Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsA mountain like no other

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

Ancient myths and texts narrate the importance of Mount Agung and the destruction brought by its past eruptions.

The main road that connects Selat and Sebudi, two villages in the danger zone of Mount Agung, was empty on that cool and cloudy morning. On normal days, it is a busy thoroughfare as hundreds of trucks transport sand and pebbles from massive quarries in Sebudi to cities across Bali.

Those quarries are the “gift” the tallest peak bestows on locals in the aftermath of the 1963 eruption.

Most villagers had evacuated to Sidemen and the quarries were closed down.

“I don’t think it will erupt any time soon,” I Gusti Lanang Rai said as he lit a cigarette.

A tough-looking man, Rai is the village’s security coordinator, who is tasked with operating the eruption warning siren installed in the village. He is also a proud owner of two quarries in Sebudi.

“Our elders say that in 1963, prior to the eruption, torrential rains hit the village for many days, causing a major flood and landslide. Right after that, the mist that covered Mt. Agung changed color from white to black, and only after that, the eruption occurred,” he said.

“We haven’t experienced any flooding yet, so I still feel quite safe.”

That Mother Nature would offer a clear warning sign prior to an eruption is a common narrative shared by villagers who live along the slope of the majestic mountain, and whose elders experienced the 1963 eruption. It sprung from the belief that Mt. Agung is not just a common volcano, but also the throne of its supreme protecting deity.

It is a geographical landmark as well as a supernatural axis mundi.

Experts: Ida I. Dewa Gde Catra (left) and Sugi Lanus expound the narrative on Mt. Agung written in ancient lontar (palm-leaf manuscripts). (JP/Zul Trio Anggono)Sugi Lanus, a lontar (palm leaf) manuscript scholar, and Ida I Dewa Gde Catra, an elderly lontar expert who is revered by experts here and abroad, explained that scores of ancient lontar manuscripts narrate the importance of Mt. Agung to the island’s cosmology and the sacred rites to maintain cosmic balance.

“Usana Bali, Sulayang Gni, Tattwa Batur Kalawasan, Babad Tusan and Babad Pasek are some of the ancient texts that dwell on this subject matter,” Sugi Lanus said.

Mt. Agung occupies a paramount position because the island’s ruling deity is said to be “born” out of its caldera. This origin story involves a violent eruption of the peak.

The deity’s is called Hyang Putrajaya, but the Balinese prefer to address him with his honorific title, Ida Bhatara Lingsir Giri Tohlangkir, the Elder Deity of Mt. Agung. Tohlangkir is Mt. Agung’s name in ancient Balinese lontar manuscripts.

Babad Pasek, a semi-mythological text on the history and genealogy of Pasek Sanak Sapta Rsi, Bali’s largest clan, narrates how the supreme deity Pasupati chopped off a part of Mt. Semeru in Java before flying it to Bali and placing it on the island’s northeast region in order to stabilize the then floating land mass. The event is said to have taken place in Caka year 11 (89 AD).

According to the text, the new peak later erupted, first in 105 AD and later in 109 AD. It is said that after the second eruption, Hyang Putrajaya and his sister Dewi Danu rose from the flaming caldera.

Pasupati later told Hyang Putrajaya to reside in Mt. Agung, Dewi Danu in Lake Batur and her little brother, Hyang Gnijaya, in Mt. Lempuyang. Pasupati tasked them to be the divine rulers of the island, responsible for providing islanders with protection and prosperity.

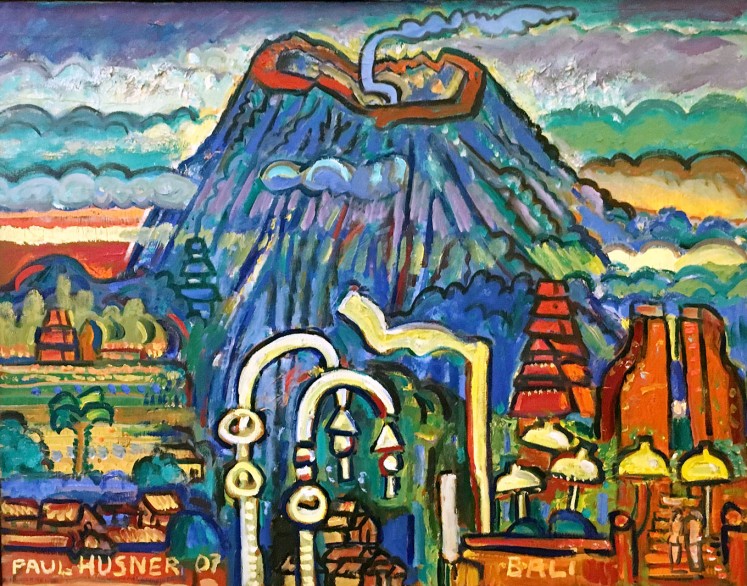

Colorful: View at the Volcano from Sidemen's Red Temples by Swiss-born artist Paul Husner. Mt. Agung is a recurring visual element in his works. (JP/I Wayan Juniarta)Another ancient text, Usana Bali, gives a slightly different account. It tells the story of Pasupati carrying two parts of Mt. Sumeru to Bali; one part became Mt. Agung and the second, Mt. Batur.

“Basically, these three deities are the ‘indigenous’ deities of Bali, because their names are not known in any Indian Hindu texts, and to this day, they hold a very important position in both the spiritual and physical lives of Balinese Hindus,” Sugi Lanus said.

The Besakih temple complex initally a hermitage of sage Kulputih that was expanded in the 13th century into a major temple by revered priest Danghyang Markandeya, is first and foremost a place of worship dedicated to Hyang Putrajaya.

Later on, influential kings of ancient Bali were immortalized in multi-tiered meru shrines in the temple compound and every clan in Bali built minor temples to house their ancestral spirits next to Besakih’s inner sanctum, a development that earned Besakih its status as the island’s Mother Temple.

“From a spiritual point of view, the temple is the island’s largest, and the most important congregation of ancestral spirits and great royals. And all of them gravitate around Mt. Agung, the seat of Hyang Putrajaya,” Sugi Lanus said.

It is in Besakih and Mt. Agung that Balinese Hindus organize their most important rituals: the decennial Panca Bali Krama and the centennial Eka Dasa Rudra. Both are sacrificial rituals aimed at restoring the balance of the universe.

The eruption of Mt. Agung throughout the history of ancient Bali was also recorded in several ancient lontar texts, including Babad Gumi, a chronological compendium of major historical events in Bali.

The texts mentioned that the volcano erupted at least eight times between 11th and 19th century, with the eruption in 1711 portrayed as the most destructive, killing a large number of people in nine villages on its slope.

Interestingly, Mt. Agung’s eruption is also seen by the Balinese as an omen for a much darker event to come.

The late Ida Pedanda Made Sidemen, arguably the most influential kawi-wiku (poet priest) in the history of contemporary Bali, in the colophon of his Puja Panambutan writes: “In 1963, Mt. Agung erupted, spewing lava, volcanic ash and flying boulders […] In 1965, political parties triggered chaos in the country […] On the fourth moon, a comet was seen in the eastern sky, a landslide swept two huge boulders, each the size of a house.”

The priest weaved a connection between the comet and landslide with the volcanic eruption and the 1965 bloodbath, reinforcing the traditional belief that the “wrath” of Nature is an ominous sign for imminent and violent political or social turbulence.

“Hopefully, that will not be the case. But I am certain that an eruption, any eruption, will not diminish the Balinese people’s respect and adoration of Mt. Agung,” Sugi Lanus said.