Why Indonesia needs to borrow (a little) more, not less

Most news stories about public debt in Indonesia are quite negative in tone, portraying that increasing government debt is taboo

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

M

ost news stories about public debt in Indonesia are quite negative in tone, portraying that increasing government debt is taboo. Critics attacked the rise in public debt from Rp 1.6 quadrillion (US$134.31 billion) to Rp 2.4 quadrillion from 2009 to 2013, creating the impression that public debt is getting worse every year. On the contrary, Indonesia's public debt to gross domestic product (GDP) ratio has significantly decreased to 24 percent of GDP as of April 2014 from more than 150 percent almost one decade ago.

The ratio is far lower than most developing countries, such as Vietnam (54.9 percent), Thailand (45.27 percent), the Philippines (49.2 percent), India (67.7 percent) and most Latin American countries. The government even plans to further reduce the public debt ratio to 16.9 percent by 2020. It is not too much to say that Indonesian public debt discipline is among the strongest in the world. The steady decrease in the public debt as a percentage of GDP ratio suggests that Indonesian public debt is on a sustainable path, giving big room for more fiscal stimulus.

On the other side, many perceive Indonesian economic growth as unsustainable. Relatively high growth above 6 percent has already caused the economy to overheat, with imports rising steeply to meet domestic demand for consumer goods, basic materials and capital goods, while export revenues depend mainly on primary commodities whose prices tend to fluctuate. The economy has been driven mostly by strong domestic consumption, but production capacity cannot keep up with the strong demand.

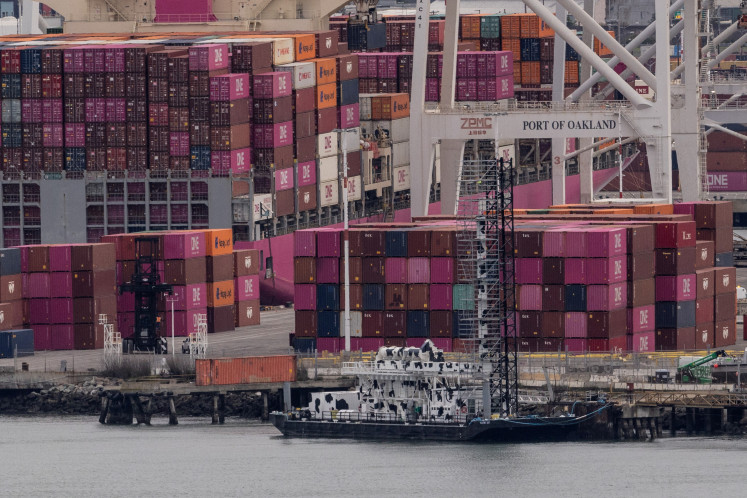

At the heart of these problems is poor infrastructure development. Average travel time in Indonesia is 2.6 hours/100 km, compared to only 1.1 and 1.35 hours/100 km in Malaysia and Thailand, respectively. Average dwelling time in an Indonesian seaport is eight days, far longer than Hong Kong (two days) and Singapore (1.1 days). Indonesian rural electrification ratio is only 32 percent, compared to 65 percent in the Philippines, 85 percent in Vietnam and 99 percent in Thailand. Other infrastructure indicators also suggest poor conditions in Indonesia, compared to regional neighbors.

One might question why Indonesia has two contradictory stories ' the story of a healthy fiscal condition and the story of poor economic and infrastructure development? One of the fundamental impediments to infrastructure development is a lack of funding for projects. The government identified the need for infrastructure investment of up to Rp 1.9 quadrillion between 2010 and 2014. However, state and regional budgets could cover only Rp 914.6 trillion of the total investment needed.

There are two reasons why Indonesia needs to raise public debt for the necessary funding. First is that many necessary infrastructure projects to develop the country simply are not attractive to the private sector. These projects, such as non-toll roads, public transportation networks, water treatment facilities and public hospitals, are called public goods.

As public goods, they do not give sufficient investment return to private investors, because the cost of provision is very high and the payback period is quite long. Hence, the government should step in to finance infrastructure to provide such public goods. If the government budget is not sufficient for such investment, it can borrow from domestic or foreign markets.

Second is that public debt, both domestically and internationally, is the cheapest way to raise the necessary funding for development. As government obligations are perceived as risk free, the cost of borrowing is far lower than that of commercial banks and equity investors. Foreign currency denominated loans from foreign government agencies are much cheaper.

The MRT Jakarta project is financed with a loan from the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) at an interest rate well below 1 percent and with a much longer maturity period than a typical commercial loan. If the government chose to finance the MRT project with private investment or borrowing from financial markets, the cost could be 10 times higher or more, and Jakarta might not be able to afford the project.

Given the importance of public debt for economic development, why does raising the debt considered taboo?

One reason is that after the Asian Financial Crisis 1997, Indonesia has been struggling to increase its credit rating, and the rating indeed has improved. Fitch Ratings finally upgraded Indonesia from Junk to BBB- in 2011. Moody's also upgraded the rating from Ba1 to Baa3, and S&P increased the rating from BB to BB+.

It is, however, interesting to observe that given Indonesia's significant improvement in the level of its public debt, its credit rating improvement has not been significant. The investment grade is still lower than that of Thailand, the Philippines, India, Malaysia and many other developing countries with significantly higher debt to GDP ratios. This is because even though we improve significantly in public debt discipline, we fail miserably in many other aspects of the economy, such as infrastructure development, fuel subsidies, bureaucratic reform and corruption eradication.

Another reason is the public perception that increasing public debt, especially internationally, equals selling the country's freedom and control to foreign interests. It is therefore politically costly to reach a political consensus on new public debt from foreign countries.

In reality, every country borrows internationally, and there is hardly any serious issue regarding national integrity arising from those borrowings. China has been borrowing heavily from the World Bank to finance its phenomenal growth, and so are other developing and developed countries around the world. The United States borrows internationally as well, and China is the US' largest creditor.

Indonesia is no different from the rest of the world. If loans can be negotiated fairly for Indonesia, it is a win-win solution. Foreign countries might benefit by providing loans to Indonesia in one form or another. But in the end, if the debt is used properly, the biggest beneficiaries are Indonesians themselves, through better infrastructure provision and economic growth.

No country in the world runs without debt, and raising debt is not necessarily a bad policy. It is important to differentiate the purpose of debt, whether it is for consumption or investment. Borrowing for the purpose of consumption will create a burden for the country.

Therefore, borrowing to finance the fuel subsidy, for example, cannot be justified. On the other hand, borrowing for investment will generate a multiplier effect for the economy, stimulate growth, create employment, increase income, generate more tax revenue in the future and finally pay off the debt itself.

Thus, what Indonesia needs is not less debt, but a better allocation of debt, shifting away from consumption toward investment. That way, more public debt can be justified for the sake of development and prosperity.

The writer is a graduate from the University of Tokyo Graduate School of Public Policy. He is currently an associate at PT Tusk Advisory, an advisory firm specializing in infrastructure delivery.