Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

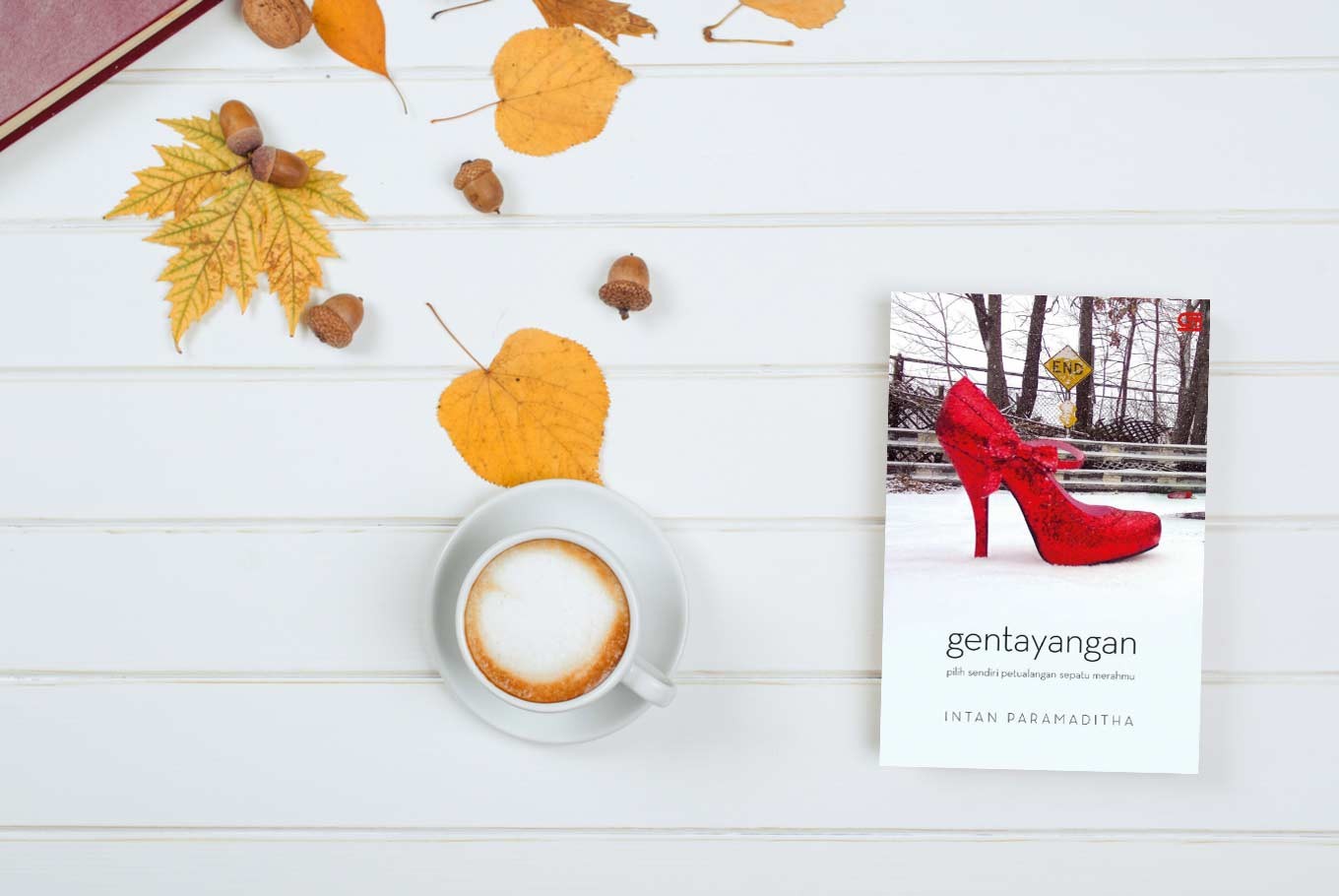

View all search resultsIntan Paramaditha's 'Gentayangan' crosses many borders

Written in the style of a choose-your-own adventure novel, Intan Paramaditha’s latest book Gentayangan: Pilih Sendiri Petualangan Sepatu Merahmu (The Wandering: Choose Your Own Red Shoes Adventure) hands you a pair of pretty red shoes and sets you free to roam the earth.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

Y

ou yearn to travel, but never have. It’s too expensive, so you’re stuck here — in Indonesia, at your boring job teaching English, despite never having stepped foot in an English-speaking country. You’ve tried to find fulfillment in romance, but your boyfriends have all been losers.

Meanwhile, your sister’s doing well: she has a successful husband, two cute kids, and runs her own Islamic fashion business. That’s fine for her, but it’s not the life you want for yourself. Not at all.

What choice does a gal have but to cut a deal with the devil? So that’s exactly what you, the protagonist of Gentayangan, do.

Written in the style of a choose-your-own-adventure novel, Intan Paramaditha’s latest book sets you free to roam the earth, from New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles, all the way to Berlin, Amsterdam and Tijuana.

Take into account the panoply of racially and culturally diverse characters, not to mention the stories of their own wanderings, and the ground covered multiplies severalfold: Lebanon and India, the Philippines and Vietnam, Belgium and Peru — the list goes on and on.

Based on these details alone, it would be easy to mistake Gentayangan for an uncritical paean to cosmopolitanism and the liberty it grants. Yet that is precisely what Intan’s novel resists.

Besides the professors, journalists and expatriates who trot the globe freely are the refugees, illegal immigrants and impoverished students who find that border crossing comes with strings attached: homesickness and solitude; poverty and vulnerability; the threat of deportation, or conversely, being stranded.

Only when the reader dons the red shoes of global nomadism does she realize their blessing and curse. On the one hand, they empower, like Dorothy’s ruby slippers in The Wizard of Oz. On the other hand, they render the wearer powerless, like the red shoes of Hans Christian Andersen’s tale.

The novel itself slyly acknowledges that what it’s doing to the reader may be rather cruel: “fiction writers really are thoughtless, if not downright vile. They work hard at creating labyrinths, find suckers to trap inside, then sit back and enjoy their victims’ sufferings while sipping coffee and munching on doughnuts.”

The book’s choose-your-own-adventure format calls further attention to the emotional baggage world-wanderers bear. When you reach the end of one adventure and go back to the beginning to start anew, you’re not really starting anew.

Or in the words of the novel: “You wish you could wipe out your footsteps, but your shoes keep catching on something behind.” Each new road you take adds to and often overlaps with the one(s) you’ve already travelled, creating an accumulation of experiences, which in turn gives rise to world-weariness and disenchantment, even as you marvel at unfamiliar people and places, taking in new sights and sounds.

Further heightening the sense of multiple déjà vu experiences are the eerie instances where characters (including the reader) turn out to be versions of other characters —figures from other people’s stories, reincarnations of the past. A man you meet on the plane turns out to be the husband in the creepy ghost story he tells. The rat-like man you meet in the subway reminds you of someone in a spooky tale you dreamed. You yourself are more than you: you’re a murderer; you’re the re-embodiment of someone else’s long-lost love.

Familiar folktale elements also appear throughout: red shoes and deals with the devil, yes, and also magic mirrors, gnomes, witches, Rumpelstiltskin and kuntilanak (female ghosts with long hair). These compound the sense that the adventures you choose are hardly new — rather, stories repeat themselves; everything and everyone has happened before and will happen again with some adjustments. Ironically, picking your own adventure merely exposes how limited your options are. Freedom of choice is an illusion. You get to pick your poison, but that’s about it.

And yet, however each adventure unfolds, the novel consistently and strongly implies that for you, a wandering state, whatever the circumstances, is infinitely preferable to being an object at rest. Or, to put it another way, unlike Dorothy, you’d rather die than click your heels three times to wish yourself back home, or for that matter, settled down.

Interestingly enough, when your decisions lead you to marry a man — the most conventional of all conventional happy endings — you find yourself horrified, or dispassionate, or trying to convince yourself that you’re content even though you aren’t.

Gentayangan thus offers not only an incisive commentary on the cosmopolitan condition, it is also a literary vindication of the unashamedly unfettered female. The novel allows you to choose how you act and respond when faced with certain situations, but your identity is fixed: a single, childless brown female in your late twenties.

Whoever you are outside the novel, you must adopt this persona and thus, to a certain extent, empathize. Her point of view becomes yours. It’s you who suffers the indignity of marrying a white middle-aged man to avoid getting kicked out of the country. It’s you who tries to curb your annoyance when your well-intentioned sister forwards you sermonizing religious email messages.

Gentayangan crosses many borders: the borders between countries and individuals and stories; the borders between reader and character and writer; the borders between “you” and “me.” And in doing so, the novel exhorts us not to be scared to step out of the comfort of our narrow minds and circumstances, no matter what lies beyond.

As the novel says at one point through one of its characters (either “you” the protagonist or your companion who refers to herself as “I” — it’s unclear and probably intentionally so): “So we’re not allowed to experiment in the borderlands? . . . Of course. Of course we can. We will continue to experiment in the borderlands.”