Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsStarting with monitoring

Cattle ranching: The Brazilian National Institute for Space Research reports about 70 percent of the country’s Amazon goes to pastures, where an average of one cow grazes on a hectare of pasture per year

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

C

span class="caption" style="width: 398px;">Cattle ranching: The Brazilian National Institute for Space Research reports about 70 percent of the country’s Amazon goes to pastures, where an average of one cow grazes on a hectare of pasture per year. Courtesy of Edson Sano/Embrapa

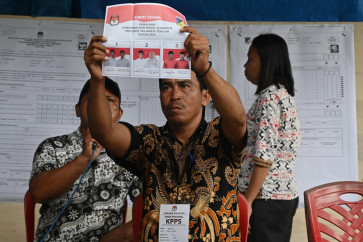

Brazil and Indonesia. What do the two have in common? Both are developing countries complete with the classic problems of social and economic gaps, boast large population of about 200 million (190 million for Brazil and 230 million for Indonesia), and have vast tropical rainforests that are being hacked away with a vengeance.

The two countries also have a litany of sound environmental laws that are largely disregarded. However, there are some key differences, and one that is important is monitoring deforestation.

Brazil has monitored land use change in the Amazon rainforest, which covers 40 percent of the country's territory of 8.5 million square kilometers, since 1988.

The National Institute for Space Research (INPE) in Sao Jose dos Campos has released an annual report on deforestation called Prodes, which is developed from satellite images that are relatively high in resolution but low in frequency.

Destruction evidence: The four pictures show Amazon forest in the process of deforestation. Farmers slash and burn forest to make way for pastures. Courtesy of National Institute for Space Research

More recently, since 2004, the institute has also released a monthly "alert map" called Deter (Deforestation Detection in Real Time), which uses moderate-resolution images from NASA's Modis (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) satellite.

While lower in resolution compared to the images used for Prodes, the Deter images are more frequent, allowing for monthly reports.

Dr. Jean Pierre Ometto, an associate researcher at the INPE Earth systems department, says identifying degradation is harder than confirming burned forest at the end of the dry season.

"There is slash and burn, and there is progressive degradation," he says. "First they cut the trees, the good wood is extracted from the forest, and then slowly they cut the area in half."

Ometto adds these phases of degradation are important in confirming deforestation.

When a plot of forest is being degraded, politicians can still say the plot is a forest, for there are still trees. But Ometto says, based on the INPE's years of observation, chances are the plot will eventually be deforested in four or five years.

He says there have been problems with regional leaders who are alerted by Deter of confirmed degradation but refuse to take action.

"Once we had to go to the location and take photographs from a helicopter. Then the governor believed us," Ometto says.

Nevertheless, the monitoring system, both Deter and Prodes, is crucial in Brazil's efforts to scale back deforestation.

Deter is useful for immediate action. The Brazilian Institute of Environment and Natural Resources (Ibama), a body connected to the ministry of the environment, use the reports to take action. "Deter allows us to act promptly on deforestation," says Ibama environmental analyst Pedro Ferraz Cruz.

Ibama has about 15,000 officers equipped with cars, helicopters and boats to help in their operations. They also work closely with public prosecutors, who have their own office in the Ibama building in the capital, Brasilia.

"We deal with administrative sanctions for violators," Cruz says.

The latest data shows that this year, Ibama has collected US$1.7 billion in fines.

Prodes, on the other hand, is more useful for policy making and other long-term purposes. The reports are widely used by both the government and NGOs.

Most people who have concerns about Amazon deforestation can rattle off by heart the ballpark figure of the INPE's 2008 data on new deforestation: 11,000 square kilometers.

Last year, the INPE reported 11,200 square kilometers of new deforestation, excluding degradation, which is harder to confirm. The deforestation reports include not only how much land has been deforested, but also where and who caused it.

"The figure showed the amount of forests that were clear-cut from August 2007 to July 2008," Ometto says. "More than 70 percent of the deforestation was due to pastures."

He adds the Prodes report for 2009 will be released later this month.

Recently, newer and better news was released. From August 2008 to July this year, deforestation dropped to 7,000 square kilometers.

Knowing how much, where and who the culprits are becomes a foundation for public policy on the environment, Ometto says. Although politicians might argue over forest degradation, the reliable and confirmed Prodes reports give little room for the decision makers to deny deforestation is taking place.

Civil society in Brazil also has its own deforestation monitoring. The Institute of People and Environment of the Amazon (Imazon) has developed a monitoring system using satellite images. Called the integrated monitoring approach, Imazon does not only record land use change but also law enforcement performance and compliance with regulations.

The organization then disseminates the monitoring results over their website, the mass media as well as to environmental agencies and prosecutors.

Establishing such a monitoring system is not hard, says Carlos Nobre, the INPE general coordinator.

"If they say it'll take years for developing countries to set up a monitoring system, I'd say it's not true," he says. "If Indonesia cooperates with Brazil, I'd say Indonesia needs six months to one year."

- JP/Evi Mariani