Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsBekasi sees more religious-based conflicts

Keeping the faith: Members of the Filadelfia Huria Kristen Batak Protestan (HKBP) church congregation sit under umbrellas to follow a Sunday service on Feb

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

K

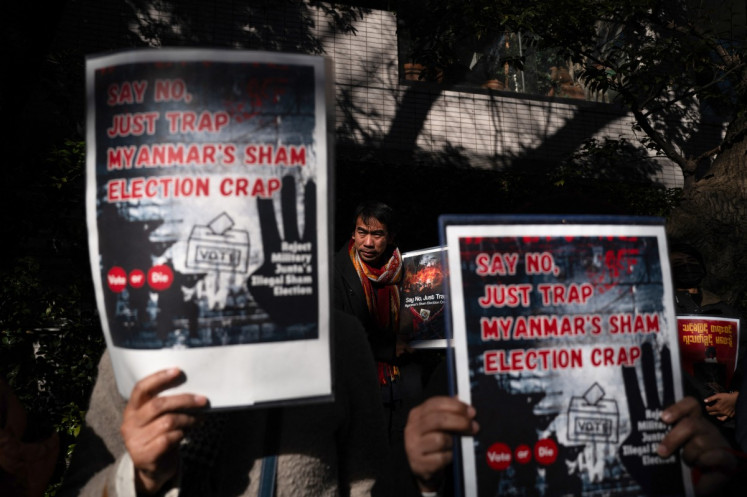

span class="caption">Keeping the faith: Members of the Filadelfia Huria Kristen Batak Protestan (HKBP) church congregation sit under umbrellas to follow a Sunday service on Feb. 7 by their sealed church construction site in Jejalen Jaya subdstrict, Bekasi. The regency sealed the site on Jan. 12 after local residents protested. JP/R. Berto Wedhatama

In a country that proudly boasts Unity of Diversity on its coat of arms, all citizens have the same duties and are granted the same rights without discrimination. For Christians in Bekasi, East of Jakarta, however, the slogan is an empty pledge as they are forced to face endless attacks and protests from local residents embracing the majority religion, over their religious activities and attempts to build a church. The Jakarta Post’s Hasyim Widhiarto tries to dig deeper into the matter and expands on it in this report.

Pretty Panjaitan, who is five-months pregnant and a member of a Protestan church in North Tambun, Bekasi, vividly remembers the day when she attended the most heart pounding Sunday service in her life last month.

“We were about to start the service when hundreds of local residents dressed in white gathered in front of our church — still under construction — and began shouting,” the 38-year-old pharmacist told The Jakarta Post on Monday. “Although police officers were able to stop them from entering our church area, I was still very scared knowing that it was impossible for a pregnant woman like me to quickly run away should violence suddenly break out.”

For nearly 10 years, Pretty and other members of the Filadelfia Huria Kristen Batak Protestan (HKBP) church have held services at each other homes. In 2007, they finally collected enough money to purchase a 1,000-square-meter plot of land in Jejalen Jaya subdistrict to build their church.

The congregation, however, never started the construction of the church as their building permit requests to the Bekasi Interfaith Communication Forum (FKUB) and Bekasi regent remained unanswered for more than a year.

In October 2009, after securing permission from Jejalen Jaya subdistrict head to hold services on their empty land, they built an 8-by-10-meter semi-permanent building to store items such as tables and chairs.

The congregation’s activities on the land, however, were met by massive protests from local residents who claimed that the congregation had no right to practice any rituals until they could obtain a building permit.

The residents, organized by the so-called Muslim Communication Forum (FKUI), then ran a series of protests each time the congregation held their Sunday services.

The forum, led by local clerics, also blamed their subdistrict head for prematurely issuing clearance for the congregation to use the land, saying the clearance was “a betrayal of the Muslim majority in the subdistrict”.

In the largest rally on Jan. 10, the group’s request to the congregation was emphatic: “Leave our subdistrict and find land somewhere else to build your church.”

Instead of facilitating dialogue between the church and residents, Bekasi regent Sa’duddin suddenly sealed off the land two days later without any notification.

“We’ve been very badly deceived,” HKBP official Tigor Tampubolon said after the sudden closure, “There has been no dialogue, despite what the Bekasi administration promised.”

Established in 1950, the satelllite city of Bekasi, which borders eastern Jakarta, has seen its trade, business and processing industries grow rapidly in the last decades, thanks to its strategic proximity to the nation’s capital and the continuous stream of investment.

In 1997, to support development, the government then split Bekasi into a regency and a municipality.

Although the Bekasi regency has an area seven times bigger than Bekasi municipality, the number of residents in each regions is about the same.

Since the more developed Bekasi municipality currently has limited space for houses, residential complexes are now mushrooming in Bekasi regency, accommodating both incoming migrant workers and commuters who work in Jakarta.

Andi Sopandi, a sociologist from Bekasi’s ‘45 Islamic University (Unisma), said the combination of rapid industrial development and the skyrocketing number of newcomers to Bekasi have inevitably brought many social consequences, including the potential for religious-based conflicts.

“Bekasi residents, especially those who live in villages, clung to strong Islamic traditions for hundreds of years,” said Andi, who extensively researched social and cultural changes in Bekasi.

“Apart from having tight social bonds, these people still strongly feel their local clerics are figures whose orders they have to follow and respect, sometimes even more than the government.”

“That’s why it has been difficult for many non-Muslim newcomers to blend with this homogeneous community or gain their full agreement over the establishment of a new house of worship.”

Source: Bekasi Regency Religious Affairs Office

According to 2006 data from the Bekasi Regency Religious Affair Office, 98.2 percent from the regency’s 1.9 million residents are Muslims.

The remaining 1.8 percent are made up of Protestants (0.67 percent), Catholics (0.55 percent), Buddhists (0.4 percent), and Hindus (0.18 percent).

The data also showed the regency had 16 churches in seven out of 23 districts.

North Tambun, where 600 of the 76,000 residents are Christians, is among 16 districts in the regency that currently have no churches.

With the limited number of churches, it is common to see Christians in Bekasi holding religious activities at homes, malls or rented buildings.

“These people are exhausted by the bureaucracy and long-standing public objections over their planned church construction. What else they can do?” Andi said.

According to a 2006 joint ministerial decree, a new house of worship must have the support of at least 90 congregation members and 60 local residents of different faiths.

It also has to obtain a recommendation letter from the Religious Affairs Office and the government-sponsored FKUB before gaining final approval from the local administration.

Bekasi FKUB deputy chief Sudarno Soemodimedjo estimated there were hundreds of Christian congregations in Bekasi regency that held religious activities outside of registered churches.

According to Sudarno, most of the public rejection to churches in Bekasi was triggered by growing perceptions that members of church congregations were “not able to build good relationships” with local residents.

“If non-Muslims residents can closely interact with the community, I think there will be no problem getting local residents to approve the plan [to build a house of worship],” he said.

“It may take years, but that is the reality that most non-Muslims in Bekasi have to deal with.”

Sudarno said that even if a church construction committee had successfully received the approval of 60 local residents as stipulated in the 2006 joint ministerial decree, the FKUB would prefer not to issue a recommendation as long as there were still public objections to the establishment of the church, however insignificant and bigoted the objection was.

“The joint ministerial decree stipulates the number of support that should be collected before building a house of worship,” he said.

“But remember, it also orders us, the FKUB, to always maintain public order, which means we have to refuse the establishment of a house of worship we believe may trigger a conflict in the future.”

List of attacks and protests against churches in Bekasi

Sept. 17, 1996

Residents attack St. Leo Agung Church in Jatibening.

Dec. 21, 1997

Hundreds attack the Tambun GKII congregation as they hold pre-Christmas celebrations.

June 15, 2008

Bekasi regency closes two homes in Jatimulya subdistrict, South Tambun, where members of the Huria Kristen Batak Protestan (HKBP) and Keesaan Indonesia (Gekindo) congregations regularly hold religious activities.

Dec. 17, 2009

Revelers marking the Islamic New Year attack the under-construction St. Albertus Church in the Harapan

Indah residential complex. Bekasi Police question 28 witnesses but arrest none, justifying the attack as “purely spontaneous”.

Dec. 25, 2009

Hundreds of residents of Jejalen Jaya subdistrict in Noth Tambun block a road leading to the construction site of the Filadelfia HKBP church, preventing congregation members from getting there for Christmas services.

Feb. 7, 2010

About 200 residents of the Pondok Timur Indah residential complex protest the HKBP congregation’s use of a house at the complex for religious services, calling for it to be stopped.

The HKBP church’s Rev. Luspida Simanjuntak tells The Jakarta Post she has received notification from the Bekasi mayor that the congregation’s church will be closed down by the end of the month.

Feb. 15, 2010

Hundreds of Muslims from 16 organizations march on the Galilea Church in the Taman Galaxy residential complex, South Bekasi, accusing the congregation of proselytizing Muslims, and threatening to shut it down.

Protest leader Murhali Barda, also chairman of the local branch of the hard-line Islamic Defenders Front (FPI), tells The Post the group will launch a crusade against churches that proselytize Muslims.