Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsMiniature art takes stage at Keliki Kawan Exhibition 2017

Miniature art has a long history, having been passed down over generations and dating back as far as the 9th century.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

M

ore than 60 pieces of Balinese modern-traditional art from the Keliki School of Miniature Painting went on display on April 18 at Museum Puri Lukisan in Ubud as part of the Keliki Kawan Exhibition 2017 by the Werdi Jana Kerti Artist’s Association. The exhibition in Ubud's centrally located, historical museum continues until June 3.

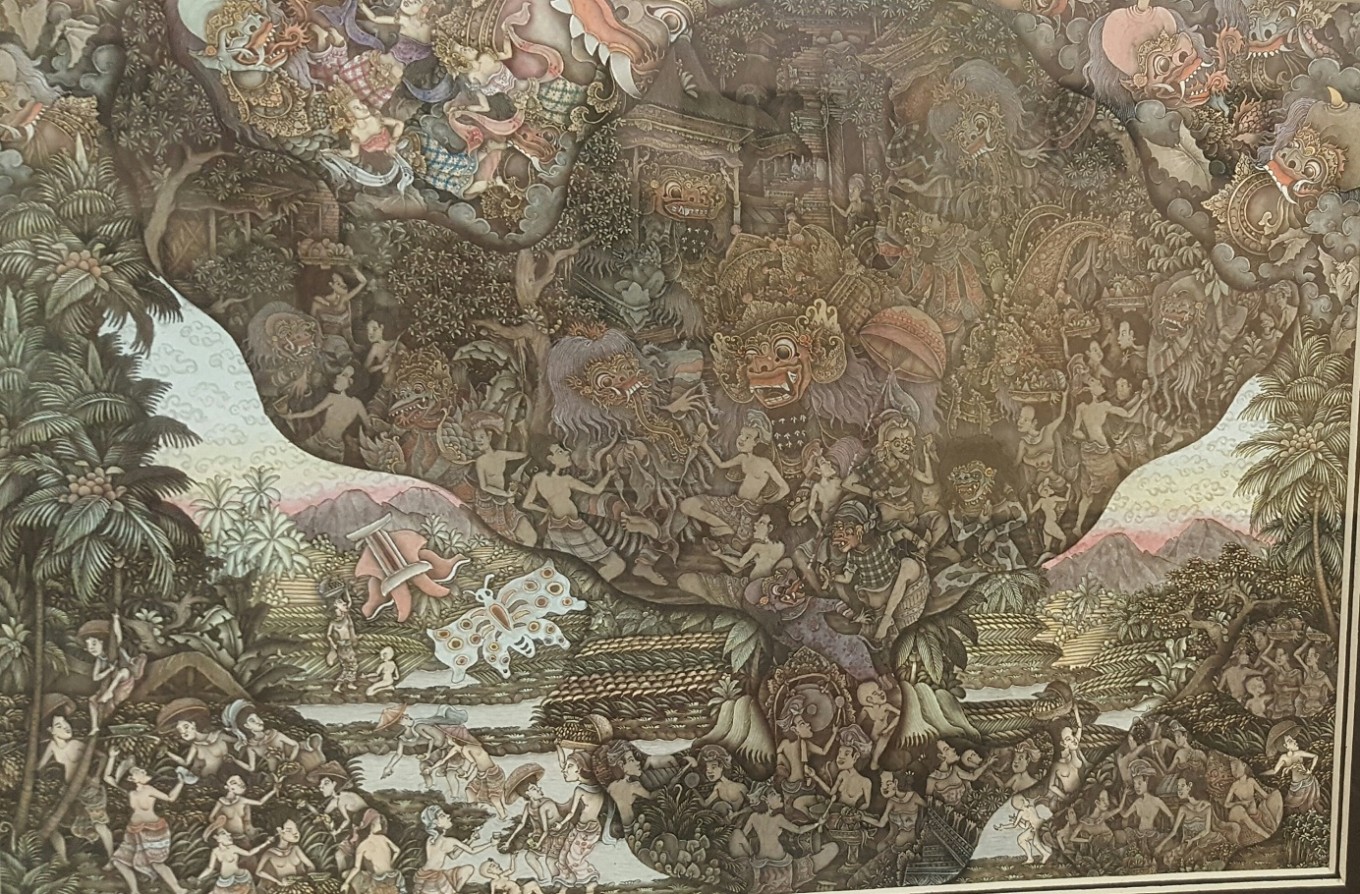

Last in line in the chronology of genres of modern-traditional art forms, coming after the mid-1960’s Young Artist’s Style, the Keliki paintings depict Balinese imagery in the tiniest of frameworks. The art of creating miniature images, however, has a long history, having been passed down over generations and dating back as far as the 9th century.

Derived from decorated manuscripts, processed on dried leaves and known as the lontars, information is contained on 30 x 5 cm pages. Still in use today, the books includes information on holy scriptures, prominent rituals, family lineages, laws, medicine, arts, architecture, calendars, literature and even cockfighting. A sharp writing instrument is used to score the small text and images.

'Panen' by I Made Jongko(JP/Richard Horstman)

'Panen' by I Made Jongko(JP/Richard Horstman)

The Keliki School of Miniature Painting opened in the early 1970’s in Keliki Kawan village, 20 minutes north of Ubud. The village today is home to more than 300 artists who adhere to a master-pupil tradition, often the father (master) and son (pupil). Two artists, I Ketut Sana (b.1952) and I Made Astawa (b.1953), are responsible for the development of this style that over time evolved to encompass a community of artists, helping to supplement the incomes of poor farmers through the sale of their work.

Both Sana and Astawa were students of the grandson of one of Bali’s most renowned artists, Gusti Nyoman Lempad (c1865-1978). They also adopted elements from masters teaching a different style at the Batuan School. Inspired by Lempad’s line techniques and the crowded Batuan style, they reduced their compositions down in size, and so the Keliki miniature style was born.

In 2011, the Werdi Jana Kerti Artists Association of Keliki Kawan village was formed in an effort to maintain and preserve the genre. Since 2013, they have showcased their work annually at Museum Puri Lukisan, a highlight on the Ubud art calendar. The collective currently has 75 members, 58 of which are participating in the current exhibition. They range in age from 14 to 70 years old -- twenty-three artists are under 30 and 11 are women.

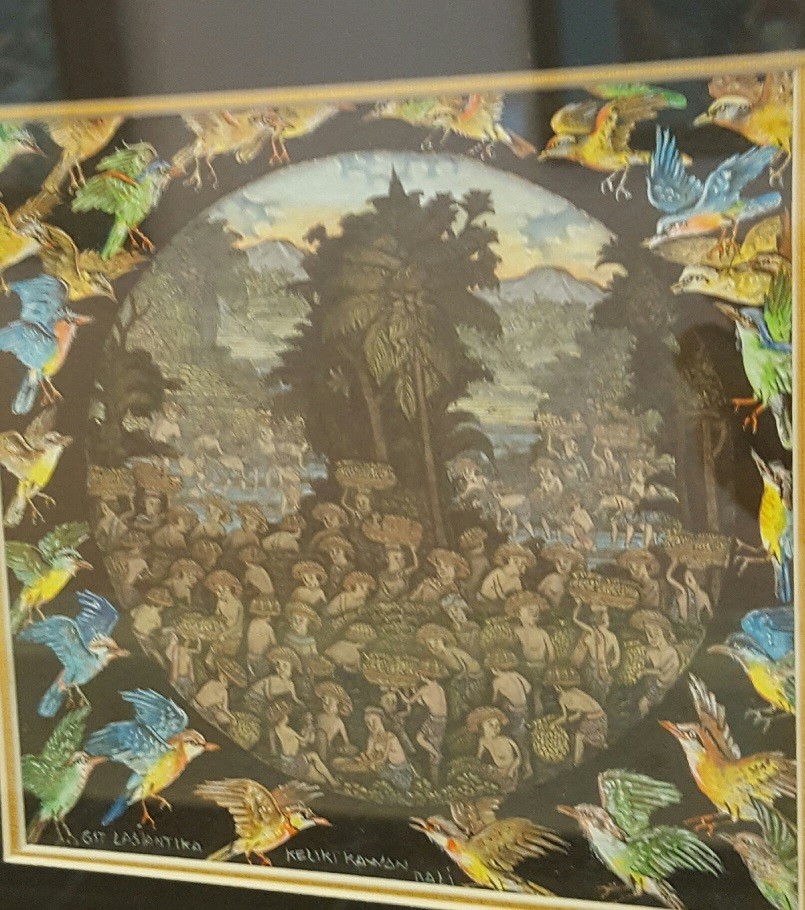

'Panen' by Gusti Putu Lasyantika(JP/Richard Horstman)

'Panen' by Gusti Putu Lasyantika(JP/Richard Horstman)

Read also: Previewing Indonesian modern & contemporary art at Sotheby’s Hong Kong spring sale

Panen, 2016, by Gusti Putu Lasyantika is a fine example of miniature-style art. The painting fuses two compositions into one. The outer image, set on a black background, is of colorful native birds peering in on the inner scenario. The birds both contrast and frame the entire piece. The inner focal landscape, constructed in receding layers to emphasize depth of field, shows farmers harvesting rice. In the distance Bali’s iconic volcanic landscape is visible with the sun’s soft golden rays illuminating the afternoon sky. What is remarkable about Lasyantika’s painting, which involved hours of painstaking attention to detail, is that all of the imagery is captured within the reduced dimensions of 12 x 12 cm.

Rapid modernization as incompatible with traditional norms has become a popular theme among traditional painters. Deforestation and relentless urban development are depicted in Illegal Logging, 2016 by Putu Kusuma. In the foreground, heavy machinery and men with chainsaws destroy the landscape. In the background, the city’s high-rise skyline encroaches. The focal point is the sacred Balinese tree as the foundation of the natural ecosystem – the tree of life.

Gusti Putu Sudarma’s Bandara Harapan, 2016, 38 x 27 cm, acrylic on paper, is also aligned with the aforementioned theme, yet his imagery is mostly unconventional. In a scene reminiscent of Dutchman Hieronymus Bosch (c.1450 -1516) and in a style that was the forerunner to the 1920’s surrealism movement, the artist depicts a composition of two opposing worlds.

The foreground is filled with colorful circus characters, both real and imagined, with an array of unusual objects, some small, others colossal. Various abstract structures and forms dominate the scene, with a few seemingly insignificant traditional parasols as the only recognizable Balinese icons.

Rendered faintly in the distance is the Bali of yesteryear -- a lush mountainous landscape is dotted with Hindu temples. The top right side depicts a small figure sitting atop a raised pillar in meditation, while the top left corner depicts two brown-toned figures -- one holds a flag in an apparent gesture of surrender, the other seems to grieve.

This is a fascinating and clever composition worthy of focused attention. Do Sudarma’s metaphoric symbols represent his idea of a dystopian Bali? (asw)

Keliki Kawaan Exhibition 2017

Open daily 9 a.m. – 5 p.m.

Museum Puri Lukisan, Ubud

Jalan Raya, Ubud, Bali