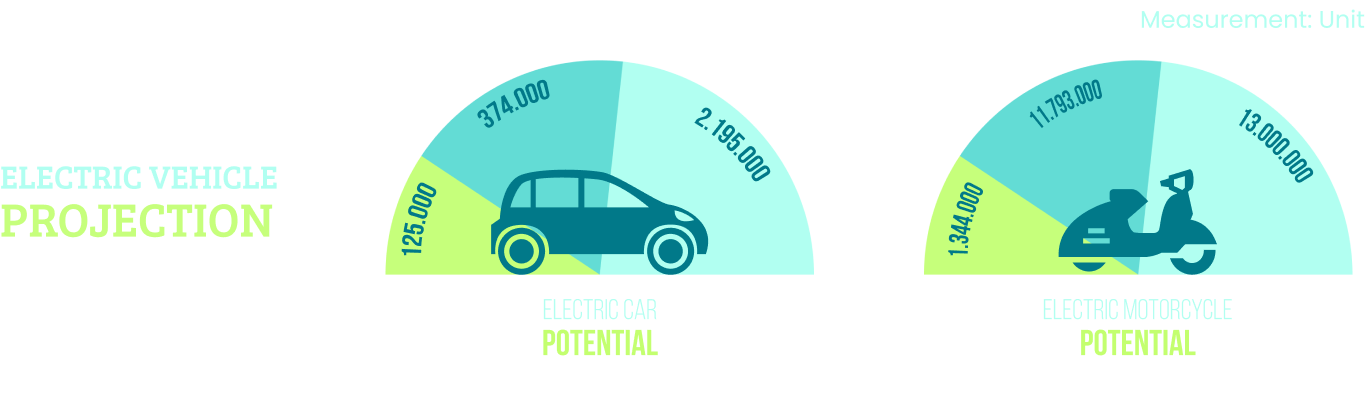

As one of the world’s largest motorcycle markets, the country had around 125.3 million two-wheelers compared with 17.2 million four-wheelers as of December 2022, Statistics Indonesia (BPS) data show. The significant rise of use of EVs is expected to come from motorcycles as people make new purchases or convert their old vehicles.

However, it is predicted that only a fraction of Indonesia’s conventional (internal combustion engine) motorcycles could be replaced by electric ones over the coming years, according to a report by global management consulting firm McKinsey & Company. The high upfront costs and limited driving range of electric motorbikes, among other things, remain barriers to realizing this potential.

Putra Adhiguna, an energy analyst at the Institute of Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), said electric motorcycle sales had risen 191 percent from around 12,000 units in 2021 to 35,000 last year.

Yet, Indonesia would need a continuous annual growth rate of 60 to 70 percent each year until 2030 to get to 1.9 million electric motorcycle sales, he explained.

Indonesia is committed to producing 13 million electric motorbikes and 2.2 million electric cars by 2030.

For users, it is not any easier. Using EVs means more preparation and calculations before every journey.

“If we’re driving on a toll road and use the sport mode to speed up, for example, it will use up more energy,” Arwani said, adding that the brand-holder sole distributor (ATPM) would provide charging assistance if his car runs out of power mid-trip.

Currently, EV users can use mobile applications such as PLN’s Charge.IN or privately owned EVCuzz to accurately locate charging stations.

“Range anxiety was a real issue for me, but as I’ve driven using my electric car for a couple of years, I realized I can overcome the seemingly difficult trips,” he said, nodding to the ostensibly limited number of charging stations currently available outside the Greater Jakarta area.

Meanwhile, Arwani’s electricity bill has not gone up too much since he began using the EV, as the vehicle only accounts for about a fifth of his household’s monthly average electricity usage of 850 to 1,000 kWh.

“In my experience, with a combustion engine car using RON-92 Pertamax fuel, I can spend around Rp 2 million [US$135] to Rp 2.4 million monthly. The electric car I’m currently using, on the other hand, costs me about Rp 250,000 to Rp 300,000 to charge,” Arwani said.

The calculation was made roughly by multiplying the 160 kWh required monthly by the Rp 1,600 per kWh price.

“I’m saving significant money on maintenance and energy compared with when I was still using an internal combustion engine car.”

*Note: Break-even point is the distance that an EV needs to be driven before it does less harm to the environment than a gasoline car.

Source: Reuters

*Note: Break-even point is the distance that an EV needs to be driven before it does less harm to the environment than a gasoline car.

Source: Reuters

The average selling price of EVs is still higher than internal combustion engine vehicles, according to an analysis by Kompas daily, which examined 15 types of electric motorbikes and 69 types of electric cars below Rp 1 billion.

The price of an electric motorbike is approximately Rp 2.9 million more expensive, or 11 percent higher, than an internal combustion engine motorbike.

Meanwhile, electric cars have an average price of Rp 617.5 million. This is Rp 198 million, or 47 percent, more expensive than the price of an internal combustion engine car, which averages Rp 419.9 million.

To resolve the high-cost issue, the government is set to offer financial incentives worth Rp 7 trillion to buyers for the purchase of 800,000 new electric motorcycles and the conversion of 200,000 conventional two-wheelers to electric ones for the 2023-2024 period.

The incentive is expected to push around 1 percent of the motorcycle user population to using EVs by next year.

As for this year, Rp 1.75 trillion of the budget will be rolled out to buyers for the purchase of 200,000 new electric motorcycles and the conversion of 50,000 conventional two-wheelers to electric ones between March 20 and Dec. 31.

Each new electric motorcycle will get Rp 7 million in subsidies, on top of some existing tax breaks.

Meanwhile, incentives for EVs will be given for around 35,800 electric cars and 138 electric buses.

According to Finance Minister Regulation (PMK) No. 38/2023 on the value-added tax (PPN) on electric four-wheelers and electric buses, the incentive will be given in the form of PPN deductions starting April 1, among others. There are yet to be further details on the exact amount of incentives that will be given for each EV purchase as of the time of publication of this article.

Ride-hailing companies like Grab are providing an option for its driver partners to rent their electric motorcycles.

Syahrul, who works as a driver partner for Grab, has been using a electric motorbike since last September, which he rents from the ride-hailing company.

“I only need to pay a daily rental fee of Rp 50,000 and the rest, including maintenance and insurance, is covered by Grab,” he said.

On average, he travels some 1,000 km per week. He uses two replaceable batteries that take four to five hours and around 2.5 kWh of electricity each to fully charge. Together, they give him a range of approximately 120 km.

“I always charge my electric motorbike at home,” Syahrul said. “I enjoy using it, because it’s fuel-efficient and doesn’t produce air or noise pollution.”

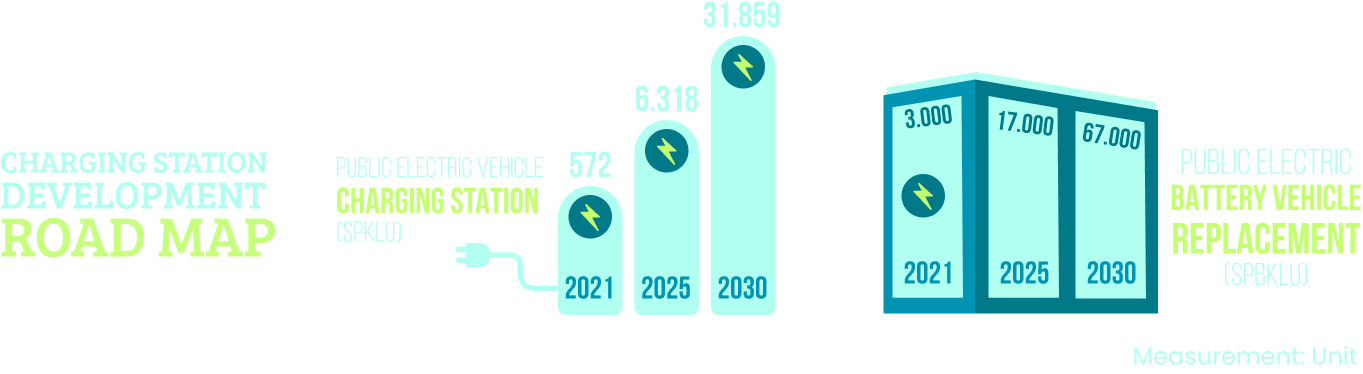

As of Nov. 17, 2022, Indonesia had 439 charging stations in 328 locations and 961 battery swap stations in 961 locations spread across the country, Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry data show. Most of them are located in Java.

This is only a fraction of the 31,000 new charging stations the state-owned electricity giant PLN estimates Indonesia will need to accommodate over 326,000 EVs on the road by 2030.

Meanwhile, the number of battery-swapping stations in Indonesia is expected to reach 52,125 by 2030 to accommodate electric motors, according to the energy ministry and the Agency for the Assessment and Application of Technology (BPPT).

The large disparity of charging stations’ availability means driving EV is only convenient in Java.

Arwani said he drove his car about 350 km on average per week and claimed the battery was “still in pristine condition” after two years.

The car’s 40 kWh battery gives him a week of use when fully charged. The average EV battery capacity is more than 60 kWh, and some EVs on the market offer more than 100 kWh.

Source: Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry

“I found no problem driving 320 km from Wonosobo [in Central Java] to Cirebon [in West Java]. As it turns out, a fully charged battery is enough for the trip. Even if it wasn’t, we could still find charging stations along the way.”

Private and public players need to invest Rp 54.6 trillion to install 31,000 commercial charging stations over the course of 10 years, according to PLN's station development road map.

Over a third of the stations will be in Jakarta, with the rest in cities as far east as Makassar, South Sulawesi. Apart from being located at gas stations, such charging stations will be built at shopping malls, markets and apartment complexes, among other sites with sizable parking lots.

Putra said over its lifetime, an electric vehicle (EV) will have significantly less impact on the environment than its internal combustion engine equivalents.

“As several studies have suggested, EVs aren’t exactly green from the get-go. We need to consider the carbon footprint at the moment they roll off the production line, for instance,” he said.

EV batteries, for example, are built from critical minerals such as manganese, cobalt and nickel, which extractions have caused environmental and labor hazards in Indonesia.

In January, police reported that an Indonesian and a Chinese worker died after a clash broke out following a protest staged by a labor group at PT Gunbuster Nickel Industry (GNI) smelter in North Morowali, Central Sulawesi.

There are also reports from environmental groups about pollution coming from nickel production sites in Sulawesi and the Maluku islands.

The EV batteries disposal once they degrade and become unusable is another issue. These batteries contain hazardous chemicals such as sulfuric acid, as well as heavy metals such as lead and cadmium. Therefore, they can pollute the soil and water if disposed of improperly.

Arwani, who is also the chairman of the Indonesia Electric Car Community (Koleksi), says the Indonesian government has a plan to build factories that will recycle EV batteries.

“Unless the grid that powers EVs adopts cleaner energy sources, the impact of moving from fossil fuel to electric transportation will be negligible,” said Putra.

To make electric cars more sustainable and realize their full environmental and health benefits, stakeholders need to make sure that the electricity supply used for making and running electric cars comes from renewable sources, according to a 2018 European Environment Agency (EEA) report.

“We also have to make sure these cars last. Squeezing the mileage out of every electric car that is being produced is vital,” the report reads.

“So if it is just driven for 70,000 kilometers and then the user stops using it, the overall environmental performance does not look so good compared with conventional cars because the extra energy used for its production is more than that of a conventional car.”

In countries where electricity generation comes intensively from coal, the benefits of EVs are smaller and they can have similar lifetime emissions to the most efficient conventional vehicles, such as hybrid-electric models, climate scientist Zeke Hausfather said in an article published on the United Kingdom-based news site Carbon Brief.

The state-owned electricity company PLN in its 2021-2030 electricity procurement plan has targeted renewable energy capacity in the national energy mix to reach 52 percent or 20.92 gigawatts (GW), while coal-fired plants are expected to fill-in only 13.81 GW or 34 percent.

However, renewable infrastructure progress in Indonesia is painstakingly slow.

Renewable energy share in Indonesia’s primary energy mix has reached only 14.11 percent in 2022. Coal share, on the other hand, increased to 67.21 percent in the same year, representing the 42.1 GW of installed capacity of coal power plants in the country, the Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry data show.

Meaning, unless a user is lucky enough to get all their electricity from residential solar panels, an electric vehicle in Indonesia is actually powered by coal.

Factors affecting solar panel price include the size of the user's roof. In Indonesia, a larger system will cost more in total, but the unit cost per kilowatt-peak (kWp) will be lower and more cost-effective, according to Singapore-based solar panel installer Solar AI.

The company source estimated a 6 kWp system to cost a user approximately Rp 15 million per kWp, but that installing a larger 20 kWp system would cost around Rp 12 million per kWp.

It will take massive investment. Will consumers pay for this?

“Yes, I’m trying to get the best deal to install rooftop solar panels and I know a lot of people from the electric-car community who are interested in them as well,” Arwani said.

Amid an unprecedented expansion in the renewable energy sector, some businesses and individuals have shifted to solar power systems.

The government expects solar power, one of the world’s fastest growing renewable energy technologies, to lead the way to achieving at least 23 percent renewable energy in the country by 2025 and at least 31 percent by 2050, as dictated by the National General Energy Planning (RUEN) road map.

This story was facilitated by funding from the Thomson Reuters Foundation in line with its commitment to advance media freedom, foster more inclusive economies, and promote human rights through its unique services; news, media development, free legal assistance and convening initiatives. However the content of this story is not associated with the Thomson Reuters Foundation, Thomson Reuters, Reuters or any of its affiliates. The Thomson Reuters Foundation is an independent charity registered in the UK and US and is a separate legal entity from Thomson Reuters and Reuters.