Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsRemembering Soeharto's cultural violence against artists of Chinese descent

Indonesian artists of Chinese descent could not freely express their artistry due to anticommunist sentiments planted by the regime.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

P

ainter Lim Wasim’s life as an artist changed when Soeharto’s New Order regime took over Indonesia in 1967 and started a systematic and bloody purge on everything deemed as a communist influence.

Lim’s paintings used to grace the walls of the State Palace before Soeharto became Indonesia’s second president in 1967, but under the latter’s 32-year, iron-fist regime, Indonesian artists of Chinese descent like Lim could not freely express their artistry due to anticommunist sentiments planted by the regime.

To survive, they slipped into the arena of fine art oriented to the market paradigm.

“By 1980, I started appearing in public by offering flower and landscape paintings. These themes are free from political interpretations. But again, such themes were deemed faulty and criticized as commercial products,” the 88-year-old Lim said.

Soeharto and the army, with the help of anticommunist mass organizations, launched the purge on everything they deemed communist-related, including cultural works like paintings, following a foiled coup attempt allegedly conducted by the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI).

The New Order’s narrative at that time was that the PKI was backed by the communist Chinese government, and during the Cold War period, it was clear that Soeharto’s regime opted to side with the United States to fight the growing influence of communism in Southeast Asia.

On Dec. 6, 1967, Soeharto’s New Order government issued Presidential Instruction (Inpres) No. 14/1967, which banned the presence and dissemination of culture smacking of China in Indonesia.

Consequently, ethnic Chinese art and cultural figures, obviously rooted in Chinese culture, had no freedom of movement. Ethnic Chinese artists were also under surveillance for decades, while references to anything Chinese was stigmatized.

The New Order’s policy caused artists of Chinese descent to be haunted by political trauma.

As an impact of the repression, ethnic Chinese citizens had to be very cautious in rendering their creativity, so as not to be perceived by the government as part of politics.

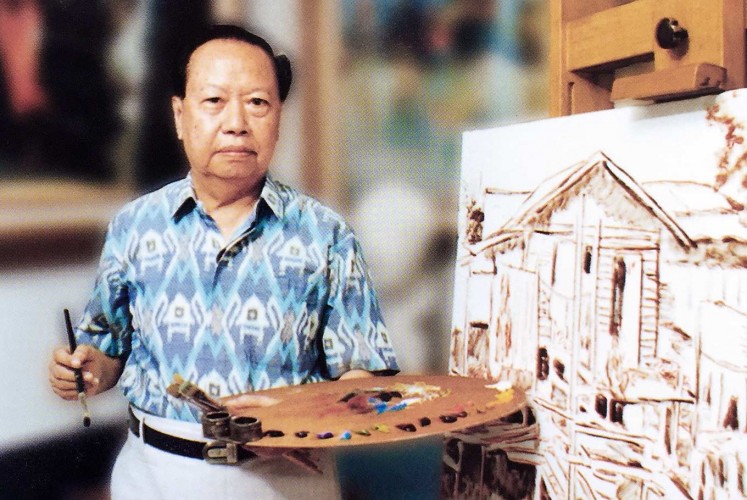

Art of survival: Lim Wasim, whose paintings graced the walls of the State Palace during founding president Sukarno’s era, poses with an early sketch of his painting. (JP/Agus Dermawan T)Nonetheless, incidents of alleged politicization of art and cases of discrimination against ethnic Chinese artists kept emerging.

In 1974, a Black December Movement appeared in Jakarta.

It was a small demonstration of young painters protesting against a decision made by the jury of the Indonesian Painting Art Biennale at Taman Ismail Marzuki, Central Jakarta.

The uproar spread to the campus where the artists studied. So, the five students of the Academy of Fine Arts (Asri) Yogyakarta were suspended.

In an interrogation conducted behind closed doors at the Asri, now the Jogja National Museum, on Jan. 21, 1975, artist FX Harsono, born Oh Hong Boen, was intensely grilled. Even his family was examined.

After questioning whether he wanted to ruin national culture and whether he realized his actions would be exploited by certain elements, it was decided to expel Harsono.

Harsono later rose to fame as a contemporary artist with an international reputation.

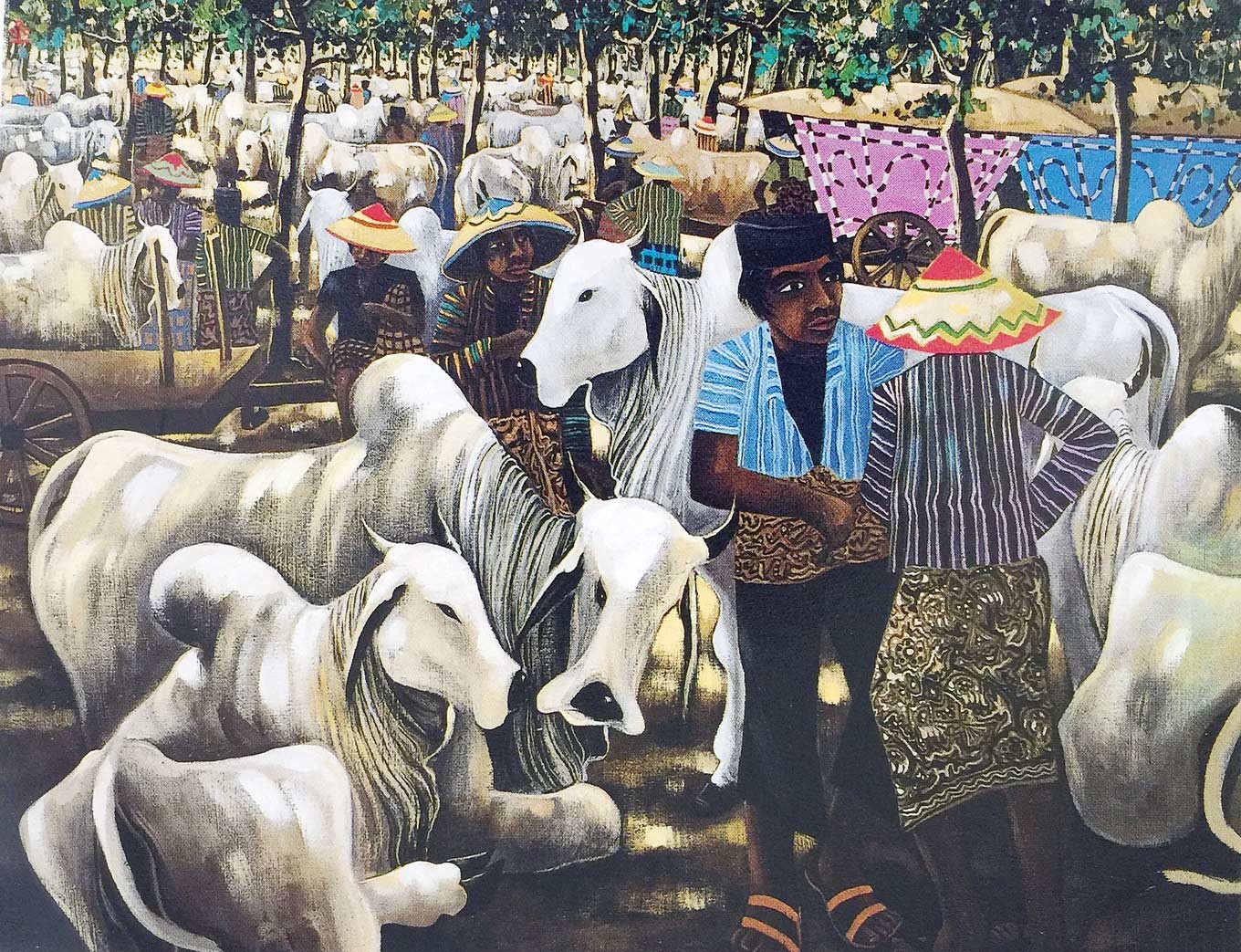

Unique touch: A painting of life in Bali by Huang Fong that features artistic Chinese influences. (JP/Agus Dermawan T)

The controversy continued, with some other students opposed to the expulsion and holding a cynical parody exhibition at Karta Pustaka, the Dutch consulate library, in Yogyakarta in March 1975, entitled Nusantara! Nusantara! (Archipelago! Archipelago!). As a result, the painters were also expelled from the school.

Undeniably, for three decades, ethnic Chinese artists were politically subjected to discrimination and later marginalization. In the 1970s in Warsaw, a museum especially dedicated to Asia-Pacific fine arts was established

Among the hundreds of paintings shown were the works of AD Pirous, T. Sutanto, Srihadi Sudarsono, Fidrus Lauw and Lie Tjoen Tjay.

The museum, which made Indonesia proud, was also reported by Indonesian journalists. But the papers publishing the news failed to mention Fidrus Lauw and Lie Tjoen Tjay, who are of Chinese descent.

Mutiara weekly journalist Ray Rizal admitted this. He was convinced that his peers had included the ethnic Chinese painters’ names, but their editors were tasked with maintaining mass media “cleanliness.”

“Editors were accountable to chief editors and they were the ones who had to deal with questions from the Information Ministry if they published articles related to the work of artists of Chinese descent,” Ray said during a recent discussion at Taman Ismail Marzuki.

Several years after the mass rehabilitation of communist political detainees in 1978, over a dozen non-political ethnic Chinese painters tried to gather and display their works at Balai Budaya, Central Jakarta.

The exhibition was an unwelcome event. It was even cynically written by a paper as an arisan (social gathering) of Hoa Kiau (Chinese foreigners), thus prompting a close watch by the State Intelligence Coordinating Agency (Bakin).

The artists also felt some alienation. In fact, the Broad Outlines of State Policy of 1978 mandated equal recognition of indigenous culture and the ethnic Chinese culture.

The discrimination continued, even expanding to different areas. In the selection of visual aspects, art characterized as Chinese paintings would rarely be allowed to join government-sponsored art programs for being seen as a manifestation of a “national enemy” and presenting a foreign vision and aspiration stemming from Chinese communism.

Actually, it is recorded in China’s modern art history that Chinese paintings were also victimized by the Cultural Revolution of Mao Tse Tung, who wanted paintings with revolutionary realism.

Inevitably, the New Order’s only government program that displayed Chinese paintings was the sixth Painting Art Biennale of the Jakarta Art Council in 1984, which showcased the water colors of ethnic Chinese artist Lie Tjoen Tjay.

No such story was ever heard afterward.

Meanwhile, such discrimination was accompanied by the ban on TV broadcasting of fine art events presenting the works of artists allegedly involved in the People’s Cultural Institute (Lekra), an affiliate of the now-banned PKI. In this context, ethnic Chinese artists were evidently equated with those of Lekra.

The repression even further covered graveyards. In 1990, the Bandung regional administration ordered the removal of Chinese characters beautifully carved into gravestones in the local Chinese cemetery. However, the outrageous instruction was later revoked.