Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsView Point: Mind your (Indonesian) language!

We Indonesians are all taught at school that, “Bahasa menunjukkan bangsa” (language defines nation)

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

W

e Indonesians are all taught at school that, “Bahasa menunjukkan bangsa” (language defines nation). In the process of translating my English language books into Indonesian, I realized that our nation must be poorly defined indeed.

Last week I finally finished my third book: an updated Indonesian translation of my 2004 anthology, Sex, Power and Nation. Covering 33 years of work (1979-2012) in almost 550 pages, it wasn’t exactly a breeze. But length was not the real problem. The biggest challenge was — you guessed it — language.

Anyone who’s done any sort of translating knows the difficulties involved. It’s not just words that are being translated, but a whole state of being and thinking.

Friends have observed that when I speak in Bahasa Indonesia with my fellow Indonesians, my posture and body language changes entirely from when I interact in English with Westerners. That’s how complex and total language is.

But rather than addressing this complexity, some translators can be simplistically literal. Consider the famous howlers like “mentega terbang” for “butterfly”, “my body is not delicious” for “saya tidak enak badan” (“I don’t feel well”) or “hujan kucing dan anjing” for “it’s raining cats and dogs”. Imagine the puzzled looks of Indonesian readers visualizing dairy products with wings, or cats and dogs splattered all over the streets!

Mastering a language involves a lot, but being a good editor involves even more. Reading the definition of editorial skills I found (http://www.editors.ca/hire/definitions.html), you’d think that editors are very highly paid. Sadly, like writers, they’re not.

When I spoke to JJ Rizal, my publisher at Komunitas Bambu press (Kobam), I stopped feeling sorry for myself. What he has to face in his book business is a veritable nightmare. The problem starts with the ironic fact that it’s relatively easy to find Indonesians who speak English but much harder to find Indonesians who speak Indonesian well.

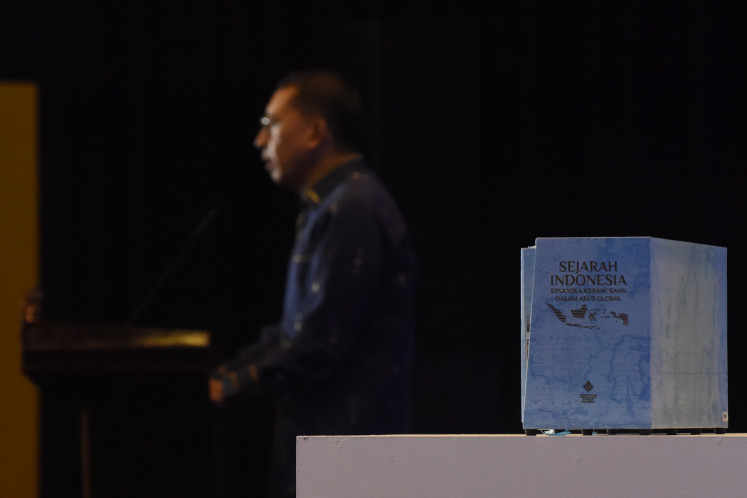

Likewise, Rizal claims the number of Indonesians who write good analysis of Indonesia — in any language! — is also relatively small. So Kobam (which specializes in books on Indonesian history and culture) is often forced to translate works by foreign scholars. It’s way more expensive, however.

Buying the rights, paying for a translator and expert editor, etc. can amount to 6 times the cost of publishing the work of an Indonesian scholar! Too often translations are done in the “hujan anjing dan kucing” mode. Yes, repeated translations and edits eventually smooth out the problems, but it’s obviously costly and time-consuming.

Much of the problem stems from our education system. It glorifies the West too much, Rizal says. Instead of instilling the mother tongue in the early school years, kids are now sometimes taught English from elementary school, with Indonesian given less time. To make matters worse, the medium for inspiring the “soul” of the Indonesian language — literary works — are increasingly less available. Appreciation of Indonesian literature is now rarely taught in schools.

This is exacerbated by the development of global capitalism and culture. Just look at supermarket ads: “boneless dada ayam” (“chicken breast”; in Indonesian dada ayam tanpa tulang), “cooked udang” (“prawns/shrimp”; in Indonesian udang matang) or “fillet ikan beku” (“frozen fish”, in Indonesian “ikan beku iris”).

This trend is also reflected in our daily language, which is full of mongrel Indoglish, words like tengkyu (thank you), seken (second-hand), konsen (concentrate), buking (booking), diskon (discount) and potokopi (photocopy).

Even pure-bred English words are appearing. It’s way more cool to use words like “part-time”, “meeting”, “update”, “feeder busway” and “image” instead of the equivalent Indonesian: paruh waktu, pertemuan, pemutahiran, bis pengumpan and citra.

Benny Hoed, one of the founders of the Indonesian Association of Translators, said the problem is that it is now considered more prestigious to speak in English: it has become a cultural reference point.

The media doesn’t help. In fact, it’s guilty of marginalizing the Indonesian language. MetroTV for example, has as the motto, “Knowledge to Elevate”. And so many of their programs have English titles: “Breaking News”, “The Golden Ways”, “Economic Challenges”, “Zero to Hero”. This is also true of Sindo and others.

Then there’s the predominance of bahasa gaul (slang). This is based on Betawi (ethnic Jakartan) dialect but has become the lingua franca of a wider community of cosmopolitan Jakartans. This is largely a reaction to the stiff formal Indonesian language developed since 1972 by the Committee for the Development of Indonesian Language in the Ministry of Culture and Education.

Understandable, perhaps, but the proliferation of bahasa gaul and Indoglish, and the resulting mixing of different levels of language (slang and formal), has contributed greatly to the sorry state of Bahasa Indonesia today.

Is the government doing anything about it? After all, Law No. 24/2009 states that “the flag, language, state symbol and national anthem, are mediums of unification [and] identity, embody the nation’s existence and are symbols of the state’s sovereignty and honor, as mandated by the 1945 Constitution”.

There is the Pusat Bahasa (Language Center), set up to guide and monitor the development of the Indonesian language. Under the leadership of people like Anton Moeliono and Amran Halim, it had some authority. But now, precisely as Indonesian is gasping for air, it seems to be doing nothing to ward off cultural erosion.

I have learned a lot from the painful process of Indonesianizing my work. My Bahasa Indonesia is definitely better than it was four years ago. Anyone care to follow my example? “If not now more when?” (in Indonesian: Kalau bukan sekarang, kapan lagi?).

The writer (www.juliasuryakusuma.com) is the author of Jihad Julia.