Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsIn Alor, the death of a language

Tradition: Nick Williams (left) sits with local residents in Alor

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

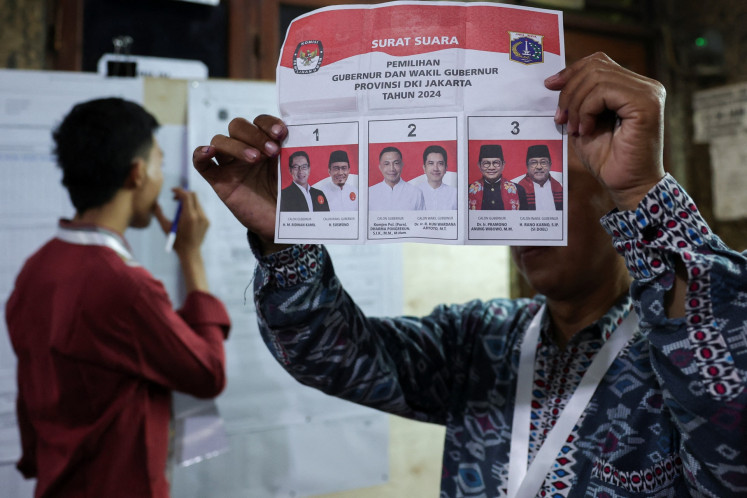

span class="caption">Tradition: Nick Williams (left) sits with local residents in Alor. Language is the main vehicle of culture, and thus identity. Kula, with its nuanced elevational distinctions, for example, gives its speakers a sense of place in the world.

On the island of Alor in East Nusa Tenggara, a language is dying ' slowly. The popular image of the last, white-bearded speaker taking a mother tongue with him to the grave is a myth. Languages go out with a whimper.

Indonesia is home to one-10th of the world's languages, making it the most linguistically diverse nation after Papua New Guinea. Of the archipelago's 706 identified tongues, nearly half are threatened or dying, according to the authoritative database ethnologue.com.

For the last year and a half, linguist Nick Williams has been documenting Kula, an endangered language with 5,000 speakers in Alor.

Kula is still used for daily communication, but it's losing users, especially among the young. If the trend continues, it will soon become moribund, with just the elderly still speaking it. By then, it will be too late.

Elderly: Kula is seeing fewer speakers among the young generation.

'The problem is that languages don't get attention when they are threatened, usually only when they reach moribund status,' said Williams during a recent interview in Jakarta.

Kula is not written, only spoken, and Williams is creating the language's first dictionary and orthography, or conventional spelling system.

To do this he has lived in the village with a local Kula-speaking family, compiling a comprehensive record of the language by recording conversations, rituals, speeches, songs and stories. It's an enormous task, but documentation is critical for preserving a language and launching revitalization efforts.

'If Kula does die, mine will be the only record,' he said.

Williams is an interactional linguist, a new school that examines how the structure of a language emerges out of everyday social interaction. Whereas most of 20th century linguistics relied on transcribing and dissecting monologue, he focuses on daily conversation and the language's functional use.

'When you look at a language in conversation, you get a more authentic idea of how the grammar works,' he said.

The structure of a language also may reflect features of the place in which it's spoken or its local geography. The Kula-speaking community lives in a mountainous area, and a large part of daily life is moving up and down hills. Thus, while Indonesian only has two verbs to indicate elevational movement ' naik (to ascend) and turun (to descend) ' Kula has several. Place is usually described in terms of elevation: A table in a room will not be 'next to' the wall, it will be 'upslope' from the wall.

Heightened awareness: The Kula-speaking community lives in a mountainous area. A large part of daily life is moving up and down hills, and the language has several verbs to describe up and down movement.

He said that generally the Kula speakers he worked with were proud of their language, but not that motivated to preserve it.

'The challenge is to get people interested. It's hard to get them to see the urgency.'

And should they? Languages are dynamic and constantly evolve and decay. Would it matter if a tongue spoken by a few thousand people on a small eastern island disappeared?

Yes, a great deal, says Williams. Since talking is the most basic social activity, language is the main vehicle of culture, and thus identity. Kula, with its nuanced elevational distinctions for instance, gives its speakers a sense of place in the world.

'Losing language is a huge step toward losing culture,' said Williams. 'If you lose linguistic diversity you're losing Indonesian identity itself ' Bhinneka Tunggal Ika. We're going to end up with this Taman Mini version of cultural diversity in Indonesia, where for all of East Nusa Tenggara you have one little display.'

Yanti is the director of the Center for the Study of Language and Culture at Atma Jaya University in Jakarta, which operates alongside the German-based Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

'We are so rich with these languages, but many generations from now we will end up with only a few,' she said.

Her work has been on the other end of the archipelago in Sumatra where a bundle of languages grouped as Jambi-Malay are also dying, but in a different way than Kula.

According to center linguist Tim McKinnon ' who lived in a village for nearly a year and a half documenting a variety called Kerinci ' these isolated Jambi-Malay communities have been experiencing increased exposure to what are considered 'higher prestige' varieties, such as Minangkabau in the market or Jakarta Indonesian on TV. Also Malayic, these languages are gradually overtaking the local varieties without speakers realizing assimilation is occurring, he said.

Though quiet, the death of these languages will have immense repercussions on their cultures. 'Entire oral literatures will be lost, along with knowledge about traditional medicine, plant and animal classifications and how to build certain things,' McKinnon said.

This process of assimilation is happening across the archipelago. According to McKinnon several linguists 'have found convincing evidence that even Indonesia's largest local languages are threatened by a shift to Indonesian'.

Even Javanese, the country's most spoken language after Bahasa Indonesia, is losing users as fewer parents teach it to their children.

'Parents assume that raising their children in their local language will somehow prevent them from learning more economically beneficial languages, like Indonesian and English,' said McKinnon. 'This simply is not true. Children can become fluent in several languages. Throughout the history of the Indonesian archipelago, multilingualism has been the rule rather than the exception.'

Despite some limited national efforts to support local languages by the Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) and others, it hasn't been enough.

'Indonesia is at a point where it needs to do something aggressive about it,' Williams said.

He suggested a good place to start would be having elementary school in rural areas taught in the mother tongue. Hawaiian and Maori in New Zealand have been successfully preserved this way ' but both with

robust state support.

'It's a massive effort. You need to standardize the language, you need educational materials in the language, you need a grammar. Most mother tongues don't have those things,' he said.

Ultimately, the role linguists can play is limited.

'At the end of the day what keeps a language alive is people speaking it with their children,' said McKinnon.

'We can't force the community,' said Yanti. 'They need to decide for themselves.'

' Photos Courtesy of Nick Williams