Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsSPECIAL REPORT: When Jokowi’s signature project left in lurch

The verdict is out: President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s 35,000 megawatts (MW) signature project is highly unlikely to be completely on stream by 2019, as initially targeted.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

L

ess than a month into his administration, Jokowi took many by surprise when he announced the ambitious construction of power plants to produce 35,000 MW of electricity on the sidelines of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit in Beijing, China, in November 2015.

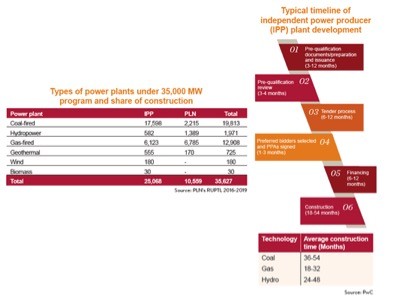

The construction of power plants to produce 25,000 MW was offered to the private sector, technically called independent power producer (IPP), while the remaining 10,000 MW went to state-owned power company PLN, which almost holds a monopoly in the country’s power business.

A string of regulations and privileges were issued to accelerate the construction and to lure more participation from the private sector, only to harvest complaints from businesses and ignite infighting between government officials.

The commotion has obviously held back the completion of the entire project, which has a 2019 deadline. Acting energy and mineral resources minister Luhut B. Pandjaitan announced in late August that only between 23,000 MW and 25,000 MW of the project could be available by 2019.

That was if, he said, the many bottlenecks plaguing the project could be immediately lifted.

.Acting energy and mineral resources minister Luhut B. Pandjaitan (left) and PLN president director Sofyan Basir. (JP/Dhoni and Nurhayati)

.Acting energy and mineral resources minister Luhut B. Pandjaitan (left) and PLN president director Sofyan Basir. (JP/Dhoni and Nurhayati)

Poor business processes and governance issues in PLN, assigned to spearhead the construction and partner with the private sector, have mostly been blamed for exacerbating the already-protracted problems inflicting those in the private sector wanting to participate in power plant construction.

As problems with land acquisition and local administration licensing processes remain largely unresolved, businesses are now being forced into another round of bottlenecks stemming from policy uncertainty.

For private companies wanting to participate in the project, red tape at PLN remains a hard nut to crack, even before they can move on to the construction phase, despite Jokowi’s repeated calls for the bureaucracy to be trimmed down to less than one year.

“In reality, it still takes years for the pre-construction process. The uncertainty remains high because the poor business processes in PLN enable it to hang up decisions without any reasonable and transparent basis,” said Indonesian Independent Power Producer Association (APLSI) executive chair Arthur Simatupang.

Arthur cited as examples PLN’s discretionary right to terminate a tender without providing transparent reasons, refusing to comply with regulations on rates and delaying decisions to sign contracts with the private sector without a rational basis.

Companies cannot enter power plant business unless they forge a contract in the form of power purchasing agreement (PPA) with PLN.

A recent study by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) revealed that prior to construction, private companies required between 19 and 43 months of paperwork, from pre-qualification preparation and the bidding process to financial closure. The construction would then take another 18 to 54 months.

Given the lengthy undertaking, Luhut has demanded PLN immediately improve its business processes to prevent more delays in the 35,000 MW project, by revising its internal regulations, among other things.

“Ideally, PPA and financial closure could be done within 18 months so that construction could immediately begin,” he said, adding that PLN was in the process of streamlining its paperwork.

Source:(PwC/File)

Source:(PwC/File)

PLN corporate secretary Bambang Dwiyanto recently acknowledged the lengthy paperwork process, and said the company was attempting to resolve the bottlenecks by forming a new directorate to deal with the issue and accelerate the PPA process.

Other attempts to speed things up, Bambang said, included bidding process acceleration for steel procurement, recruitment of 1,000 auditors and cooperation with the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) to monitor the process.

But resolving the red tape would not guarantee continuity as subjectivity was also at play. For example, PLN unilaterally terminated in June the bidding for the coal-fired 2 x 1,000 MW Jawa 5 power plant in Serang, Banten, among the largest in the wider 35,000 MW project, citing problems with “good governance”.

Imbued with discretionary rights, PLN recently directly appointed its subsidiary PT Indonesia Power to construct the US$3 billion plant in cooperation with a Japanese company in a bid to reduce China’s role in Indonesia’s power plant construction, PLN president director Sofyan Basir said recently.

“The direct appointment is aimed at accelerating the construction. Open bidding would take time, and we’re in a hurry to meet the 35,000 MW deadline,” said Sofyan, former state-run Bank Rakyat Indonesia (BRI) president director who took PLN’s helm in December 2014.

PLN’s direct appointment privilege has annoyed Luhut, arguing that it would go against good governance, as campaigned for by PLN. “That’s not the way things are done. The project is subject to open bidding for transparency and fairness,” he said.

As Indonesia’s biggest state company by assets, PLN is often mired in governance issues, with many of its officials in the past having ended up in prison for graft.

The resignation of PLN president commissioner Kuntoro Mangkusubroto, a figure of high integrity, in May positioned PLN in the governance spotlight amid political tussles between Sofyan and then energy and mineral resources minister Sudirman Said, who accused PLN of a series of foul plays.

State-Owned Enterprises Minister Rini Soemarno cited the resignation as being due to personal reasons.

But several sources have suggested it was more about governance issues as Rini has clipped the authority of PLN’s board of commissioners, stopping them from participating in the recruitment of the company’s executives and from having any decision on power purchasing agreements with PLN’s private partners.

A dissenting chain of authority over PLN has also complicated decision making in the 35,000 MW project.

By regulation, the PLN president director has two direct superiors: the energy and mineral resources minister for policy and the state-owned enterprises minister for performance, with the authority to dismiss and retain the boards of directors and commissioners.

Sofyan explained that the firm had a responsibility to both ministers, and demanded they not issue regulations without regard for business interests and the company’s profitability.

Amid the protracted bottlenecks in the 35,000 MW project, PLN seems to being pinning success on instant mobile power plants (MPPs), which are supposedly fueled by gas but in most cases are run on expensive diesel fuel.

Procurements for MPPs are direct appointments, taking less than six months to become operational. According to PLN’s 2016-2019 business plan for electricity provision (RUPTL) issued in June, around 4,000 MW of the company’s allocation in the 35,000 MW project is in the form of MPPs.

Source: (PwC/File)

Source: (PwC/File)

A gas-or-diesel-fueled 100 MW MPP for the backwater province of Gorontalo was the first of the 35,000 MW project to be officiated over by Jokowi in June.

As of Aug. 18, only 195 MW (all in the form of MPPs), or 1 percent of the 35,000 MW project, were already in operation, while the remaining 22 percent were under construction, 29 percent were in the procurement stage and 21 percent in the planning phase.

Around 27 percent of the project has yet to start construction, although the contractors have signed PPAs with PLN, according to a PLN presentation.

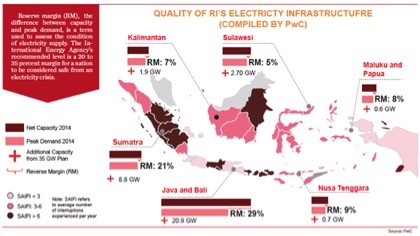

The 35,000 MW project is basically a continuation of the 10,000 MW policy launched by then-president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono in his first term as president in 2005, to keep reserve margins — the difference between capacity and peak demand — within the International Energy Agency’s recommended level of 20 to 35 percent.

As the nation is at risk of a power crisis should the level decline to below 20 percent, Jokowi has taken the initiative to boost power capacity to accommodate higher economic growth. Reserve margins for the Java-Bali grid currently stand at over 30 percent, according to PLN.

Of the 35,000 MW, only 18,000 MW are actually new projects offered to private investors, according to PLN data, while the remaining 7,000 MW are a carryover from Yudhoyono’s term, and 10,000 MW are PLN’s share.

Last year, PLN inked PPAs for 9,780 MW, while only 300 MW were agreed between January and July this year. The government is targeting PLN seal PPAs for 11,730 MW by the end of this year to prevent more delays to the ambitious project.

Energy expert Agung Wicaksono, former member of a government unit tasked with overseeing the 35,000 MW project, doubted whether PLN would able to complete the task since it would need greater efforts than last year’s to complete the PPA within less than six months.

“On top of that there are credibility and governance issues plaguing the company. Given the many policies at PLN that have created business uncertainty, there is growing distrust in the market on how this project is going to be managed,” said Agung.

What’s the chance of Indonesia facing power crisis?

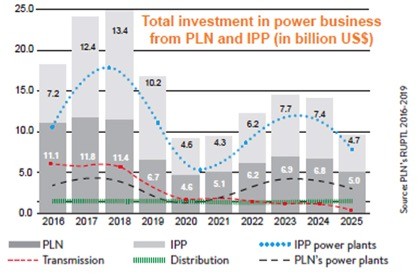

Source: (PLN/RUPTL 2016-2019)

Source: (PLN/RUPTL 2016-2019)

Despite the 35,000 MW project likely to miss its mark of all plants being operational by 2019, Indonesia is unlikely to suffer an electricity crisis, at least before 2020.

Low demand for electricity following sluggish economic growth and ample supply from new power plants coming on stream are cited as among the reasons power crisis will remain at bay.

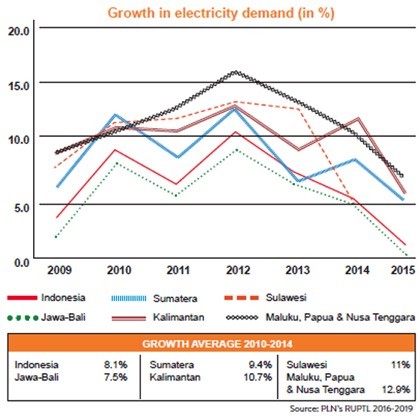

The ambitious 35,000 MW project was convened based initially on assumptions that the economy would grow at an average of more than 6 percent per year, which translates into an increase of more than 7 percent in electricity demand per annum until 2019.

However, as the economy grew by 4.79 percent last year, demand for electricity nationwide rose by only 2 percent.

Electricity demand in Java and Bali, the country’s center of industry and growth, expanded by 0.8 percent last year, lower than over 5 percent growth initially projected.

With as much as 25,000 MW of the targeted 35,000 MW expected to go on stream by 2019, this may at some point be a blessing in disguise for state-owned power company Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN).

The delay will prevent PLN from suffering huge losses due to oversupply amid subdued electricity consumption.

The company is required to purchase the electricity produced by independent power producers (IPPs), regardless of demand.

“The delay in the project’s completion will not mean the end of the world,” PLN president director Sofyan Basir said recently.

“We want the 35,000 MW project to be completed by 2019.

But we have to be rational and recognize the fact that not all the supply can be absorbed. With the economy growing at an average of 5 percent, a supply of 5,000 MW per year would be more than enough,” he said.

Prior to the 35,000 MW program, Indonesia received an average of between 2,000 and 3,000 MW of new electricity supply per year.

High reserve margins of over 30 percent for the Java-Bali grid and the Sumatra grid also illustrated how Indonesia had kept its potential electricity crisis at bay, according to PLN.

The margin is the difference between capacity and peak demand, with the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) recommended level being a 20 to 35 percent margin for a nation to be considered safe from an electricity crisis.

“We actually have an oversupply of 30 percent, as reflected in the reserve margin. But why do blackouts still occur in Jakarta and Java? That’s because of problems in transmission,” PLN planning director Nicke Widyawati said recently.

“Transmission is critical, and that’s where PLN will pour its resources to catch up with demand,” she said.

PLN, which holds a monopoly over the transmission business, is currently constructing a network of 46,000 kilometers of transmission, slated for completion by 2019.

Aside from transmission problems, a recent study by PwC suggested uneven electricity distribution.

“The Java-Bali average reserve margin is deceptively high. In fact, the load distribution [heavy in Jakarta and West Java] versus capacity [concentrated in Banten, Central Java and East Java] still creates localized issues for the grid in Java,” said the study.

“In recent years, when the reserve margin has fallen to 15 percent, PLN was forced to implement load shedding, leading to two-three hour daily blackouts.”

The reserve margin for Sulawesi, Kalimantan, Papua and Maluku and Nusa Tenggara is far lower than the IEA’s recommendation.

Energy expert Agung Wicaksono suggested a reevaluation of the 35,000 MW project as the underlying projections that supported the ambitious project had all missed the mark, particularly electricity demand.

A failure to recalculate real demand in the next couple of years would create a burden for PLN in the form of oversupply, potentially causing massive losses to the company, which was already in debt, he said.

“This year, electricity consumption is projected to grow by 3.9 percent, far lower than the initial projection of 7.8 percent. That illustrates how all the projections have strayed away from their forecasts,” said Agung, former deputy chair of the now defunct Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry’s team for the acceleration of electricity projects.

Protection for 35,000 MW

Source:(PLN/RUPTL 2016-2019)

Source:(PLN/RUPTL 2016-2019)

After announcing the ambitious project in November 2014 on the sidelines of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit in Beijing, China, Joko “Jokowi” Widodo officially launched the project in a ceremony in May 2015 in Yogyakarta.

The project will require the construction of 219 power plants, 737 transmission facilities consisting of 75,000 towers, 1,375 main stations, 2,600 transformers using 300,000 kilometers of aluminum cable.

Investment for the project is estimated at Rp 1.1 quadrillion (US$83.6 billion).

To secure the project from recalcitrant police officers and prosecutors, a commitment was forged in September last year between then National Police chief Gen. Badrodin Haiti, Attorney General M. Prasetyo and PLN president director Sofyan Basir to provide direction for PLN officials so they could avoid making legal or policy mistakes that could drag them into being prosecuted for creating state losses.

The law enforcement agencies are also committed to not disturbing PLN officials with the threat of prosecution related to carrying out the project.

A finance minister regulation was also issued in late August, providing a guarantee for the projects.

It gives two guarantees for several projects, namely the 35,000 MW program, the construction of 46,000 kilometers of transmission lines and other supporting infrastructure.

The first guarantee is a loan guarantee, to be given to financial institutions that provide financing to state-owned PLN as loan repayment assurance.

The second guarantee is a business feasibility guarantee, to be given to independent power producers (IPPs) that partner with PLN. It is to provide assurance that PLN has the financial capacity to purchase the power produced by the IPPs according to their agreed contracts.

Robert Pakpahan, director general of financing and risk management at the Finance Ministry, said the government hoped to smooth PLN’s electricity generation journey by providing the guarantees because some of the projects assigned to the company might not be economically feasible.