Why it's important to talk about Chinese-Indonesians or Chindos

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

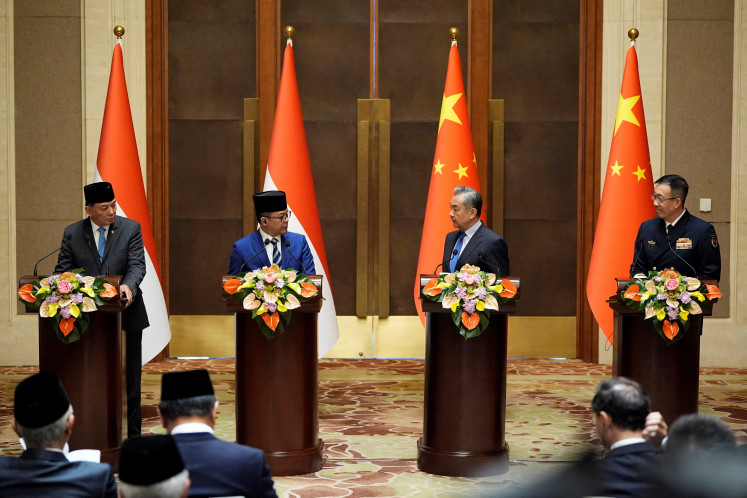

In riot: Residents gather in front of Dewi Samudera, a Chinese temple or pagoda in Tanjung Balai, North Sumatra, which was plundered and set ablaze by an angry mob on July 29. ((Courtesy of kini.co.id/-)

In riot: Residents gather in front of Dewi Samudera, a Chinese temple or pagoda in Tanjung Balai, North Sumatra, which was plundered and set ablaze by an angry mob on July 29. ((Courtesy of kini.co.id/-)

T

hroughout Indonesia’s history, there has been one subgroup that has basically always existed in its society. That is the Chinese-Indonesians, shortened to Chindos by many. When talking about them, it seems that there is always an air of discontent and discrimination.

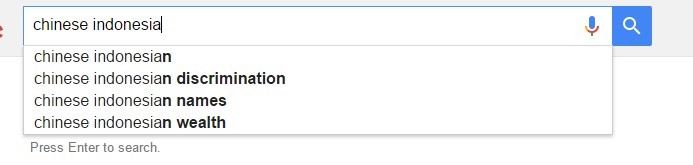

Thinking about this, I decided to run a Google search on Chinese-Indonesians, and without even finishing the sentence, I got to find out what were the most popular searches regarding the keyword:

The result suggests that Chinese-Indonesians are synonymous with wealth and discrimination. Being one myself, I decided to look into this further to find the origins and reasons for this stereotype that Chindos are supposedly richer than most native Indonesians.

The history of Chindos

To understand the mindset of Chinese-Indonesians, we have to understand the history of how they came to Indonesia. The massive migration of Chinese peoples was mostly triggered by the rise and falls of multiple dynasties in mainland China, which caused people who were in support of the previous dynasty to find refuge elsewhere. Another reason for Chinese citizens migrating to Indonesia was the exploratory nature of the Chinese people. In early 15th century one of the great expeditions led by Cheng Ho established a Chinese-Muslim colony in modern day Palembang in South Sumatra. We must remember that these were refugees and farmers just like many of the natives in Indonesia at the time.

The turning point in the relationship between the Chindos and the native Indonesians came during the Dutch colonial era. Due to the Chinese aptitude in trading and business, they became mediators between the natives and the colonizers. The Dutch split the Indonesian hierarchy into three levels with the Dutch on top, Chinese in the middle and the natives at the bottom. Although the Chinese did not get the same privileges as the Dutch, they still maintained a monopoly over trade and thus was in control of the economy from that point forward. At the same time, the Chinese felt that they were losing their national identity, caught between the Dutch and the native Indonesians. Many Chinese protested for the same rights as the Dutch in parliament. However, the two main types of Chindos we see today were probably influenced by the Cung Hwa Hui (CHH) formed in 1928 and the Partai Tionghoa Indonesia (Chinese Party of Indonesia) formed in 1932. The first sought a new type of Chinese society, which mixed elements of Dutch influence into their culture, and the latter promoted assimilation between the Chinese and the natives.

(Read also: Why Indonesians should write about Indonesia in English more often)

The modern turning point

The stereotype that the Chinese were very economically minded lasted long into the 1950s and 1960s during the regime of Indonesia's first president Sukarno. While Dutch rule kept native Indonesians to farming work, the Chinese were told to run the businesses. Therefore, once Indonesia gained independence, virtually every retail store in Indonesia was owned by a person of Chinese ethnicity. During the 1955 period, the government decided to enact the Benteng Program and the 10 presidential regulations of 1959, which imposed regulations on ethnic-Chinese rural retailers.

However, as a result of the political struggles that the country went through after the failed 1965 coup, Suharto needed growth in the economy, so during the that period the Chinese were given opportunities to promote economic growth in the country, where the next two decades would be known as a time of great economic prosperity in Indonesia with Chinese-Indonesians at its helm, expanding their businesses. In a 1995 study published by the East Asia Analytical Unit of the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, approximately 73 percent of the market capitalization value of publicly listed companies (excluding foreign and state-owned companies) were owned by Chinese-Indonesians.

Although it seemed like the Chindos enjoyed most of the economic success in the Suharto period, they did not get there without working hard. The fact of the matter is, there are many anecdotes from Indonesian nationals that the reason many Chinese are successful is because of their thrifty nature. Most Chinese people follow a concept of guan xi, which means that one’s existence is defined by their connection to others, in this case business connections. From the beginning Chinese people were more economically minded. A testimony was given on quora by an Indonesian, Ikhsan Rajab, that stated:

“As a child, I once asked my father this exact same question. He answered my question based on his anecdotal experience, which is probably not accurate, but could give some insight. His answer was: When I was just a little boy, Chinese-Indonesians were just as poor as the rest of us. They started as small businesses. But what made them able to expand their business more rapidly was because they invested heavily in their business. They gave their blood, sweat and tears developing their family business so that their family could one day live comfortably. If they earn Rp 1000, they will only use Rp 100 to indulge on their personal hobby. They will then use the rest of the money to expand their business. They were more than happy to hold off buying fancy shirts and jewelry. In short, they were willing to give up personal possessions to expand the business.”

Being a Chinese-Indonesian myself, I understand this concept more than anything. The concept of connections, success, being thrifty, always being conservative, etc. are all staples of a Chinese parent’s lecture when you get home from school.

(Read also: Defining Indonesian-ness: Power, nationalism and identity politics)

May 1998 riots

In the years before the Asian financial crisis, Indonesia’s gross domestic product (GDP) was growing at 8 percent every year under the Suharto leadership, but as soon as the crisis hit in 1997, and the Thai baht fell, so did the Indonesian economy. Economic growth staggered from 8 percent to a mere 1.4 percent in the fourth quarter of 1997. Gas prices rose 70 percent and the Indonesian rupiah dropped to one-sixth of its original value.

In an attempt to restore faith in the Indonesian economy, Suharto urged all of the richest businesspeople in Indonesia to give to a communal fund to help the economy, which merely put on display the amount of wealth and which large companies particularly Chindo businesspeople owned in Indonesia. When the riots began, the Chindos were targeted with a total death toll of more than 1000 people and 150 rape allegations by Chindo women, where to this day has left a scar on Indonesian history.

Beyond the riots, new rise of Chindo discrimination

In the last decade, due to government reform, the old discrimination is a shade of what it used to be. Until recently the burning and plundering of several Buddhist temples in the city of Tanjung Balai in North Sumatra have sparked concerns about anti-Chinese sentiments, with Indonesia’s second-biggest Muslim group, Muhammadiyah, calling for greater religious and racial tolerance. As of late, more and more riots are happening around the country because of the possible reelection of Jakarta Governor Basuki “Ahok” Tjahaya Purnama, with many saying that his policies are only benefiting Chinese tycoons.

Even after the rise of multiculturalism in the 2000s, there are still many nationalist and fundamentalist groups that have a fear that the Indonesian way of life is being threatened. This fear is rooted in the domination, politically and culturally, of the indigenous population. During the Suharto era, despite having a monopoly over 70 percent of the Indonesian economy, Chindos were kept down by the government. However, recently a different picture has emerged today. In the mind of many pribumi (native) Indonesians, the ethnic-Chinese today are making political inroads. They cite Chinese-Indonesian politicians such as Hasan Karman (former mayor of Singkawang), Christiandy Sanjaya (the vice governor of West Kalimantan), Ahok, and his younger brother, Basuri Tjahaja Purnama (former regent of East Belitung). Ahok’s wish to contest in Jakarta’s next gubernatorial election has many native Indonesians worried about their future and the continued existence of Indonesian nationalism.

(Read also: Why, despite democracy, intolerance seems endless)

In a Wikipedia page about Chinese-Indonesians, at a certain point there was a division between the Chinese people living in Indonesia. They were split between the totok and peranakan. The former refers to traditional Chinese communities that practiced their culture in Indonesia, while the peranakan were people who believed more in nepotism and had a stricter attitude towards divorce. However, the modern version of the words have changed with those who migrated from China recently are the totok and the peranakan are people who are Chinese but were born in Indonesia (the word peranakan literally means “child of the land”).

What we must realize in the end is that many new Chindos are children of this land. I have seen many in international schools who choose not to leave the country because of their pride of Indonesia. The fact of the matter is most of us come from second or third generation Chindo families, just like there are second or third generation Indian families that live here too. We were born here, grew up here and hold an Indonesian passport. We work just as hard as anyone else and if we receive success it is not because it was handed down to us.

Another fact that many choose to ignore is that there are rich Indonesian natives too, that have worked their hardest to establish connections and grow their business. In the same line of thought there are many Chindos who struggle daily to make a living with their low-paying jobs.

Indonesia is a large, developing country that will invite many people into the country because of the investment and business opportunities that are present. The last thing we need to do is fight among ourselves about how certain ethnicity are supposedly “richer” than others. If we are truly a nationalistic country we will pull the reigns of our country together and not be dominated by foreign investment in the coming years. (kes)

***

Kenneth is a 17-year-old university student who loves comic books, Dota 2, movies, political science and history. You can reach him at @kenneth2098 on Twitter.

---------------

Interested to write for Youth channel at thejakartapost.com? We are looking for information and opinions from students with appropriate writing skills. The content must be original on the following topics: passion, leadership, school, lifestyle ( beauty, fashion, food ), entertainment, science & technology, health, social media, and sports. Send your piece to community@jakpost.com, subject: YOUTH. For more information click here.