Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

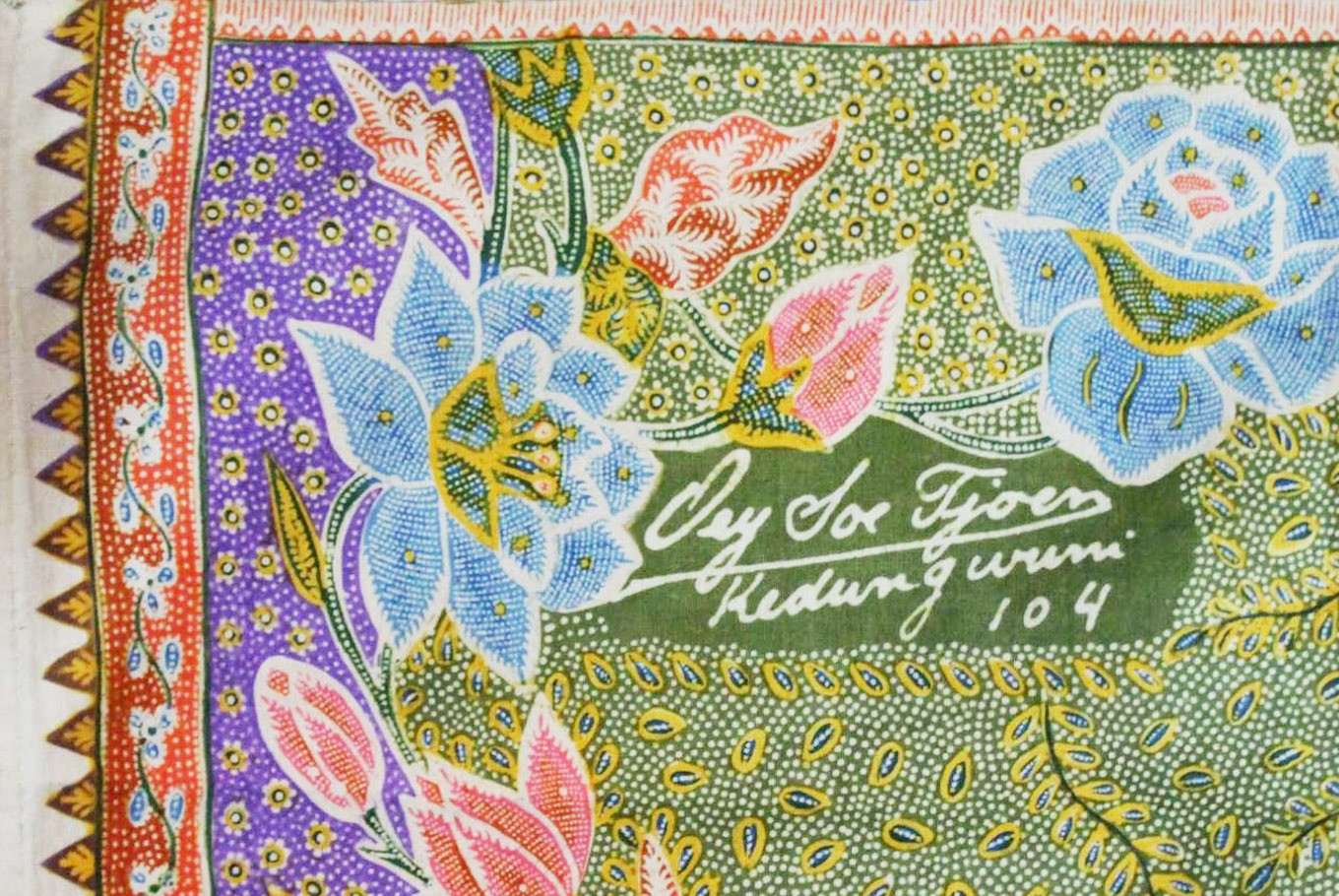

View all search resultsCultural legacy of Oey Soe Tjoen batik

Oey Soe Tjoen's creations are considered a true Indonesian cultural touchstone.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

B

atik is one of Indonesia’s most recognizable cultural trademarks, with designs that weave together meaningful traditional patterns and symbols that convey many expressions and distinctive nuances.

However, not many batik lines capture these expressions and nuances quite like batik master Oey Soe Tjoen, whose creations are considered a true Indonesian cultural touchstone.

Started in 1925 in Pekalongan, one of Central Java’s batik centers, Oey Soe Tjoen, the business named after its founder, was one of the first examples of Indonesian-Chinese made batik. At that time, Oey Soe Tjoen broke away from his family’s printed batik business to start his own hand-drawn batik line.

Now, in its 92nd year of business, Oey’s granddaughter, Widianti Widjaja is at the helm of the family business, as well as taking up the role as designer. She took the reins after her father’s death in 2002. At the time, she was only a few days into college.

Read also: Preserving Go Tik Swan batik legacy

Widianti said she had received countless words of appreciation from batik collectors, some of whom often reminded her to not feel pressured into conforming to specific design aspects and encouraged her to make and sell the kind of batik she wanted to.

“Some collectors have advised me not to take specific orders when making batik, because doing so would [subtly] affect my creativity,” she said during a discussion held as part of an exhibition at Jakarta’s Kunstkring Paleis Gallery in Menteng, Central Jakarta.

Decades of tradition: Widianti Widjaja, Oey’s granddaughter, displays an Oey Soe Tjoen batik piece. (Intisari/File)Around 40 batik pieces were displayed at the “Oey Soe Tjoen Batik Exhibition: A Tribute for Culture” held in partnership with private lender Bank Central Asia (BCA) and Wastra Indonesia, an organization founded with the aim to preserve Indonesian fabrics.

The vintage pieces on display were known for the distinctive ways their floral and animal patterns were designed.

In order to maintain her creativity, Widianti has vowed to keep an open mind when crafting batik designs, crediting her openness, which allows her to explore new ideas beyond the same old batik patterns, as the reason behind the uniqueness of her works.

With the large weight placed on her shoulders by the legacy of the Oey Soe Tjoen dynasty and the demands of the batik industry, Widianti is full of sheer determination, despite her claim that creating batik is always considered “second” to her devotion to her husband and children.

She only draws at night, after her family has settled in, but can spend up to four hours either coming up with new designs or perfecting those in progress. “The devotion I have for batik is strong, but I will always put my family’s needs first over everything else,” she said.

Oey Soe Tjoen batik pieces, with their complex designs and meticulous production methods, are considered very difficult to reproduce and, as such, are deemed to be rare items.

A particular piece usually requires a dozen or so non-full-time workers to complete, and the more complicated the design, the longer it takes to finish. The process is therefore very expensive and time consuming, with it possible for a single piece to take up to a year-and-a-half to complete.

During the company’s golden years in the 1930s, the Oey Soe Tjoen batik line was able to produce 30 pieces of batik per month with a workforce of over 150 people.

As such, any new prints made by Widianti for the Oey line usually fetch prices in the millions of rupiah because of their scarcity and the length of production.

The kind of vintage batik Oey Soe Tjoen produces is made with a more fragile, delicate method than modern batik. The maintenance of its pieces, specifically those that are on display in museums, must adhere to strict climate control measures and meticulous, delicate cleaning because something as small as a spec of dust or improper lighting could basically “tear the batik like a knife.”

Throughout its history, Oey Soe Tjoen batik has been collected, exhibited and sold all around the world, such as in Europe, Japan, Singapore and the United States. The scarcity of its pieces has also bred a black market industry of fakes, with several fake Oey Soe Tjoen prints in circulation.

Widianti claims the deluge of forged prints contributed to diminishing her family’s business back in the 1980s, and remains a threat today.

A collector, who attended the exhibition and had experience being offered fake Oey prints, said the biggest giveaway was usually the price. “There is a saying among collectors. If anyone were to offer you an Oey Soe Tjoen batik for less than Rp 150 million (US$11,278) then it would definitely be a fake,” the collector said.

![Let it out: Japanese rocker Hyde holds a solo concert, billed as the Hyde [Inside] Live 2025 World Tour in Jakarta, on Nov. 1, 2025, at Tennis Indoor Senayan in Central Jakarta.

(Courtesy of Sound Rhythm and Mataloka Live)](https://img.jakpost.net/c/2025/11/05/2025_11_05_168574_1762306300._medium.jpg)