Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

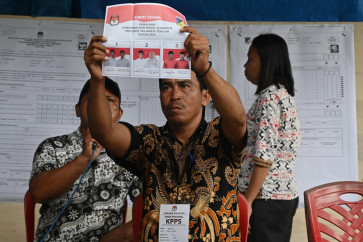

View all search resultsElectoral competition takes center stage, but lacks checks and balances

Thoughts on how to create a more efficient electoral procedure such as organizing simultaneous national and local elections are high on the agenda

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

houghts on how to create a more efficient electoral procedure such as organizing simultaneous national and local elections are high on the agenda.

To put it into perspective, however, this should be located within the overall assessment of the current state of Indonesia’s democracy.

As Oxford professor Paul Collier says, democracy has two components. One is electoral competition; but more importantly it needs to be complemented by the second one; checks and balances.

If not, it is akin to someone standing with only one leg in rough terrain. There will be no stability and various risks will always be present.

In a young democracy like Indonesia, however, electoral competition has taken center stage, overshadowing the checks and balances.

Electoral competition is about elections and, of course, elections are important. But, democracy is not merely about elections, though it cannot be less than that.

On one hand, the current state of Indonesian democracy could be described as heavy on the electoral competition element while the next required component, checks and balances, is still far from adequate.

As far as procedural democracy is concerned, the remarkable electoral reform that the country has

embarked on is mostly about electoral competition.

Political liberalization in Indonesia reached its peak with the adoption of the open-list proportional representation system in legislative elections in 2009 following the introduction of direct local elections for regional heads in 2005 for all sub-national units.

We arrived at the peak in a fairly short period of time as the country began its democratic transition officially only in 1999.

As in the case of economic liberalization, political liberalization is analogous to opening the windows and doors of your house.

While it is good for introducing fresher air circulation and gaining a better view, flinging open all the windows may not be necessarily the best option.

In a storm, the house could be damaged if it is not stoutly built. Thus care in the process of opening up while always mindful of the strength of the house’s construction and prevailing circumstances would be the wiser course of action.

As far as (procedural) electoral reform is concerned, the electoral process in Indonesia has moved far ahead of many well-established democracies.

Direct local elections for sub-national units in the UK, for example, came only in 2000 and it was not applied for all of their sub-national units. Currently there are only 16 directly elected mayoral positions in the UK, including London.

In the US, although presidents, governors and mayors are all directly elected by popular vote, in most cases partisan politics are only practiced at the state level (equivalent to provinces in Indonesia) and above, not below. While in Australia, none of these positions have ever been

directly elected.

Electoral competition in Indonesia is extremely tough. The political market for elected posts is highly competitive and increasingly expensive due to the process of political liberalization.

In the traditional economic sense, a competitive market is essentially good for consumers as the market provides them with the lowest possible prices for better quality products. A competitive market in the political sense, however, is different as it seems to have failed to provide voters or society at large as consumers with better quality leaders, let alone with lower (competitive) costs.

As a result, the following general pattern seems obvious. Once elected, in most cases (local) leaders are not responsive to the needs of voters or society at large.

Instead they primarily serve the interests of their political investors. Doing the former, if at all, serves only as a cover up for the sake of pencitraan (superficial brand imaging), while the essence is about the latter.

One might ask what has gone wrong. Nothing is necessarily wrong, the logic is that the struggle for elected political office has become very costly to win, therefore political investors are needed. If these investors are assumed to be rational agents, sponsoring potential political candidates must be seen as a wise prospective investment.

To minimize risks, an investor may even place his eggs in more than one basket by sponsoring several candidates in one contest. Spread over all Indonesian localities, elected posts form a truly competitive political market made possible through the format of tough electoral competitions.

But hand in hand with political investors comes political corruption. Such practices are widespread; this kind of democracy is not sustainable.

The problem lies in the fact that our highly competitive electoral competitions have not been perfected with adequate checks and balances. This is not to say that we do not have them.

If electoral competition, as in the case of direct local elections, is primarily about winning executive posts at local levels, checks and balances are the means to controlling it.

The role of checks and balances should be performed by the House of Representatives, regional assemblies, political parties, the media, civil society and the judicial system. Unfortunately, the noble role of checks and balances, in most cases, has been reduced to a mere (cash monetary) transaction. Instances are many.

Executives bribe lawmakers to pass bills they propose or at least to speed up the process. Semarang Mayor Soemarmo was sentenced to 18 months in jail for handing cash to members of the city council (including local party bosses) for their approval of the 2012 city budget.

Despite the growing number of independent media outlets and the mushrooming of civil society organizations since the advent of democratic transition, buying their support is still largely possible.

The same is true with the judicial system.

Against this backdrop, the performance of the Corruption Eradication Commission or KPK has been very encouraging, especially with regard to controlling and punishing political corruption. Nevertheless, public faith in the KPK dealing with (political) corruption seems to be much higher than what the commission is capable of doing.

Although the KPK has been successful in sending a number of former ministers, governors, regents, mayors, lawmakers and high-ranking bureaucrats to prison for graft, there is far too much political corruption spread all over the country.

In short, the scale and the spread of political corruption is simply massive compared to the size of the KPK with its five commissioners and 700 or so staff.

As a reminder, this country has 33 governors and around 500 regents/mayors, all are directly elected by popular vote through a very competitive and expensive process. This is not to mention the central government ministries, and thousands of lawmakers and senior bureaucrats at the central and local levels. All are prone to committing political corruption.

It should also be borne in mind that preventing and punishing political corruption is only one of the many dimensions to checks and balances.

Indonesia needs to work hard to revive the checks-and-balances component of its current democracy. Electoral competition without adequate checks and balances is only a recipe for disaster.

On a positive note, we should not forget that democracy is believed to be a system that can repair its own weaknesses. Thank God, we are there now and not returning to the bad old days of autocracy.

The writer is a lecturer in development studies at the University of Western Sydney, Australia.