Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsObituary: Timothy Charles Scott's vibrant life

Timothy Charles Scott was a surveyor, diplomat, miner, raconteur and man armed with a wicked sense of humor

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

S

urveyor, diplomat, miner, raconteur and man armed with a wicked sense of humor. Timothy Charles Scott was all that and more during his colorful life, which was intertwined with and shaped by five decades of turbulent Indonesian history.

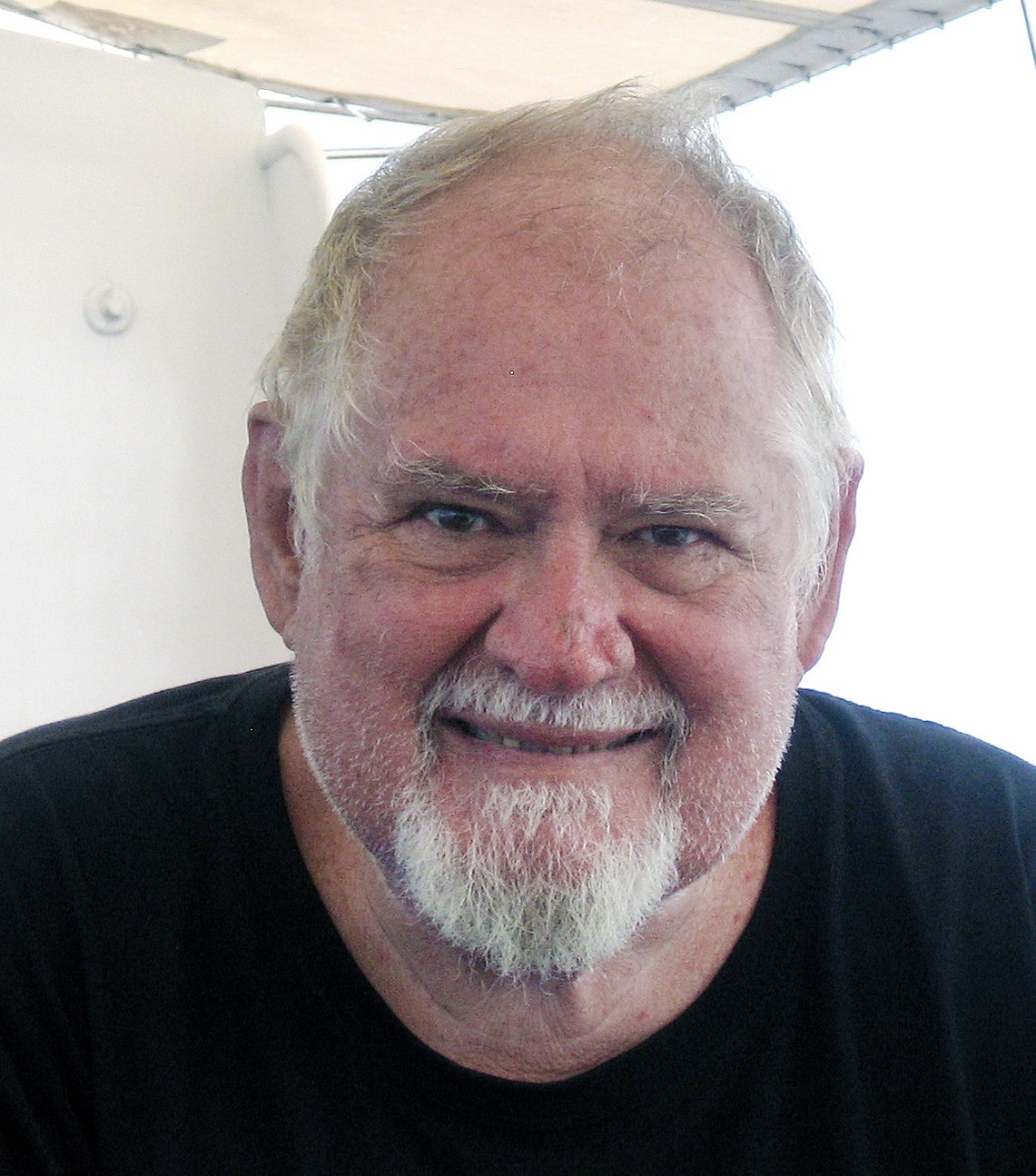

When he died at 75, the big Australian with the white goatee and sparkling eyes left behind a host of friends separated by nationality, occupation, geography and the years, but all agreed on one thing: he was a hard man to forget.

Altruistic, well-read and larger than life, always the first to see the funny side of things, he lifted the spirits of everyone he encountered with his jokes and a rich store of anecdotes about some of the central figures of the day.

He died peacefully at his home in South Jakarta on May 17 after complications from a fall he suffered a month earlier, the result of a general deterioration in his health over the past two years.

Scott was born and raised in Perth, West Australia, a descendent of early Scots sealers and Polish settlers who developed a love for Indonesia and Indonesians that was often tested, but never diminished.

Like many of the country’s most longterm expatriates, he had the depth of experience and knowledge to criticize what he saw as the failure of subsequent generations to live up to the promise and integrity of the founding fathers.

During his school years in Perth, he joined the Sea Scouts at the site of an old United States wartime flying boat base, developing a love for the sea and an expertise in explosives, on one occasion making a batch of nitro-glycerine. During school vacations, he also worked with the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) helping track emu migration patterns in the West Australian outback.

Still a teenager, Scott went to work for GSI, a mining company, amassing a lot of valuable information by buying drinks for old prospectors that allowed him to make a significant amount of money for his widowed mother. It was GSI that brought him to Indonesia in February 1963. Once here he witnessed the 1965 coup and much of the bloodshed that followed from a distance, in a jungle drilling camp at the headwaters of southern Sumatra’s Rokan River.

Among the many Indonesians he befriended in those early days was Harry Tjan Silalahi, a young Indonesian lawyer who would subsequently join the newly formed Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). Founded by economist Hadi Soesastro and brothers Jusuf and Sofjan Wanandi, the CSIS would become the country’s principal think tank and an adviser on both domestic and international affairs to president Soeharto. It was a connection Scott would learn to value.

Like a lot of young foreigners then, Scott enjoyed his first taste of Indonesia. He fondly remembered the downtown Ramayana Bar, one of Jakarta’s few watering holes, and the drunken becak (three-wheeled pedicab) races around the fountain of the Hotel Indonesia roundabout.

In 1966, he returned to Perth, where he obtained an arts degree from the University of Western Australia, using that as his entrée into the Australian Foreign Service in 1971. He cut his diplomatic teeth on postings in London and Kuala Lumpur before being sent to Jakarta as first secretary in 1976, a year after Indonesia’s annexation of East Timor, widely believed to have been given the green light by the US and Australian governments.

Over the next three years, as international criticism rained down on Soeharto’s New Order regime, he would serve as an invaluable liaison between Australian ambassador Richard Woolcott, CSIS policymakers and government agencies.

Scott also built a close relationship with then military strongman Benny Moerdani, his fluent command of the Indonesian language later allowing him to translate the bluff general’s biography and numerous other books.

Colleague David Irvine, who like Woolcott became a life-long friend, recalls that one of Scott’s greatest skills was to understand the mindset of the politically and ethnically dominant Javanese — and other ethnic groups too, judging by his grasp of Batak swear words. “He had a very deep understanding and love for Indonesia,” says Irvine, who went on to become a distinguished ambassador and head of Australian intelligence. “He could think like a Javanese, while being aggressively avuncular and overtly Australian.”

Despite decades in his adopted land, where he oversaw the building of rambling wooden house on the outskirts of Jakarta, Irvine recalls that his friend “always retained his Australianess, his common sense and down-to-earth approach.”

Scott returned to the private sector in 1981, first as country manager for Canadian explorer Husky Oil, where he worked closely with Pertamina on several innovative ventures, including secondary oil recovery.

In the mid-1980’s he had to turn back after trying to sail an old schooner from the US to Indonesia, running into a US Coastguard cutter whose captain suspected he was smuggling drugs

A second attempt almost ended in tragedy when he was caught in a typhoon off the Galapagos Islands; he managed to limp back to Panama where the boat was condemned.

After leaving Husky, Scott ventured back into mining, working for Australia’s Parry Corporation and later Canada’s Barrick Gold during the infamous US$5 billion Bre-X gold scam. The Australian had an inkling the East Kalimantan discovery was not what it seemed and he was also unimpressed with Barrick CEO Peter Munck’s efforts to form a partnership with Soeharto’s children to gain a controlling interest in the deposit.

Never one to mince words, he warned Munck he was walking into a minefield, telling him that that “going under fence” and getting involved with politically connected people to gain favors was a short-sighted policy.

In later years, Scott worked for Kalimantan Gold, a small exploration company in Central Kalimantan, and as a self-employed consultant, advising Ratu Samban Mining and Telen Indoclay, local coal and nickel miners. He also played an active part in several energy-related organizations.

After the 2004 Aceh tsunami, Scott signed on with a number of aid agencies involved in the massive international relief effort, later helping to drill water wells in other unaffected parts of the devastated province.

More recently, he assisted US and Australian diplomats looking for the graves of servicemen who disappeared in Indonesia during World War II, typical of a man who would always offer help when it was needed.

When he died, a little bit of Indonesia died with him.