Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsEssay: Saving the mother tongue by not cutting the foreign tongue

To respect linguistic diversity, it seems that saving and protecting students’ mother tongues should not necessarily imply cutting the foreign tongue students are speaking.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

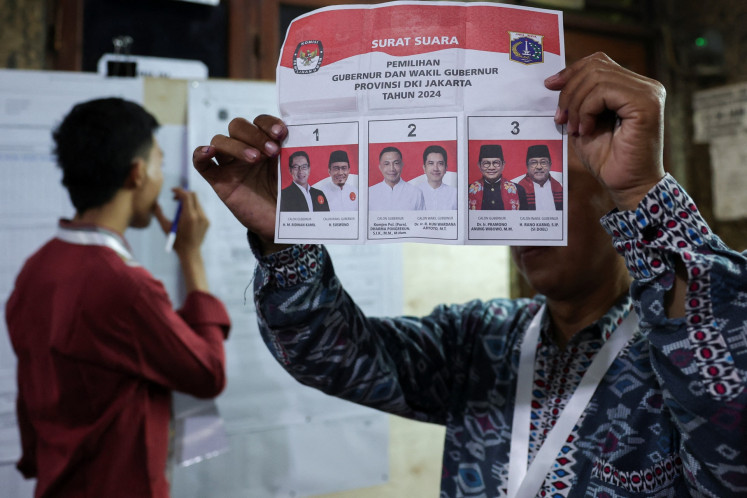

UNESCO declared Feb. 21 International Mother Language Day in 1999 to bring value and respect to linguistic diversity.

Concomitant to this year’s 70th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, UNESCO has reasserted the significance of being faithful to using one’s mother tongue and clinging to the “no discrimination can be made on the basis of language” dictum.

The cause of concern undergirded in this declaration is the very reality that most local languages in the world are facing a serious threat of endangerment and even extinction. These indigenous languages are often suppressed in their use, as their speakers abandon them, don’t pass them to their offspring or shift to other languages they consider more prestigious and modern.

In Indonesia, for example, and as in other multilingual countries in the world, many of these languages are on the brink of extinction or in a moribund state, at best. It is feared that many more local languages are no longer spoken by the people, and will become extinct in the years to come.

Responding to the threat of linguistic diversity, Audrey Azoulay, UNESCO director general, recently pointed out that “A language is far more than a means of communication; it is the very condition of our humanity. Our values, our beliefs and our identity are embedded within it. It is through language that we transmit our experiences, our traditions and our knowledge. The diversity of languages reflects the incontestable wealth of our imaginations and ways of life.”

Language then goes beyond the idea of a medium of interaction. It is not simply a tool with which we communicate both orally and in written form. Rather, it is an ideological entity or construct — the constellation of beliefs and traditions held by the individual speaker. It is loaded with values and interests, and therefore isn’t value-free. So to speak, the claim of language neutrality becomes a moot point.

Nevertheless, reality speaks louder than lofty ideals. The phenomenon of language contact facilitated by the rapid flows of people, goods and technology always implies language contestation, eventually leading to the perception of superiority, dominance and even language hegemony.

Amid the other flows mentioned above, the techno-space (to borrow anthropologist Arjun Appadurai’s coinage) has ineluctably powerfully shaped the way people use language, which leads either to language denigration or language resistance, depending on their attitudes toward the language used.

Positive attitudes toward a language can make people valorize and admire it. By a stark contrast, negative attitudes tend to render a language less prestigious, uneducated, primitive, obsolete and nonstandard.

I had the chance to meet a colleague who lamented that most of his students no longer wanted to speak their native languages in their hometowns, and shift to either Indonesian or English, which they perceived higher in status than their own home languages.

This is just a handful of instances of how language users valorize one language over another. Another example can be seen from the influx of foreign language terminologies, like those in English, flooding social media. Indeed, using English-sounding words on such a site may bring intellectual satisfaction to the users, as people associated with this language will be perceived as more educated and modern.

From the language ecology perspective, the unbridled use of English and other dominating languages have the potential to disrupt the ecology of other languages. As such, language protection is felt necessary to safeguard certain languages from this disruption.

Amid the threats to linguistic diversity, UNESCO has also endorsed the so-called the mother tongue-based education, the goal of which is to protect peoples’ mother tongues from the disruption of dominating languages. The idea is to raise people’s awareness of the importance of preserving and maintaining their own languages as one of their cultural heritages.

The anachronistic perspective of the notion of globalization, however, demands that the linguistic flow find its epicenter in the West, thus rendering English as the world’s powerful lingua franca.

It may seem natural to witness the rapid spread of English like a wildfire in almost all life domains, because this language has served not only as a lingua franca but also as a lingua cultura and a lingua academica. The language has seeped easily into local cultural products and education domain, for the West is still the locus of globalization.

Consider, for example, our fetish about aping foreign brand products in such domains as food, fashion, advertisement and beauty products. Further, our scholars heavily rely intellectually on the production of knowledge from Western countries. All these apparently wield significant influence of English as the hegemonizing language.

Language conservation through mother tongue-based education should by no means fall into the trap of conservatism or the ideology of purism, with monolingualism being the eventual goal. It should not aim to instill into students a hawkish attitude toward the teaching of English in school.

Rather, such education needs to equip students with the ability to dexterously shuttle among languages at their disposal. Multilingual education ought to raise students’ awareness of their rich linguistics repertoires, agency and identity; more importantly, it must empower students with communicative strategies that can help them appropriate other languages to suit their communicative purposes.

To respect linguistic diversity, it seems that saving and protecting students’ mother tongues should not necessarily imply cutting the foreign tongue students are speaking.

— The writer teaches at the Graduate School of Applied English Linguistics, School of Education and Language, Atma Jaya Catholic University, Jakarta.