As the third-largest lake in the country, Poso Lake in Central Sulawesi was once a place of quiet beauty. Located in Tentena city, about 260 kilometers, an eight-hour drive from Palu, the provincial capital, it is surrounded by rice fields, plantations and buffalo grazing grounds.

In silence, the lake’s waters had a predictable pattern of rising and falling, which had recurred for generations, forming and sustaining life around it.

When the water rose in the first half of the year it was a bounty for fishermen who would welcome a surge of sidat freshwater eels that migrated from Tomini Gulf to the lake through the Poso River. When the water receded in the rest of the year, farmers started to plant and harvest rice and grazed buffaloes.

The serene life around the lake has been disrupted by the opening of the Poso Hydropower Plant in late 2019. The regulating dam of the power plant has caused the lake water to rise, flooding the rice fields and grazing grounds and disrupting the lake and river ecosystem, which has resulted in biodiversity losses.

The serene life around the lake has been disrupted by the opening of the Poso Hydropower Plant in late 2019. The regulating dam of the power plant has caused the lake water to rise, flooding the rice fields and grazing grounds and disrupting the lake and river ecosystem, which has resulted in biodiversity losses.

The serene life around the lake has been disrupted by the opening of the Poso Hydropower Plant in late 2019. The regulating dam of the power plant has caused the lake water to rise, flooding the rice fields and grazing grounds and disrupting the lake and river ecosystem, which has resulted in biodiversity losses.

Built in the heart of Sulawesi, the 515-megawatt hydropower plant is the largest in eastern Indonesia and the third-largest in the country. State-owned electricity company PT PLN has designed the power plant to meet the island’s electricity demand, which has experienced a steep rise due to nickel-mining activities in the central and southern parts of the island.

The company recorded that industrial electricity consumption in the South, Southeast and West Sulawesi (Sulselrabar) division increased 37 percent to 1.7 terawatt hours in 2021. Last year, the consumption rose 61.7 percent, driving total consumption up to 9.5 TWh.

PLN CEO Darmawan Prasodjo said the flow of the river and the lake as live storage produced a large capacity for electricity generation that is critical for the emerging smelter industry, which is powered by the Sulselrabar division. With the operation of the power plant, he said the island had finally utilized renewable energy, which is required for the export of mining commodities.

“PLN is committed to develop industries, especially those related to downstream mining commodities,” he said, during the plant’s inauguration ceremony last year.

The Poso hydroelectric plant is constructed and operated by PT Poso Energy, a company owned by Makassar-based conglomerate Kalla Group run by the family of Jusuf Kalla, a businessman-cum-politician, and a former vice president of Indonesia. Along with other power plants on the island, it sells all the electricity it produces to PLN.

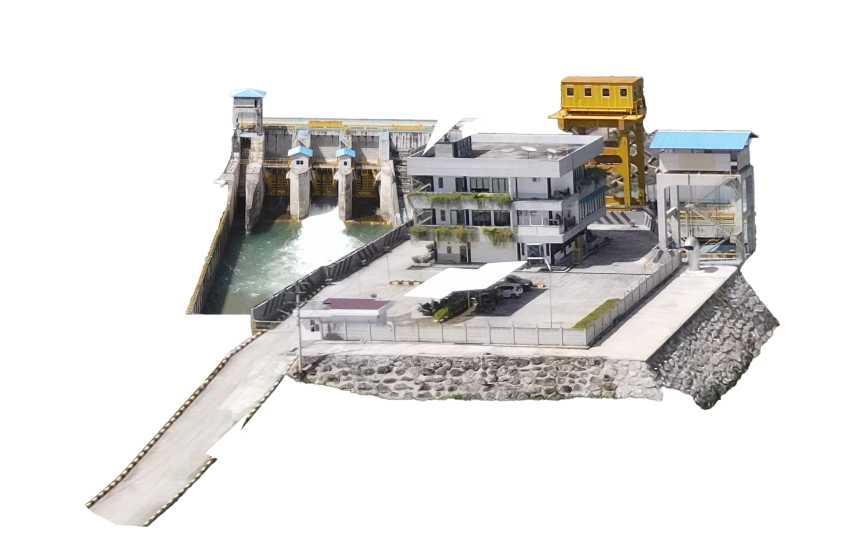

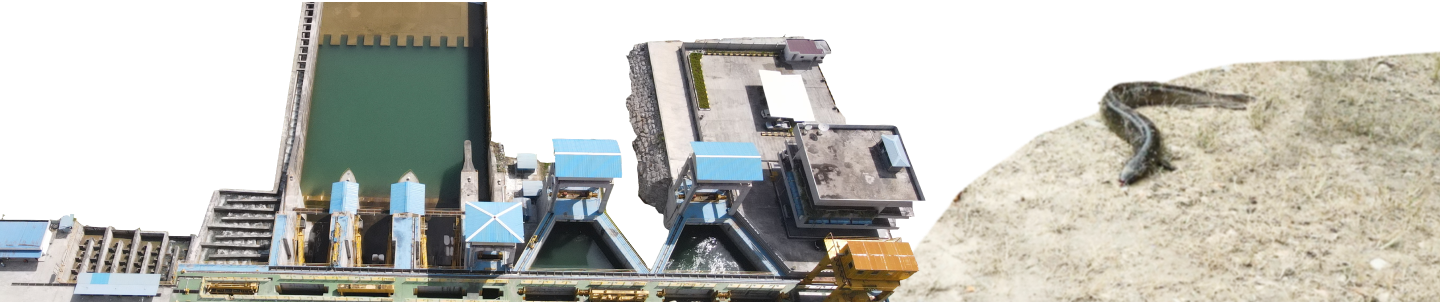

The hydropower plant complex, located on the section of Poso River in Sulewana village, has three powerhouses with generators installed at the site with electricity capacity of 120 MW, 195 MW and 200 MW. The plant is expected to produce up to 1,669 gigawatt hours (GWh) per year to be distributed by PLN to Central Sulawesi, South Sulawesi and Southeast Sulawesi. It is also designed as a peaker plant to meet high demand for electricity during peak hours usually in the late afternoon to evening.

PLN and Poso Energy claim that the plant uses eco-friendly technology. Unlike most hydroelectric plants in the country that use reservoirs, it uses a run-off river system where the river still flows 24 hours. It has built a dam that allocates the water to a turbine and releases the water again to the river. The system is claimed to be greener since it eliminates methane and carbon dioxide emissions caused by the decomposition of organic matter that usually occurs in a reservoir.

But residents around the lake have reported permanent loss of livelihood and biodiversity caused by the hydroelectric dam. Since the operation of the regulating dam, water has risen in Poso Lake, flooding villages in the western and southern parts of the lake.

The Mosintuwu Institute, an environmental research group in Poso, has found that the dam has also blocked the migration of the sidat eels, preventing the fish traveling upstream and causing a decline in the population in the lake. It has also found that dredging in the estuary, aimed to increase water volume to run downstream, has also disrupted the lives of mollusks on the riverbed.

Institute researcher Kurniawan Bandjolu said that every large infrastructure development would always impact the residents surrounding them.

“[Infrastructure] development should be made in accordance with the needs of people [living nearby], not by those outside the vicinity of the hydropower plant. [They] enjoy the electricity while sacrificing local biodiversity and environment,” Kurniawan said.

He hoped that the government would impose more stringent environmental standards to make sure companies are held accountable if their actions damage the environment.

Poso Energy says that the hydropower plant complex included a regulating dam to ensure the water flow needed to generate electricity as well as mitigating the impact of flooding on the upstream and downstream of Poso River.

The company’s environmental manager, Irma Suriani, said that when the company held the trial run of the dam, it coincided with heavy precipitation and a process of improving the capacity of the Poso River.

“Poso Energy has paid compensation to villagers based on harvest losses and claims of livestock deaths during the periods of the trials,” Irma told The Jakarta Post in an email in April.

As of April, the river had undergone 85 percent of the improvement process, which includes dredging to increase the water volume delivered downstream to the dam and prevent flooding.

She also argued that as a source of renewable energy, the hydropower plant produces fewer carbon emissions than a fossil-fuel powered plant with the same capacity. The hydroelectricity, she said, will also help the government to achieve its net-zero carbon emission goals.

Indonesia is aiming to reduce its emissions by 31.9 percent independently, or 43.2 percent with international assistance, by 2030.

The forest and land use sector is expected to be the largest contributor to emissions reduction, accounting for a 25.4 percent reduction in overall emissions from the baseline figure, or 729 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent.

The second-largest is set to be the energy sector, accounting for a 15.5 percent reduction, or 446 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, followed by waste at 1.5 percent, agriculture at 0.4 percent and industries at 0.3 percent.

Freddy Kalengke still vividly remembers the time when he could return to his home with a boatload of sidat, a type of migratory freshwater eel living in and around Poso Lake and the Poso River in Central Sulawesi.

“We caught a lot of sugiri [the local word for the eels] with fish traps. We used to catch 20, 30 even 40 kilograms each night,” Freddy told The Jakarta Post while working on his trap on the Poso River in April.

Freddy’s fish trap was the last one standing in the river mouth, located in Pamona Puselemba district in the northeastern part of the lake and about 18 kilometers, or a half an hour’s drive, from the Poso Hydropower Plant.

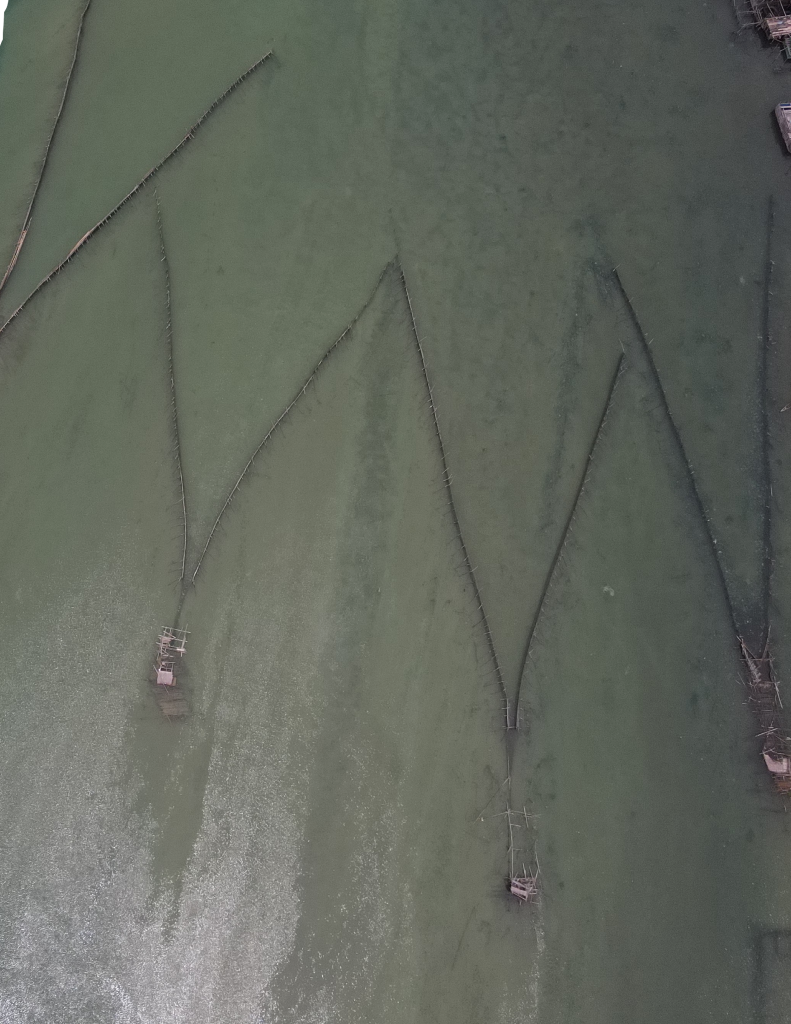

Before the construction of the dam for the plant, there used to be nine fishermen in the area who operated the traditional fish traps, which take the shape of lines of bamboo poles that form a triangle in the river. There used to be hundreds of fishermen using such traps along the river, which stretches 100 km from the lake to Tomini Gulf.

The trap, also known as a “fence” by the fishermen, catches the eels that live in the lake until adulthood before heading to the gulf to spawn. The fishermen remain on guard and even sleep at their fences every night from January to August to harvest the fish.

The fishermen later sell their catch in Tentena district, Poso regency. A kilo of eels sells for around Rp 100,000 (US$6.80). Freddy said he would count himself lucky these days if he could catch 5 kg of eels in one night, a rare event now.

The 55-year-old recalled that the declining eel catch began in 2019 when PT Poso Energy, the operator of the hydropower plant, built the dam on the river, blocking the migratory journey and life cycle of the eels. It also dredged the bottom of the lake and the river to increase the water flow into the hydropower plant dam.

The steep decline in catches has forced the fishermen to look for other sources of income. The other eight fishermen in Pamona Puselemba were willing to dismantle their traps and later received compensation from the company, leaving Freddy as the only one who still operates a trap in the area.

Freddy said the trap was first built by his ancestors in 1826, long before the country’s independence, and was passed from his mother to him.

He said he declined the company’s offer because it was not even close to the value of the fish trap, which he treasures as a legacy from his ancestors. He said the company must pay at least Rp 3 billion for him to dismantle the fence.

“We have our own calculations […] It’s equal to the value of 5kg of catch every night for 60 years,” he said.

Freddy’s wife, Sritati Rakota, 47, said the fish trap helped the family to put two of their three sons through Tadulako University in Palu, the provincial capital of Central Sulawesi. Both major in electric engineering and will graduate soon.

“We won’t change our mind. We will defend our fish trap […] We don’t steal. We’re not robbers. This is our legacy from our ancestors. That’s what makes us strong,” she said.

Kurniawan Bandjolu, a biology researcher and activist for Poso-based environmental group the Mosintuwu Institute, pointed out that the construction of the hydropower plant likely contributed to the declining population of the eels, as the plant construction blocked the fishes’ migratory pattern.

“Traveling upriver is no longer easy for them because of blockage of the [hydropower plant] dam,” Kurniawan said.

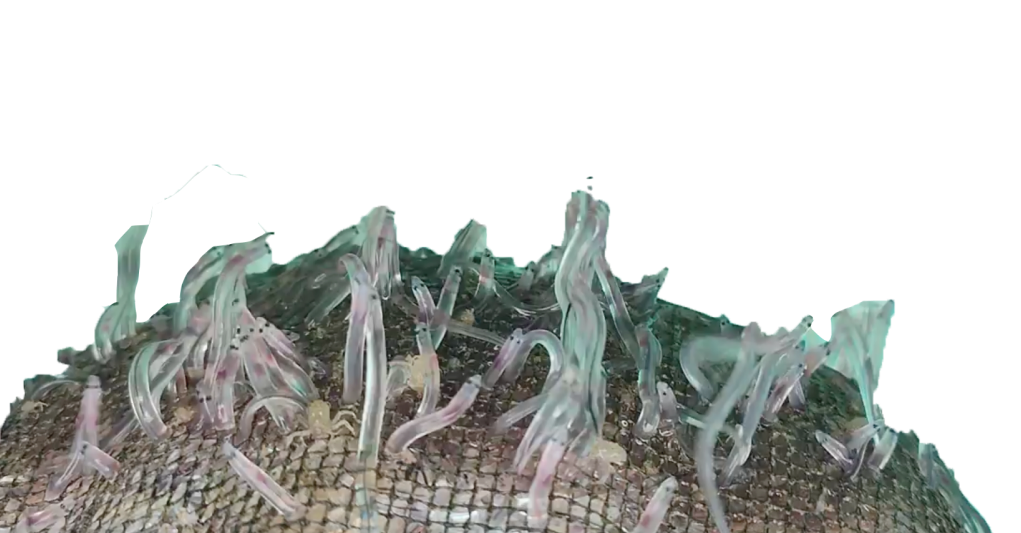

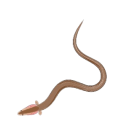

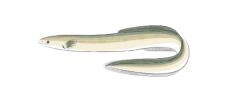

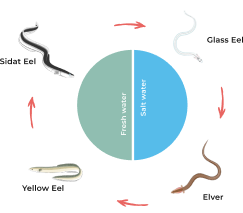

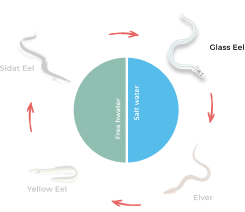

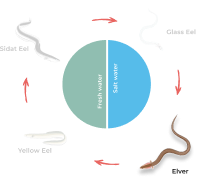

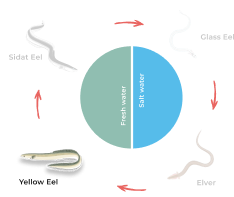

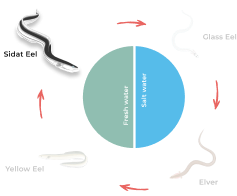

In the Tomini Gulf, the mature sidat will mate and lay eggs. These eggs will hatch into larval eels, which have a leaf-like shape with sizes ranging from 5 to 20 mm. Then they will grow into baby eels, also called glass eels due to their transparent bodies. Their sizes range from 5 to 7 cm.

The glass eels will grow into their juvenile stage, known as elver. Unlike the transparent bodies of glass eels, elver have dark-brown colour with sizes ranging from 9 to 15 cm. Their diet consists of plankton, insects and shrimps.

The eels could spend between five and 25 years at this stage, before migrating upriver back into the Poso Lake through the Poso River.

In Poso Lake, these juvenile eels will grow into their mature stage, also known as yellow eels due to their yellowish colour. Their body size ranges from 40 to 80 cm.

Sexually mature sidat eels live in Poso Lake in Poso, Central Sulawesi. These eels are a dark, silverfish color and range from 80 to 110 centimeters in length. A big sidat eel could reach 1 kilogram in weight. They usually eat shrimps, crabs and clams.

After reaching maturity, these eels will travel from the lake through the Poso River to the Tomini Gulf off the coast of Poso City.

In 2019, the Poso Hydropower Plant began the trial run of its regulating dam. The dam alters the stream of the river, making it difficult for the eels to travel upstream to the lake.

Poso Energy said it built fishways to allow migratory creatures in Poso River like the sidat eels to travel upstream, one of which was shown during a visit by the Post to the hydropower plant.

However, Kurniawan pointed out that there had been no proof or evaluation of how effective the fishways at the hydropower plant’s dam are for the eel population. The Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Ministry and the National Research and Innovation Agency with the help of the institute are still conducting research in which they restock 100,000 eels at the elver stage of development into Poso Lake each year.

“This shows that the fishways’ effectiveness is still up in the air as we still need to manually restock the eels,” Kurniawan said.

He also said that sidat eels were not the only local wildlife species affected by the hydropower plant and dredging of Poso Lake and Poso riverbed.

Native mollusks living in Poso River live in a less-than-ideal habitat as the river is now 10 meters deep due to dredging, reducing the amount of sunlight that the mollusks need to thrive.

“This receives less attention from the people as they [the mollusks] are deemed unimportant. However, they still have a role in balancing the ecosystem such as by being decomposers for dead animals and leaves,” Kurniawan said.

Poso Energy’s environmental manager Irma Suriani said that the regulating dam as well as the regulating weir of the hydropower plant had been equipped with a fishway to help the conservation of fish, including the eels. She also rejected claims that the fish population was endangered by the plant’s operation.

“The sidat is not an endemic species in Poso and exists in other areas including Java Island. The high economic value of the fish has contributed to its declining population,” she told the Post in an emailed reply.

Various studies on the eels have found that out of the 18 species and subspecies in the world, seven are found in Indonesian waters. They are especially found in areas facing deep sea waters like the western coast of Sumatra, the southern coast of Java and the coast of Sulawesi, Maluku and Papua.

By the southeastern shore of Poso Lake, dozens of water buffaloes amble around a grazing ground in Tokilo village. The vast spread of land, which used to be lush greenery, is now mostly submerged under water.

The buffaloes, on the lookout for food, gather on the higher ground, where there is still grass to ruminate on. The rest gambol around or bathe in mud pools or the flooded ground, which now looks like a permanent extension of the lake.

Tokilo is a village of water buffalo breeders with 70 percent of the families owning a herd. Before the lake flooded the area, the 200-hectare grazing ground used to be home to 700 head of buffalo. And the animal means everything for the villagers.

Benhur Bondoke, 52, a buffalo breeder, said the villagers were very dependent on the buffaloes to pay for their children’s education and to put a roof over their heads. The animals are also their health insurance, paying their bills during illness.

“In Tokilo village, now we rarely see houses with rumbia [sago palm tree] leaves. All because of breeding buffaloes,” he told The Jakarta Post while showing the grazing ground.

Benhur said the trial run of the regulating dam of the Poso Hydropower Plant in 2019 and 2020 had caused the flooding and devastated the village. The floodwaters reduced the dry land that supplied the feedstock for the buffaloes.

During the trial run around 90 buffaloes died from starvation, while many others also ran amok during the flooding, invading villagers’ farmlands and even into neighboring villages.

The buffalo herd is now only 400 head.

Benhur said the rise and fall of the lake used to follow certain patterns. From February to June, the water level at the lake was high but low during the drier months of August to February, ensuring that the buffaloes always had abundant grazing land and predictable water levels. Now that cycle is broken.

He said that even if the buffalo herd returned to its previous size, the grazing ground would not be sufficient to feed them since there is now less dry land to allow the animals to feed and rest. The water almost reaches a nearby forest.

“Many farmers have sold their buffaloes rather than keeping them, fearing that the flooding will get worse and leave nothing for the animals,” Benhur said.

Villagers have made contact with PT Poso Energy, the operator of the dam. Stock breeders whose buffaloes died in the floods have already received compensation, although less than demanded from the company. Each breeder only received half the market price of the buffaloes.

For the long term, the company is building a 6-kilometer fence around the grazing lands to prevent the buffaloes from straying into villages and plantations.

Benhur said the villagers were ready to face their uncertain future, whether they like it or not. This includes losing the security of their children’s education and savings to pay for their medical bills.

They are also ready for the fight against the company.

“We will keep pushing them. Poso Energy must take full responsibility for what has happened to our buffaloes,” he said.

There was no wind or rain when the water started to inundate rice fields in Meko, a village on the western shore of Poso Lake. It was harvest time at the beginning of 2020.

The flood, which was caused by the trial run of Poso Hydropower Plant’s regulating dam, wiped out the crops that the farmers had been waiting to harvest.

When the waters receded, Dewa Nyoman Lokawirawan, 42, was so hopeful that he immediately started to plant again.

For generations, farmers in the village followed local weather patterns that affected the rise and fall of the lake. They planted during the dry season from August to February when the water was low and took a break during the rainy season when the levels were high, usually between March and June.

It was this pattern that Dewa and other farmers thought would recur. But the water crept up again, breaking the pattern. When the water rose for the third time and flooded his crop, he finally figured that it was time to abandon the land.

“I thought it was because of nature that that the water failed to recede. But I was wrong. It wasn’t nature. It was because of the corporation,” he said.

And the water has never receded since.

“The most heart-broken were the women in the village. They were distraught about the future of the children. When the rice fields turned yellow and we couldn’t harvest, many started to cry as they saw their hopes drowned by the water,” said Dewa.

Village head I Gede Sukaartana said that since PT Poso Energy began the dam operation, the lake never receded anymore. He said that as many as 114 farmers cultivating 96 hectares of rice fields were affected by the flooding.

After receiving complaints from farmers, Gede tried to bring the matter to the Poso regency administration, regional council (DPRD) and even to the Central Sulawesi governor’s office, but to no avail.

“The farmers took to the streets and directly protested, demanding the company take responsibility,” he said.

Following the protests, Poso Energy finally agreed to compensate the farmers in the form of rice once and cash three times, delivered separately over the past two years. The calculation of compensation was based on the size of each farmer’s rice fields that were flooded, with the latest compensation being disbursed to the farmers’ bank accounts in late 2022.

Dewa and other farmers who lost their rice fields are now forced to look for alternative income.

As his 0.8-ha rice field now lies idle, he has been counting on his durian farm, which is only around 0.25 ha. He said many of his friends have taken any jobs they can get in the village like sapping pine or sugar palm. But the income from this work is not close to what they could earn from their rice farms.

Dewa said the farmers proposed that the company paid rent for their inundated lands as long-term compensation.

Dewa and other farmers who lost their rice fields are now forced to look for alternative income.

As his 0.8-ha rice field now lies idle, he has been counting on his durian farm, which is only around 0.25 ha. He said many of his friends have taken any jobs they can get in the village like sapping pine or sugar palm. But the income from this work is not close to what they could earn from their rice farms.

Dewa said the farmers proposed that the company paid rent for their inundated lands as long-term compensation.

Dewa said the compensation that they received in the past was only enough for daily living, while they were still worried about the future of their children.

Berlin Modjanggo, 63, another farmer, said he and other villagers understood that the electricity that the company generated was important for development and benefited a lot of people throughout Sulawesi.

As one of the world’s major polluters and one of Asia’s thriving economies, Indonesia faces a daunting task, growing its economy fast enough to sustain its population of 270 million while doing so in a sustainable way.

A major obstacle for the country is its reliance on coal, which accounted for 67.2 percent of the country’s energy mix last year. Renewable energy stood far below at 14.1 percent.

The government plans to phase out coal by 2056 and achieve net-zero emissions by 2060. State-owned company PT PLN, which holds a monopoly on the country’s electricity sector, said it will expand its power capacity with clean technologies, increasing the share of renewable energy to 32 percent in 2030 and 69 percent by 2060.

Hydroelectricity is central to the government’s plan to transition to renewable energy. Hydropower is the country’s largest source of renewable energy, contributing around 53 percent of the total renewable energy capacity of 12.5 gigawatts (GW) last year.

The Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry estimates that there is the potential of up to 94 GW of hydropower in the country.

The Poso hydropower plant in Central Sulawesi is among the recent major additions to the country’s power grid. Operating at a capacity of 515 megawatts (MW), the International Hydropower Association (IHA) reported last year that the plant was the most significant addition to the country’s hydroelectricity when it was completed in December 2021.

The report ranked Indonesia sixth among countries with the largest total hydropower capacity at 6,602 MW, surpassing South Korea and New Zealand. In Southeast Asia, it comes third after Vietnam and Laos, which produce 17,333 MW and 8,108 MW, respectively.

Hydroelectricity is central to the government’s plan to transition to renewable energy. Hydropower is the country’s largest source of renewable energy, contributing around 53 percent of the total renewable energy capacity of 12.5 gigawatts (GW) last year.

The Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry estimates that there is the potential of up to 94 GW of hydropower in the country.

The Poso hydropower plant in Central Sulawesi is among the recent major additions to the country’s power grid. Operating at a capacity of 515 megawatts (MW), the International Hydropower Association (IHA) reported last year that the plant was the most significant addition to the country’s hydroelectricity when it was completed in December 2021.

The report ranked Indonesia sixth among countries with the largest total hydropower capacity at 6,602 MW, surpassing South Korea and New Zealand. In Southeast Asia, it comes third after Vietnam and Laos, which produce 17,333 MW and 8,108 MW, respectively.

Hydroelectricity is central to the government’s plan to transition to renewable energy. Hydropower is the country’s largest source of renewable energy, contributing around 53 percent of the total renewable energy capacity of 12.5 gigawatts (GW) last year.

The Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry estimates that there is the potential of up to 94 GW of hydropower in the country.

The Poso hydropower plant in Central Sulawesi is among the recent major additions to the country’s power grid. Operating at a capacity of 515 megawatts (MW), the International Hydropower Association (IHA) reported last year that the plant was the most significant addition to the country’s hydroelectricity when it was completed in December 2021.

The report ranked Indonesia sixth among countries with the largest total hydropower capacity at 6,602 MW, surpassing South Korea and New Zealand. In Southeast Asia, it comes third after Vietnam and Laos, which produce 17,333 MW and 8,108 MW, respectively.

Hydroelectricity is central to the government’s plan to transition to renewable energy. Hydropower is the country’s largest source of renewable energy, contributing around 53 percent of the total renewable energy capacity of 12.5 gigawatts (GW) last year.

The Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry estimates that there is the potential of up to 94 GW of hydropower in the country.

The Poso hydropower plant in Central Sulawesi is among the recent major additions to the country’s power grid. Operating at a capacity of 515 megawatts (MW), the International Hydropower Association (IHA) reported last year that the plant was the most significant addition to the country’s hydroelectricity when it was completed in December 2021.

The report ranked Indonesia sixth among countries with the largest total hydropower capacity at 6,602 MW, surpassing South Korea and New Zealand. In Southeast Asia, it comes third after Vietnam and Laos, which produce 17,333 MW and 8,108 MW, respectively.

But the country’s progress in developing its hydroelectricity has not come without consequences.

Residents around Poso Lake have suffered due to floods and restricted water access caused by the operation of the hydropower plant. Failed harvests along with declining populations of fish and cattle have negatively affected the livelihood of the locals.

Environmental damage has also been reported in Batang Toru, North Sumatra, where another hydroelectric plant is being built. Located within the habitat of the endangered Tapanuli orangutan, the construction of the dam has disrupted the local ecosystem, causing the orangutans to enter nearby villages and farms, even though the plant is not yet operational.

In Purworejo, Central Java, residents have protested the construction of the Bener dam, which they fear will block their access to water resources. Residents of Wadas village, which is located near the dam project, have filed a civil lawsuit against the energy ministry, accusing it of illegal mining of andesite in the village.

Because of these controversies, environmentalists have begun to question the sustainability of hydropower despite its large potential.

Indonesian Forum for the Environment’s (Walhi) campaign manager on spatial planning and infrastructure, Dwi Sawung, said the environmental impact of large scale hydropower outweighed the benefits.

He pointed out that large scale hydropower plants often required a considerable amount of land, which was sometimes acquired by cutting down forests or displacing settlements.

Because of these controversies, environmentalists have begun to question the sustainability of hydropower despite its large potential.

Indonesian Forum for the Environment’s (Walhi) campaign manager on spatial planning and infrastructure, Dwi Sawung, said the environmental impact of large scale hydropower outweighed the benefits.

He pointed out that large scale hydropower plants often required a considerable amount of land, which was sometimes acquired by cutting down forests or displacing settlements.

A study published in American Institute of Biological Sciences’ BioScience journal shows that methane is responsible for 80 percent of the emissions from water storage reservoirs used in hydropower plants. The study examined 267 large reservoirs around the world.

Another study published in Public Library of Science’s PLOS One journal found a global average of 173 kilograms of CO2 and 2.95 kg of CH4 emitted per megawatt hour (MWh) of hydroelectricity produced. This resulted in a combined average carbon footprint of 273 kg CO2e/MWh, or about half of the footprint reported for conventional fossil energy sources. The study analyzed data from 1,500 hydropower plants.

Fabby Tumiwa, the executive director of the Institute for Essential Services Reform (IESR), said although there were social and environmental impacts of hydropower plants, sustainable development is still possible by using internationally developed standards, such as the Hydropower Sustainability Standard developed by the IHA. This standard covers up to 12 environmental, social and governance (ESG) topics from biodiversity conservation to indigenous rights.

“Implementing the standard strictly could minimize the social, environmental and governance impacts [of hydropower plants], so the development of hydropower plants can be done sustainably,” Fabby said.

He also pointed out that financial institutions were increasingly employing ESG standards in risk assessments of projects that they wanted to invest in, so anyone looking into developing hydropower plants should also implement sustainability standards if they want to secure funding.

This story was facilitated by funding from the Thomson Reuters Foundation in line with its commitment to advance media freedom, foster more inclusive economies, and promote human rights through its unique services; news, media development, free legal assistance and convening initiatives. However the content of this story is not associated with the Thomson Reuters Foundation, Thomson Reuters, Reuters or any of its affiliates. The Thomson Reuters Foundation is an independent charity registered in the UK and US and is a separate legal entity from Thomson Reuters and Reuters.

As the third-largest lake in the country, Poso Lake in Central Sulawesi was once a place of quiet beauty. Located in Tentena city, about 260 kilometers, an eight-hour drive from Palu, the provincial capital, it is surrounded by rice fields, plantations and buffalo grazing grounds.

In silence, the lake’s waters had a predictable pattern of rising and falling, which had recurred for generations, forming and sustaining life around it.

When the water rose in the first half of the year it was a bounty for fishermen who would welcome a surge of sidat freshwater eels that migrated from Tomini Gulf to the lake through the Poso River. When the water receded in the rest of the year, farmers started to plant and harvest rice and grazed buffaloes.

The serene life around the lake has been disrupted by the opening of the Poso Hydropower Plant in late 2019. The regulating dam of the power plant has caused the lake water to rise, flooding the rice fields and grazing grounds and disrupting the lake and river ecosystem, which has resulted in biodiversity losses.

The serene life around the lake has been disrupted by the opening of the Poso Hydropower Plant in late 2019. The regulating dam of the power plant has caused the lake water to rise, flooding the rice fields and grazing grounds and disrupting the lake and river ecosystem, which has resulted in biodiversity losses.

The serene life around the lake has been disrupted by the opening of the Poso Hydropower Plant in late 2019. The regulating dam of the power plant has caused the lake water to rise, flooding the rice fields and grazing grounds and disrupting the lake and river ecosystem, which has resulted in biodiversity losses.

Built in the heart of Sulawesi, the 515-megawatt hydropower plant is the largest in eastern Indonesia and the third-largest in the country. State-owned electricity company PT PLN has designed the power plant to meet the island’s electricity demand, which has experienced a steep rise due to nickel-mining activities in the central and southern parts of the island.

The company recorded that industrial electricity consumption in the South, Southeast and West Sulawesi (Sulselrabar) division increased 37 percent to 1.7 terawatt hours in 2021. Last year, the consumption rose 61.7 percent, driving total consumption up to 9.5 TWh.

PLN CEO Darmawan Prasodjo said the flow of the river and the lake as live storage produced a large capacity for electricity generation that is critical for the emerging smelter industry, which is powered by the Sulselrabar division. With the operation of the power plant, he said the island had finally utilized renewable energy, which is required for the export of mining commodities.

“PLN is committed to develop industries, especially those related to downstream mining commodities,” he said, during the plant’s inauguration ceremony last year.

The Poso hydroelectric plant is constructed and operated by PT Poso Energy, a company owned by Makassar-based conglomerate Kalla Group run by the family of Jusuf Kalla, a businessman-cum-politician, and a former vice president of Indonesia. Along with other power plants on the island, it sells all the electricity it produces to PLN.

The hydropower plant complex, located on the section of Poso River in Sulewana village, has three powerhouses with generators installed at the site with electricity capacity of 120 MW, 195 MW and 200 MW. The plant is expected to produce up to 1,669 gigawatt hours (GWh) per year to be distributed by PLN to Central Sulawesi, South Sulawesi and Southeast Sulawesi. It is also designed as a peaker plant to meet high demand for electricity during peak hours usually in the late afternoon to evening.

PLN and Poso Energy claim that the plant uses eco-friendly technology. Unlike most hydroelectric plants in the country that use reservoirs, it uses a run-off river system where the river still flows 24 hours. It has built a dam that allocates the water to a turbine and releases the water again to the river. The system is claimed to be greener since it eliminates methane and carbon dioxide emissions caused by the decomposition of organic matter that usually occurs in a reservoir.

But residents around the lake have reported permanent loss of livelihood and biodiversity caused by the hydroelectric dam. Since the operation of the regulating dam, water has risen in Poso Lake, flooding villages in the western and southern parts of the lake.

The Mosintuwu Institute, an environmental research group in Poso, has found that the dam has also blocked the migration of the sidat eels, preventing the fish traveling upstream and causing a decline in the population in the lake. It has also found that dredging in the estuary, aimed to increase water volume to run downstream, has also disrupted the lives of mollusks on the riverbed.

Institute researcher Kurniawan Bandjolu said that every large infrastructure development would always impact the residents surrounding them.

“[Infrastructure] development should be made in accordance with the needs of people [living nearby], not by those outside the vicinity of the hydropower plant. [They] enjoy the electricity while sacrificing local biodiversity and environment,” Kurniawan said.

He hoped that the government would impose more stringent environmental standards to make sure companies are held accountable if their actions damage the environment.

Poso Energy says that the hydropower plant complex included a regulating dam to ensure the water flow needed to generate electricity as well as mitigating the impact of flooding on the upstream and downstream of Poso River.

The company’s environmental manager, Irma Suriani, said that when the company held the trial run of the dam, it coincided with heavy precipitation and a process of improving the capacity of the Poso River.

“Poso Energy has paid compensation to villagers based on harvest losses and claims of livestock deaths during the periods of the trials,” Irma told The Jakarta Post in an email in April.

As of April, the river had undergone 85 percent of the improvement process, which includes dredging to increase the water volume delivered downstream to the dam and prevent flooding.

She also argued that as a source of renewable energy, the hydropower plant produces fewer carbon emissions than a fossil-fuel powered plant with the same capacity. The hydroelectricity, she said, will also help the government to achieve its net-zero carbon emission goals.

Indonesia is aiming to reduce its emissions by 31.9 percent independently, or 43.2 percent with international assistance, by 2030.

The forest and land use sector is expected to be the largest contributor to emissions reduction, accounting for a 25.4 percent reduction in overall emissions from the baseline figure, or 729 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent.

The second-largest is set to be the energy sector, accounting for a 15.5 percent reduction, or 446 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, followed by waste at 1.5 percent, agriculture at 0.4 percent and industries at 0.3 percent.

Freddy Kalengke still vividly remembers the time when he could return to his home with a boatload of sidat, a type of migratory freshwater eel living in and around Poso Lake and the Poso River in Central Sulawesi.

“We caught a lot of sugiri [the local word for the eels] with fish traps. We used to catch 20, 30 even 40 kilograms each night,” Freddy told The Jakarta Post while working on his trap on the Poso River in April.

Freddy’s fish trap was the last one standing in the river mouth, located in Pamona Puselemba district in the northeastern part of the lake and about 18 kilometers, or a half an hour’s drive, from the Poso Hydropower Plant.

Before the construction of the dam for the plant, there used to be nine fishermen in the area who operated the traditional fish traps, which take the shape of lines of bamboo poles that form a triangle in the river. There used to be hundreds of fishermen using such traps along the river, which stretches 100 km from the lake to Tomini Gulf.

The trap, also known as a “fence” by the fishermen, catches the eels that live in the lake until adulthood before heading to the gulf to spawn. The fishermen remain on guard and even sleep at their fences every night from January to August to harvest the fish.

The fishermen later sell their catch in Tentena district, Poso regency. A kilo of eels sells for around Rp 100,000 (US$6.80). Freddy said he would count himself lucky these days if he could catch 5 kg of eels in one night, a rare event now.

The 55-year-old recalled that the declining eel catch began in 2019 when PT Poso Energy, the operator of the hydropower plant, built the dam on the river, blocking the migratory journey and life cycle of the eels. It also dredged the bottom of the lake and the river to increase the water flow into the hydropower plant dam.

The steep decline in catches has forced the fishermen to look for other sources of income. The other eight fishermen in Pamona Puselemba were willing to dismantle their traps and later received compensation from the company, leaving Freddy as the only one who still operates a trap in the area.

Freddy said the trap was first built by his ancestors in 1826, long before the country’s independence, and was passed from his mother to him.

He said he declined the company’s offer because it was not even close to the value of the fish trap, which he treasures as a legacy from his ancestors. He said the company must pay at least Rp 3 billion for him to dismantle the fence.

“We have our own calculations […] It’s equal to the value of 5kg of catch every night for 60 years,” he said.

Freddy’s wife, Sritati Rakota, 47, said the fish trap helped the family to put two of their three sons through Tadulako University in Palu, the provincial capital of Central Sulawesi. Both major in electric engineering and will graduate soon.

“We won’t change our mind. We will defend our fish trap […] We don’t steal. We’re not robbers. This is our legacy from our ancestors. That’s what makes us strong,” she said.

Kurniawan Bandjolu, a biology researcher and activist for Poso-based environmental group the Mosintuwu Institute, pointed out that the construction of the hydropower plant likely contributed to the declining population of the eels, as the plant construction blocked the fishes’ migratory pattern.

“Traveling upriver is no longer easy for them because of blockage of the [hydropower plant] dam,” Kurniawan said.

In the Tomini Gulf, the mature sidat will mate and lay eggs. These eggs will hatch into larval eels, which have a leaf-like shape with sizes ranging from 5 to 20 mm. Then they will grow into baby eels, also called glass eels due to their transparent bodies. Their sizes range from 5 to 7 cm.

The glass eels will grow into their juvenile stage, known as elver. Unlike the transparent bodies of glass eels, elver have dark-brown colour with sizes ranging from 9 to 15 cm. Their diet consists of plankton, insects and shrimps.

The eels could spend between five and 25 years at this stage, before migrating upriver back into the Poso Lake through the Poso River.

In Poso Lake, these juvenile eels will grow into their mature stage, also known as yellow eels due to their yellowish colour. Their body size ranges from 40 to 80 cm.

Sexually mature sidat eels live in Poso Lake in Poso, Central Sulawesi. These eels are a dark, silverfish color and range from 80 to 110 centimeters in length. A big sidat eel could reach 1 kilogram in weight. They usually eat shrimps, crabs and clams.

After reaching maturity, these eels will travel from the lake through the Poso River to the Tomini Gulf off the coast of Poso City.

In 2019, the Poso Hydropower Plant began the trial run of its regulating dam. The dam alters the stream of the river, making it difficult for the eels to travel upstream to the lake.

Poso Energy said it built fishways to allow migratory creatures in Poso River like the sidat eels to travel upstream, one of which was shown during a visit by the Post to the hydropower plant.

However, Kurniawan pointed out that there had been no proof or evaluation of how effective the fishways at the hydropower plant’s dam are for the eel population. The Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Ministry and the National Research and Innovation Agency with the help of the institute are still conducting research in which they restock 100,000 eels at the elver stage of development into Poso Lake each year.

“This shows that the fishways’ effectiveness is still up in the air as we still need to manually restock the eels,” Kurniawan said.

He also said that sidat eels were not the only local wildlife species affected by the hydropower plant and dredging of Poso Lake and Poso riverbed.

Native mollusks living in Poso River live in a less-than-ideal habitat as the river is now 10 meters deep due to dredging, reducing the amount of sunlight that the mollusks need to thrive.

“This receives less attention from the people as they [the mollusks] are deemed unimportant. However, they still have a role in balancing the ecosystem such as by being decomposers for dead animals and leaves,” Kurniawan said.

Poso Energy’s environmental manager Irma Suriani said that the regulating dam as well as the regulating weir of the hydropower plant had been equipped with a fishway to help the conservation of fish, including the eels. She also rejected claims that the fish population was endangered by the plant’s operation.

“The sidat is not an endemic species in Poso and exists in other areas including Java Island. The high economic value of the fish has contributed to its declining population,” she told the Post in an emailed reply.

Various studies on the eels have found that out of the 18 species and subspecies in the world, seven are found in Indonesian waters. They are especially found in areas facing deep sea waters like the western coast of Sumatra, the southern coast of Java and the coast of Sulawesi, Maluku and Papua.

By the southeastern shore of Poso Lake, dozens of water buffaloes amble around a grazing ground in Tokilo village. The vast spread of land, which used to be lush greenery, is now mostly submerged under water.

The buffaloes, on the lookout for food, gather on the higher ground, where there is still grass to ruminate on. The rest gambol around or bathe in mud pools or the flooded ground, which now looks like a permanent extension of the lake.

Tokilo is a village of water buffalo breeders with 70 percent of the families owning a herd. Before the lake flooded the area, the 200-hectare grazing ground used to be home to 700 head of buffalo. And the animal means everything for the villagers.

Benhur Bondoke, 52, a buffalo breeder, said the villagers were very dependent on the buffaloes to pay for their children’s education and to put a roof over their heads. The animals are also their health insurance, paying their bills during illness.

“In Tokilo village, now we rarely see houses with rumbia [sago palm tree] leaves. All because of breeding buffaloes,” he told The Jakarta Post while showing the grazing ground.

Benhur said the trial run of the regulating dam of the Poso Hydropower Plant in 2019 and 2020 had caused the flooding and devastated the village. The floodwaters reduced the dry land that supplied the feedstock for the buffaloes.

During the trial run around 90 buffaloes died from starvation, while many others also ran amok during the flooding, invading villagers’ farmlands and even into neighboring villages.

The buffalo herd is now only 400 head.

Benhur said the rise and fall of the lake used to follow certain patterns. From February to June, the water level at the lake was high but low during the drier months of August to February, ensuring that the buffaloes always had abundant grazing land and predictable water levels. Now that cycle is broken.

He said that even if the buffalo herd returned to its previous size, the grazing ground would not be sufficient to feed them since there is now less dry land to allow the animals to feed and rest. The water almost reaches a nearby forest.

“Many farmers have sold their buffaloes rather than keeping them, fearing that the flooding will get worse and leave nothing for the animals,” Benhur said.

Villagers have made contact with PT Poso Energy, the operator of the dam. Stock breeders whose buffaloes died in the floods have already received compensation, although less than demanded from the company. Each breeder only received half the market price of the buffaloes.

For the long term, the company is building a 6-kilometer fence around the grazing lands to prevent the buffaloes from straying into villages and plantations.

Benhur said the villagers were ready to face their uncertain future, whether they like it or not. This includes losing the security of their children’s education and savings to pay for their medical bills.

They are also ready for the fight against the company.

“We will keep pushing them. Poso Energy must take full responsibility for what has happened to our buffaloes,” he said.

There was no wind or rain when the water started to inundate rice fields in Meko, a village on the western shore of Poso Lake. It was harvest time at the beginning of 2020.

The flood, which was caused by the trial run of Poso Hydropower Plant’s regulating dam, wiped out the crops that the farmers had been waiting to harvest.

When the waters receded, Dewa Nyoman Lokawirawan, 42, was so hopeful that he immediately started to plant again.

For generations, farmers in the village followed local weather patterns that affected the rise and fall of the lake. They planted during the dry season from August to February when the water was low and took a break during the rainy season when the levels were high, usually between March and June.

It was this pattern that Dewa and other farmers thought would recur. But the water crept up again, breaking the pattern. When the water rose for the third time and flooded his crop, he finally figured that it was time to abandon the land.

“I thought it was because of nature that that the water failed to recede. But I was wrong. It wasn’t nature. It was because of the corporation,” he said.

And the water has never receded since.

“The most heart-broken were the women in the village. They were distraught about the future of the children. When the rice fields turned yellow and we couldn’t harvest, many started to cry as they saw their hopes drowned by the water,” said Dewa.

Village head I Gede Sukaartana said that since PT Poso Energy began the dam operation, the lake never receded anymore. He said that as many as 114 farmers cultivating 96 hectares of rice fields were affected by the flooding.

After receiving complaints from farmers, Gede tried to bring the matter to the Poso regency administration, regional council (DPRD) and even to the Central Sulawesi governor’s office, but to no avail.

“The farmers took to the streets and directly protested, demanding the company take responsibility,” he said.

Following the protests, Poso Energy finally agreed to compensate the farmers in the form of rice once and cash three times, delivered separately over the past two years. The calculation of compensation was based on the size of each farmer’s rice fields that were flooded, with the latest compensation being disbursed to the farmers’ bank accounts in late 2022.

Dewa and other farmers who lost their rice fields are now forced to look for alternative income.

As his 0.8-ha rice field now lies idle, he has been counting on his durian farm, which is only around 0.25 ha. He said many of his friends have taken any jobs they can get in the village like sapping pine or sugar palm. But the income from this work is not close to what they could earn from their rice farms.

Dewa said the farmers proposed that the company paid rent for their inundated lands as long-term compensation.

Dewa said the compensation that they received in the past was only enough for daily living, while they were still worried about the future of their children.

Berlin Modjanggo, 63, another farmer, said he and other villagers understood that the electricity that the company generated was important for development and benefited a lot of people throughout Sulawesi.

As one of the world’s major polluters and one of Asia’s thriving economies, Indonesia faces a daunting task, growing its economy fast enough to sustain its population of 270 million while doing so in a sustainable way.

A major obstacle for the country is its reliance on coal, which accounted for 67.2 percent of the country’s energy mix last year. Renewable energy stood far below at 14.1 percent.

The government plans to phase out coal by 2056 and achieve net-zero emissions by 2060. State-owned company PT PLN, which holds a monopoly on the country’s electricity sector, said it will expand its power capacity with clean technologies, increasing the share of renewable energy to 32 percent in 2030 and 69 percent by 2060.

Hydroelectricity is central to the government’s plan to transition to renewable energy. Hydropower is the country’s largest source of renewable energy, contributing around 53 percent of the total renewable energy capacity of 12.5 gigawatts (GW) last year.

The Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry estimates that there is the potential of up to 94 GW of hydropower in the country.

The Poso hydropower plant in Central Sulawesi is among the recent major additions to the country’s power grid. Operating at a capacity of 515 megawatts (MW), the International Hydropower Association (IHA) reported last year that the plant was the most significant addition to the country’s hydroelectricity when it was completed in December 2021.

The report ranked Indonesia sixth among countries with the largest total hydropower capacity at 6,602 MW, surpassing South Korea and New Zealand. In Southeast Asia, it comes third after Vietnam and Laos, which produce 17,333 MW and 8,108 MW, respectively.

The report ranked Indonesia sixth among countries with the largest total hydropower capacity at 6,602 MW, surpassing South Korea and New Zealand. In Southeast Asia, it comes third after Vietnam and Laos, which produce 17,333 MW and 8,108 MW, respectively.

But the country’s progress in developing its hydroelectricity has not come without consequences.

Residents around Poso Lake have suffered due to floods and restricted water access caused by the operation of the hydropower plant. Failed harvests along with declining populations of fish and cattle have negatively affected the livelihood of the locals.

Environmental damage has also been reported in Batang Toru, North Sumatra, where another hydroelectric plant is being built. Located within the habitat of the endangered Tapanuli orangutan, the construction of the dam has disrupted the local ecosystem, causing the orangutans to enter nearby villages and farms, even though the plant is not yet operational.

In Purworejo, Central Java, residents have protested the construction of the Bener dam, which they fear will block their access to water resources. Residents of Wadas village, which is located near the dam project, have filed a civil lawsuit against the energy ministry, accusing it of illegal mining of andesite in the village.

Because of these controversies, environmentalists have begun to question the sustainability of hydropower despite its large potential.

Indonesian Forum for the Environment’s (Walhi) campaign manager on spatial planning and infrastructure, Dwi Sawung, said the environmental impact of large scale hydropower outweighed the benefits.

He pointed out that large scale hydropower plants often required a considerable amount of land, which was sometimes acquired by cutting down forests or displacing settlements.

Indonesian Forum for the Environment’s (Walhi) campaign manager on spatial planning and infrastructure, Dwi Sawung, said the environmental impact of large scale hydropower outweighed the benefits.

He pointed out that large scale hydropower plants often required a considerable amount of land, which was sometimes acquired by cutting down forests or displacing settlements.

A study published in American Institute of Biological Sciences’ BioScience journal shows that methane is responsible for 80 percent of the emissions from water storage reservoirs used in hydropower plants. The study examined 267 large reservoirs around the world.

Another study published in Public Library of Science’s PLOS One journal found a global average of 173 kilograms of CO2 and 2.95 kg of CH4 emitted per megawatt hour (MWh) of hydroelectricity produced. This resulted in a combined average carbon footprint of 273 kg CO2e/MWh, or about half of the footprint reported for conventional fossil energy sources. The study analyzed data from 1,500 hydropower plants.

Fabby Tumiwa, the executive director of the Institute for Essential Services Reform (IESR), said although there were social and environmental impacts of hydropower plants, sustainable development is still possible by using internationally developed standards, such as the Hydropower Sustainability Standard developed by the IHA. This standard covers up to 12 environmental, social and governance (ESG) topics from biodiversity conservation to indigenous rights.

“Implementing the standard strictly could minimize the social, environmental and governance impacts [of hydropower plants], so the development of hydropower plants can be done sustainably,” Fabby said.

He also pointed out that financial institutions were increasingly employing ESG standards in risk assessments of projects that they wanted to invest in, so anyone looking into developing hydropower plants should also implement sustainability standards if they want to secure funding.

This story was facilitated by funding from the Thomson Reuters Foundation in line with its commitment to advance media freedom, foster more inclusive economies, and promote human rights through its unique services; news, media development, free legal assistance and convening initiatives. However the content of this story is not associated with the Thomson Reuters Foundation, Thomson Reuters, Reuters or any of its affiliates. The Thomson Reuters Foundation is an independent charity registered in the UK and US and is a separate legal entity from Thomson Reuters and Reuters.