'Inggris di Jawa' an alternative perspective of the British Occupation of Java

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

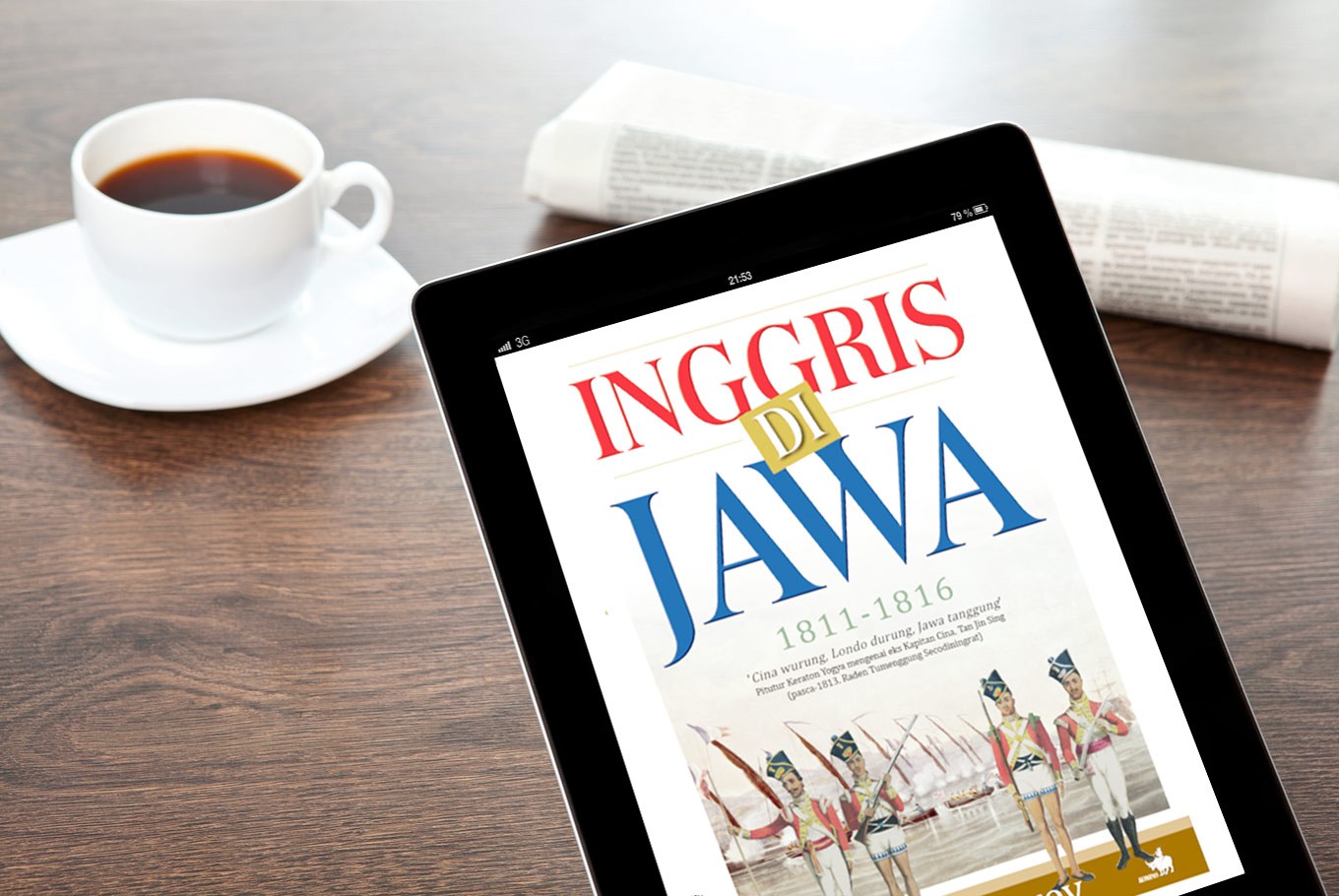

Indonesian translation of historian Peter Carey’s The British in Java, 1811-1816. (Shutterstock/File)

Indonesian translation of historian Peter Carey’s The British in Java, 1811-1816. (Shutterstock/File)

A

n Indonesian translation of historian Peter Carey’s interpretation of the British occupation of Java from an old Javanese manuscript propels us to rethink Indonesia’s position in the global world.

In conjunction with the 200th anniversary of Thomas Stamford Raffles’ seminal work The History of Java ( 1817 ), Carey, who is British, released the Indonesian translation of his book called The British in Java, 1811-1816.

The book was originally published in English in 1992 through Oxford University Press and the publisher for the Indonesian version is Kompas.

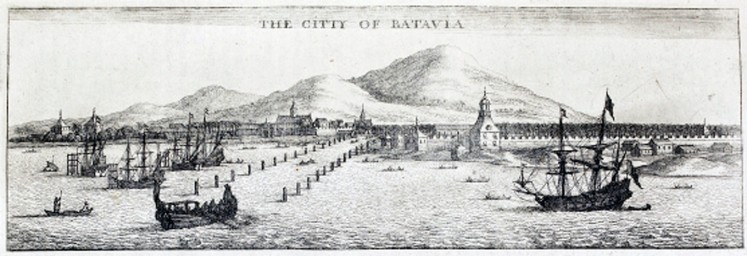

Seeking to present an alternative view of Raffles’ book, which recounts Javanese history from the British perspective, Carey’s work presents the island’s history under the British occupation from 1811 to 1816 based on chronicles written by a senior prince named Aryo Panular, who lived between 1772 and 1826.

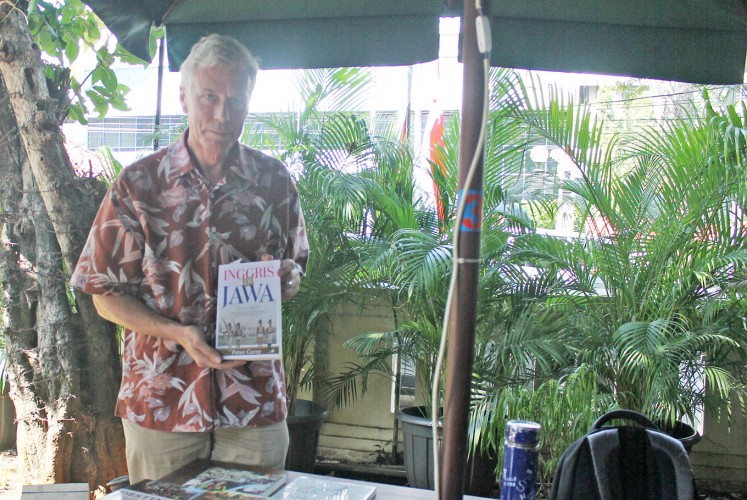

“The book is based on a very interesting manuscript by Pangeran [prince] Panular, a diary of someone living in the early 19th century, who can write every little sort of detail of life in Java at that time,” Carey told The Jakarta Post during a recent interview.

Carey added that the book would show three significant historical aspects that prevailed during the British occupation of Java at that time.

First, the period marked the first time Indonesia became involved in a global conflict. During the occupation, the British battled the French in the Indian Ocean, where the latter had control over a number of islands in what is now Indonesia.

Secondly, the period also demonstrated the significance of British naval power. The Royal Navy came to Indonesia with 83 ships and 12,000 men. For the first time, a European power was not just a force to be reckoned with commercially, but also militarily and politically. During this period, Europeans and Indonesians were also pretty much on equal footing as the former needed the latter’s help as allies.

“The [Europeans] needed to have the eyes and ears of the peranakan Chinese [Indonesians of Chinese descent] to open up local markets. There was also respect for and a certain kind of fear [on the Europeans’ part] of the Javanese, who were perceived as a warlike people,” he explained.

This has to do with the final socio-historical relevance of the book, which is countering the inferiority complex felt by the citizens of many post-colonial countries as a result of the prejudice expressed by European colonists; the book demonstrates that Indonesians are the equal of Europeans.

“In 1847, [painter] Raden Saleh visited London and he was invited to dine with Queen Victoria. In 1857, the Mangkunegara IV king composed gamelan music titled Gending Puspowarno that was later recorded for the Voyager 2 expedition,” Carey said.

“In 1916, a Javanese journalist named Sosrokartono wrote a report on the First World War in four different languages: Russian, French, Spanish and English,”

He believed that drawing from such inspiring examples, Indonesians needed to have their voice heard more on the international stage.

According to Carey, he has chosen to have his works translated into Indonesian because of a paucity of local historical texts available in local bookstores.

“You have several texts recognized by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO] as world heritage manuscripts. Yet, when you go to bookstores, you’re not going to get [ancient texts like] Negarakertagama, or I La Galigo or Babad Diponegoro, or anything to do with Panji,” he lamented.

Read also: Great Indonesian literature: Tales of Panji

He said that this happened because Indonesian culture insufficiently valued or engaged with texts. He added that this was a pity as ancient texts actually served as a foundation to form a secure and strong national character.

“In the United Kingdom, for instance, [the works of William] Shakespeare and [Percy Bysshe] Shelley are required reading in schools. Over time a situation develops in which the texts become part of how your brain works. Here [in Indonesia], we don’t have that foundation. During the Dutch time you had books published by Balai Pustaka, but now not anymore,” he said.