Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsEDITORIAL: Land for the poor: What next?

If materialized, the program will benefit at least 26 million impoverished families — 56 percent of whom have less than 0.3 ha of land in this agricultural country.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

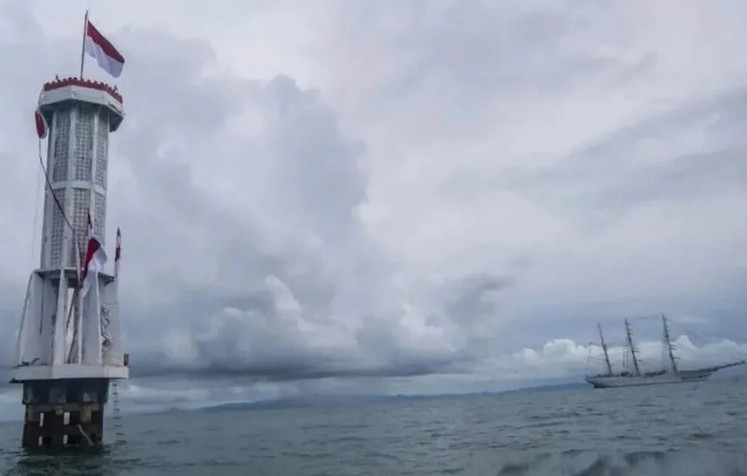

he administration of President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo is starting to redistribute state land to farmers as part of poverty alleviation measures. The measure is part of an agrarian reform program Jokowi publicly announced in his 2014 presidential inauguration speech that involves the redistribution of roughly 22 million hectares of undisputed state land — 13 million hectares to indigenous people and the remaining 9 million to impoverished farmers.

As part of the realization of the President’s commitment, the Environment and Forestry Ministry transferred land to 11 indigenous groups in December. The granted property was largely expropriated from forestry businesses whose concessions had expired. The next crucial agenda is the arduous distribution of 9 million hectares in 33 provinces, where idle land starkly differs in size and in agricultural suitability while the provinces’ populations are no less complex in terms of size and needs.

Jokowi has announced that land redistribution will start as soon as this year, with Coordinating Economic Minister Darmin Nasution saying the land will be granted to farmer associations instead of to individuals so as to minimize cases of illegal sales. Sizes of land to be redistributed will vary by region: On large but scarcely populated islands, each farmer group consisting of 30-40 families may receive about 50 hectares, while it could be much less in densely inhabited areas like Java.

Land redistribution is undoubtedly a bold program that eluded the nation in the past. If materialized, the program will benefit at least 26 million impoverished families — 56 percent of whom have less than 0.3 ha of land in this agricultural country.

The problem, however, is the fact that the 1960 Basic Agrarian Law, the legal foundation for the land redistribution program, is half a century old and has been poorly enforced and often abused, leading to widespread agrarian conflicts. In many areas, indigenous people have been evicted from their ancestral land to make way for large-scale plantations, with state representatives, such as military and police personnel, oftentimes siding with the investors. In many cases, land disputes have escalated into violence resulting in murder, forced disappearance and torture.

To support the law, many pieces of legislation will need to be made and more detailed execution technicalities defined in order to make the program enforceable. The program simply needs fundamental change in legal certainty concerning ownership and settlement of land conflicts across the archipelago.

It will certainly take a long time to complete the much-needed laws. They perhaps will be passed only after Jokowi ends his five-year term in 2019.