The ever increasing number of drug addicts has prompted the government to take stringent measures, such as lifting the capital punishment moratorium. However, the government’s plan to treat 200,000 addicts this year might have been too ambitious given poor interdepartmental coordination and poorly equipped and understaffed rehabilitation centers.

by: Nani Afrida, The Jakarta Post

Master, not his real name, is not ashamed to admit his dark past as a drug addict of five years. Now 37, he began using putaw (low-grade heroin) as a high school student.

As a juvenile delinquent, he would share his substance with friends as well as his brother, who later died from an HIV-related disease. Feeling disgraced, his family sent him to a faith healer who treated him with herbs, massage and mantra.

However, the treatment left him no better off than before. Master would still frequently experience withdrawal symptoms, severe pain and extreme chills.

“I was cured thanks to two things. First, I had a strong desire to quit drug usage. Second, I managed to stay away from my addict friends. I moved as far away as I could and started a new life in a place where no one knew I was an abuser,” said Master, who works as a journalist.

Unlike Master, who had put his faith in traditional healing methods, Erry Wijoyo turned to modern rehab centers to heal his putaw addiction. Over the course of eight years, he had gone to three rehab centers, spending huge portions of his family’s hard-earned money along the way.

Just like Master, Erry believes a strong will to quit is the key to kicking the habit.

“Once you start using drugs, it is very difficult to stop even if you want to,” said Erry, who now works as program director at Yayasan Kapeta Indonesia, which provides rehab and training to addicts.

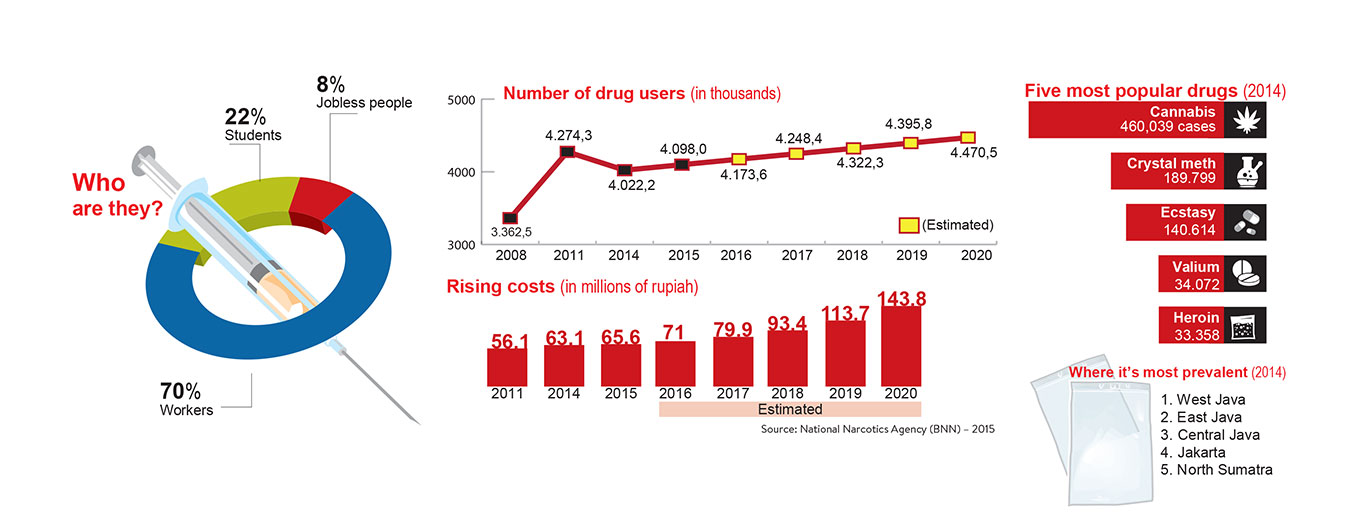

According to the National Narcotics Agency (BNN), Indonesia has about 4 million drug users. Unless the government makes significant improvements to its rehab facilities, the number is predicted to surge to 4.7 million users by 2020.

In June, President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo declared war on drugs. He stated that 50 people, mostly youth, die every day due to drugs. Official figures show that economic losses due to drug-related problems have reached Rp 63.1 trillion, accounting for money spent on drugs, treatments and rehabilitation fees.

Drug use remains a serious and unchanging problem, yet Indonesia has taken seemingly draconian measures, such as the death penalty. In the past, users were subject to imprisonment, but now they are sent to rehab.

Law No. 35/2009 on drugs requires that users be treated as victims entitled to medical and social rehabilitation.

However, state-sponsored rehabilitation programs have been far from reliable due to basic problems such as inadequate facilities and human resources. Annual targets seemed to have been set too high. In 2015, for instance, the government aimed to rehabilitate 100,000 drug addicts, yet BNN admitted it only managed to accommodate around 42,000.

BNN deputy chief of rehabilitation, Diah Setia Utami, has acknowledged that with poor facilities and rehab centers manned by fewer than 80 psychiatrists, the government is only able to manage 25,000 drug users annually.

“In view of those constraints, how could we possibly achieve the 100,000 target?” she said.

To solve the problem, the BNN has sought cooperation with other institutions, especially those with facilities that can be shared: the police, the military, the Social Affairs Ministry and the Health Ministry. More than 200 NGOs and Islamic boarding schools have also been taking part in the program.

Of the 578 registered rehab centers across Indonesia, only 18 are run by the government.

Ideally, stakeholders should have the same standards for rehabilitation programs. Sadly, each of them employs their own methods and techniques. Some of them adopt modern healing with counseling and therapy methods, while others practice traditional healing, which combines local wisdom or faith.

For instance, a rehab facility in Purbalingga, Central Java, has introduced the odd “boil therapy” practice, which puts the patient in a big pot containing an assortment of herbs. Patients are then warmed on a stove for 30 minutes. Management there have claimed their technique has healed “many” addicts.

BNN’s rehab center, Lido in West Java, mixes medical and social methods. First, the addicts are put in an isolation cell for medical treatment. Once over, they undergo therapy designed to prepare them to return to their communities.

It may sound all well and good, but Rudy did not find it fun when he spent five months in the Lido facility where, in addition to the routine medical treatments, he had to learn how to behave once he returned.

“After two months, I felt bored,” said the former member of the police’s Mobile Brigade (Brimob). “We were subject to verbal abuse, but it was nothing compared to situations I faced on the police force.”

The Lido rehab program, which lasts between three and six months, intends to prepare addicts to face life back in their communities, where they are then subject to stigma and discrimination. It also raises awareness about the menace of drugs. Besides traditional and government-run centers, drug users can also access modern centers ran by NGOs or foundations. Kapeta Foundation Indonesia, for instance, provides modern rehabilitation facilities.

The experience he obtained from previously managing four rehab centers in the past has inspired the foundation’s chief, Erry Wijoyo, to implement voluntary-based rehab strategies involving patients’ families. Kapeta does not lock addicts inside the rehabilitation center. Instead, they can go home, go to school and do whatever they please.

“We believe family involvement is very important in healing addicts. We have regular meetings with the patients’ families in which they can share their experiences as we find solutions together,” Erry said.

Founded in 2002, Kapeta implements different approaches for different addicts, believing that each individual requires different treatments. The facility does not set deadlines.The BNN is seeking to standardize rehabilitation programs in order to increase rates of success.

“We will talk with all stakeholders on what we should do and plan the kind of training that we need to carry out,” said Diah, a former director at the Drug Addiction Hospital in Jakarta.

Obviously, coming to an agreed stance with law enforcers is not easy. Even though the law requires that users be sent to rehab instead of to a penitentiary, law enforcers are still divided on the issue. This still happens despite the fact that the National Police, the Social Affairs Ministry, the Health Ministry, the BNN, the Supreme Court and the Attorney General’s Office signed a joint regulation on March 14, 2014, on joint rehab programs.

Statistics from the Law and Human Rights Ministry show that half of the 181,000 prisoners in Indonesia are convicts of drug-related crimes. Interestingly, 61,000 drug users have been imprisoned instead of being rehabilitated.

Complications usually occur when a suspect is both a user and dealer. Ministry officials say only “real” users are entitled to rehab.

“We implement the policy quite strictly,” said Akbar Hadi, the directorate general’s spokesperson for the ministry’s correctional institutions.

Drug convicts are classified into different categories: pure user, producer, dealer, courier or mix. Then the drug users are further classified again based on the way they abuse the drugs — whether by way of injection or orally. Subsequently, the user is required to undergo an HIV/AIDS test.

The numerous tests conclude whether or not the user is entitled to rehabilitation, and if services will be provided while serving time in prison. The intricate classification system is applied to make sure that drug dealers and makers do not end up in rehab centers.

In Jakarta, for instance, of the 17,000 prisoners, 11,000 are drug convicts and only 100 of them are rehabilitated behind bars.

Addiction counselor Eri Wibisono, who also provides counseling and training within prisons, has said that the rehabilitation program in penitentiaries is similar to that in Lido.

Apart from the ambitious rehabilitation program, the government does not seem to have any plans on what is going to be done to help former drug addicts who have returned to their families.

Dani, a former addict, rightly says, “I may have totally recovered from addiction, but looking for a job is quite challenging. Who is willing to employ a guy like me?”

A tale of new drugs and old-fashioned laws

A man has posted on kaskus.com his experiences after taking Tembakau Super Cap Gorilla (Gorilla brand “super tobacco”), a new type of drug that has become all the rave lately.

Posting under the name of “Dayu-dayu”, he warns that the effect of the new drug is so strong that it endangers not only the lives of those who consume it but also those of others.

“After the first puff, you’ll get a splitting headache in the right half of your head. If you’re lucky enough to survive, hallucinations will take you to a world of fantasy where you think you can do anything as you please,” he says.

“After the second puff, the dizziness disappears and the drug begins to affect your nerves and the hallucinations begin. My hands, feet and joints became numb […] I couldn’t focus. I tried hard to stay conscious, but I felt my body fall apart. There were various sensations at the same time: I felt the urge to puke, poop, pee and laugh.”

The National Narcotics Agency (BNN) says that the Gorilla tobacco contains a chemical substance called synthetic cannabinoid, a new drug first encountered in Indonesia last year. Users feel they are in a gorilla’s crushing embrace and it is assumed the drug was named after this sensation.

“The effect makes the user slow, lazy and drowsy and suppresses the appetite. After using [the tobacco] for some time, the user will become addicted,” BNN spokesperson Slamet Pribadi told The Jakarta Post.

Apart from the Gorilla brand tobacco, similar drugs come in several other brands like Hanoman, Nataraja and Badak — all are already on the BNN’s list of new dangerous drugs that should be banned.

But the dangerous drugs are widely available because until now they are still considered legal as they are not listed in Health Ministry Decree No. 13/2013 on drug classifications.

The tobaccos can be ordered from online shops for home delivery not only in Jakarta, but also in Sumatra, Sulawesi and Kalimantan. Consumers are mostly students and workers, according to the BNN.

In online shops, the Gorilla tobacco is offered for Rp 350,000 (US$26.43) a pack. Sellers exercise utmost caution and the order will be delivered by a courier only after the buyer has transferred the payment.

Nataradja and Hanoman, billed as “pure tobaccos”, are more expensive. For Rp 450,000, one can get a packet of 5 grams, while a 2.5 gram packet costs Rp 250,000. Interestingly, online shops keep updating their sales volume, with one shop citing that one product has recorded over 100 sales.

“We have called on the Health Ministry to put these drugs in the appendix of its Regulation No. 13/ 2013. It is difficult to tackle cases of the abuse of new drugs without proper regulations,” Slamet said.

Under the 2009 Health Law, dealers and users are subject to a maximum five years imprisonment for drug abuse. The law also stipulates that narcotic users undergo rehabilitation while dealers are sent to jail.

New drugs keep arriving from all over the world, with producers shrewdly changing tactics to outwit law enforcers. According to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNDOC), there were 216 new psychoactive substances (NPS) distributed worldwide in 2012. The number doubled to 430 in 2014 and to 643 in 2015.

How about in Indonesia?

Currently, 44 types of NPS exist in Indonesia, including the Gorilla super and Hanoman tobaccos and the number is expected to increase, BNN statistics show. Of the 44 new drugs, only 18 have been put on the list of the Health Ministry’s regulation on drug classification, while others are still on the waiting list.

To find solutions, the BNN has joined forces with the Health Ministry, the National Police, academics, chemists and health experts. Unfortunately, the effort has been hampered by sluggish bureaucracy and inadequate regulations.

New drugs are more dangerous because they are difficult to trace with conventional urine and hair tests. The BNN says many new drugs are made from synthetic chemicals, which require advanced skills and technology to detect.

A case in point was that of TV personality Raffi Ahmad, whom the BNN arrested in 2013 for drug possession. Officers were certain that he had consumed a new ecstasy-like drug from Singapore, but much to their surprise, he passed their urine tests.

Eri Wibisono, a drug addiction counselor at the BNN’s rehabilitation center in Lido, West Java, and at narcotics penitentiaries, says that once people get addicted, it is next to impossible to quit. Putting drugs on the long list for the purpose of legal processing is useless because more new drugs are flooding in anyway.

“This is not only about producers or dealers. Users can also create new drugs when they are in a drug withdrawal syndrome. It needs only basic knowledge about the substance to make a brand new drug,” Eri said.

He then recounted a story about his patient who became addicted to an over-the-counter drug and found one day it was no longer available in the drugstore. “This man examined all cough medicines on the market to find one that contained the chemical substances he needed. He bought 70 sachets of medicine to relieve himself from the syndrome,” Eri recalled.

Another reason why it is difficult to ban addictive chemicals is that many such materials are needed as basic components that doctors need for medication. “One thing we can do to stop new drugs is to completely ban all materials that can be used to make narcotics. But are we ready for a surgery without anesthetics?” Eri said.

| Editor-in-Chief | : | Endy M. Bayuni |

| Senior Managing Editor | : | Kornelius Purba |

| Managing Editor | : | Primastuti Handayani |

| Assistant Managing Editor | : | M. Taufiqurrahman |

| Desk Editor | : | Pandaya |

| Writer | : | Nani Afrida |

| Technology | : | Muhamad Zarkasih, Muhammad Kurnia, Mustopa |

| Multimedia | : | Bayu Widhiatmoko, I.G. Dharma J.S., Ahmad Zamzami, Rian Irawan |