Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsLegal reform ' for what?

The year 2014 is here and very soon reformasi will enter its 16th year

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

The year 2014 is here and very soon reformasi will enter its 16th year. Indonesia will be at a critical juncture: It has to make a choice between maintaining halfhearted reform without firm and strong leadership to change, or creating firmer and more inclusive governance where the foundation for a new Indonesia will continuously be constructed.

This is not an easy undertaking because once a choice is made for firmer and more inclusive governance, it would inevitably mean translating into reality expectations of a reasonably fair and just sharing of power, wealth and opportunity. A new architecture of Indonesia where all citizens can feel that they have a home, opportunities, equality, prosperity and a dream of being one nation will have to be embraced and realized.

To be fair, there have been many achievements in the last 15 years. Steady economic growth, the emergence of a larger middle class, political stability, a working democracy, press freedom, a vibrant civil society and aggressive eradication of corruption are undoubtedly products of the collective work of all elements within society. The government has been facilitating all this. However, it is difficult to deny complacency on various occasions. But we could do much better. We should be much better than we are today.

A study, The Sum is Greater than the Parts, published by the Harvard Kennedy School, describes Indonesia's economy as characterized by jobless growth, declining competitiveness in addition to rising inequality. Indonesia is not reaping the benefits of being a large country because it is a collection of disconnected local and regional markets rather than an integrated single market. Needless to say, Indonesia seems like a collection of fragmented economies.

But more than that, Indonesia is also a collection of fragmented groups of people, a plurality subverted by intolerance, harmony disrupted by the imposition of a false tune. Bhinneka Tunggal Ika (Unity in Diversity) becomes a hollow notion. We, as people, live as a nation, but a nation characterized by inequality and discrimination. We don't live in a 'separate but equal' entity, while the feeling that we are not united grows stronger, and the government seems to overlook that. Indonesia is certainly not a failed state, but it would not be wrong to refer to it as a 'fragile state'.

According to the government, inequality and poverty has been decreasing. But according to the Harvard Kennedy School study, roughly 110 million Indonesians, or around 46 percent of the population, subsist on less than the international benchmark of US$2 per day. The Gini coefficient or index on the income gap in 2011 was 0.41, while in 1999 it was 0.31, according to the Central Statistics Agency (BPS).

Therefore, it is hard to digest the meaningful success of development output. How come inequality and poverty persist despite all the good news about economic growth and investment? Achievements in democracy, even though it is extremely expensive along with our active participation in international forums, should not hide the fact that inequality and poverty are still with us. And in no single country can inequality and poverty be swept under the carpet.

Indonesia has only one choice. If we read the book by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, Why Nations Fail, we will know that sustainability, prosperity and consolidated democracy can only be achieved by having inclusive economic and political institutions. Nations will fail if they maintain extractive economic and political institutions, which result in transferring wealth and power to the elite ' the oligarchy.

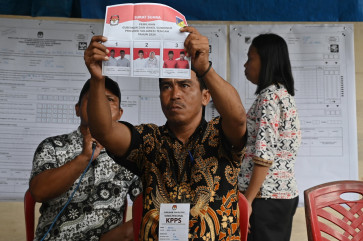

This is the critical juncture, and Indonesia has to make a choice in 2014. Thus, 2014 is not only an election year that will see a new government; it is also an election of choice: to stay with extractive economic and political institutions or to embark on establishing inclusive economic and political institutions.

At the outset, Indonesia may appear to subscribe to inclusive economic and political institutions but, essentially, it is the other way around. One foot seems to be near the inclusive economic and political institutions, while the other foot is left behind with extractive economic and political institutions.

The picture is bright but deceptive. The country has not changed that much, save for the success story of democracy and press freedom. Interestingly, if we dig deeper, we will find that our democracy is also a configuration of cartels and oligarchy. The press is surprisingly free but mostly in the hands of the oligarchy. While civil society, despite its genuine solidarity, seems to be lacking energy to fight all the way.

To embark upon establishing inclusive economic and political institutions, to firmly move from what is now called the 'middle-income trap', sharing in its broader sense is imperative. Indonesia should be a home for every citizen where equality, justice and prosperity are available and attainable.

Opportunity is a right, not a privilege. So how are we going to achieve this? The answer is simple and straightforward, that is, to have a stronger rule of law enforced throughout the country. Rule of law should be a guiding principle of our life as a nation, and this is the essence of our state as a state based on law (rechtstaat).

Compared to social, economic and political development, legal development has been rather neglected. It seems as though there has been no genuine commitment to strengthening legal institutions except in the area of corruption eradication. But what is the meaning of progress in corruption eradication if other legal developments remain stagnant, if not to say worsening? No wonder that achievement seems to be minimal because it is intended to be so.  Therefore, we should not be disappointed to see that Indonesia's Corruption Perception Index in 2013, as published by Transparency International, remains at 32, the same level as the year before. The hundreds of corrupt officials sent to prison have not changed people's perception that corruption in Indonesia is still systemic, endemic and widespread.

Therefore, we should not be disappointed to see that Indonesia's Corruption Perception Index in 2013, as published by Transparency International, remains at 32, the same level as the year before. The hundreds of corrupt officials sent to prison have not changed people's perception that corruption in Indonesia is still systemic, endemic and widespread.

Admittedly, the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) has done a great job going after corrupt officials and imprisoning them. Never in our history have we had hundreds of corrupt officials arrested, investigated and sentenced to imprisonment.

Moreover, they are also required to pay fines and restitution. This is the one point that should make us all proud. Note how many corruption cases have been handled by the KPK since its establishment in 2003. Likewise, look at how many institutions have been implicated in corruption. Imagine all these national and local lawmakers, governors, mayors, regents, ministers and directors of state-owned enterprises. In the past, under the New Order regime, these people were the 'untouchables'.

It is important to note here that these people are the ones who committed large-scale corruption, abused their power and held the state hostage. The majority of corruption comprises petty corruption, but the biggest danger for the state is 'grand corruption', where corrupt practices amount to billions of rupiah in state losses ' the cases handled by the KPK.

To be able to establish inclusive economic and political institutions, solid legislative support and endorsement are necessary. Lawmakers must have a legislative agenda that paves the way to the institutionalization of inclusive economic and political institutions.  Regrettably, the House of Representatives has been overly occupied with politicking and opposing most of the programs proposed by the government. The government has been accused of applying a neoliberal economy, but ironically the House has no alternative to offer.

Regrettably, the House of Representatives has been overly occupied with politicking and opposing most of the programs proposed by the government. The government has been accused of applying a neoliberal economy, but ironically the House has no alternative to offer.

Aside from forming an opposition just for the sake of opposing, the House seems to be merely strengthening its position and, in so doing, further weakening the unity of the state ' by endorsing the establishment of new provinces and regencies where infrastructure and human resources are not yet available. That said, all this legislation has absorbed huge amounts of the state budget, opening the way for the decentralization of corruption. Graphic 2 shows how 'productive' the House has been in its function as a legislative assembly.

Frankly, the House should have been far more productive in enacting new legislation. Sadly, however, in the last 15 years, very few legislators have been really supportive of inclusive economic and political institutions. Aside from establishing new provincial governments and regencies, the House has only managed to deliberate and pass bills concerning things that must be passed, such as the annual state budget, amendments to the state budget and various amendments to other prevailing laws. There has been virtually no new paradigm emanating from the House.

With such a low priority toward legal development by both the government and the House, there is neither coordination nor synchronization of the legislative program either at the national or local level. Therefore, it should come to no surprise that this country's legal development is in disarray. It is not uncommon to come across conflicting legislation, where one instrument undermines one or more others. Additionally, many regional and local regulations (Perda) contravene higher laws. Worse, there is legislation that supports extractive economic and political institutions, including local regulations inspired by Islamic law or sharia. This minimal appreciation for legal development, not to mention legal reform, can be seen from the state budget allocations given to law enforcement agencies since 2007. The figure averages around 10 percent of the total state budget and has in fact decreased over the years. Here, law enforcement agencies mean those directly working to enforce the law. These agencies are the police, the Attorney General's Office (AGO), the Law and Human Rights Ministry, the Supreme Court, the Constitutional Court, the Judicial Commission and the KPK. The table above highlights the budget allocations for law enforcement agencies in total.

This minimal appreciation for legal development, not to mention legal reform, can be seen from the state budget allocations given to law enforcement agencies since 2007. The figure averages around 10 percent of the total state budget and has in fact decreased over the years. Here, law enforcement agencies mean those directly working to enforce the law. These agencies are the police, the Attorney General's Office (AGO), the Law and Human Rights Ministry, the Supreme Court, the Constitutional Court, the Judicial Commission and the KPK. The table above highlights the budget allocations for law enforcement agencies in total.

If Indonesia is to embark on a journey toward inclusive economic and political institutions, toward progress and sustainability, toward realizing the dreams of its citizens, toward prosperity and the striving for a better future, it is imperative to implement progressive legal reform. The picture does not look all that bright now, but there is reason to be hopeful. We have always managed to escape from calamity ' 1965, 1998 and 2008 are testament to the fact that we are a nation of survivors. But we are approaching an inevitable and critical point, and we must pass the test. If we fail, perhaps we may not become a failed state ' but we will certainly be a fragile state.