Almost two years after the government launched an unprecedented and exceptionally successful crackdown on illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing practices, questions linger on how to economically capitalize on the success, particularly when the local fishing industry grapples with shortages of raw materials, forcing them to reduce operations and shed thousands of jobs. The Jakarta Post’s Rendi A. Witular explores the issues. This is the first of two series of reports.

by Rendi A. Witular

Dozens of locally made fishing vessels weighing more than 30 gross tons (GT) are docked idly at a port operated by fishing company PT Bintang Mandiri Bersaudara in North Sulawesi’s Bitung, the country’s biggest cluster of fish-processing plants.

One crew member said he had not gone fishing for more than a year now, but was still employed to keep the boat seaworthy. “A lot of my friends have been laid off. I am among the lucky few,” said the crew member.

Adjacent to the port is Bintang Mandiri’s cold storage and processing unit, which currently runs at less than 20 percent capacity, down from more than 60 percent before the government declared war on illegal fishing through a number of policies in November 2014.

Less than 5 kilometers from the site, PT Delta Pasific Indotuna, which exports all of its canned products to the Middle East, was forced to import tuna from India and South Korea in January after one buyer slapped hefty financial penalties and threatened to break its contract following the firm’s failure to deliver on time. Delta, with its products sold under the Aloha, Almandab and Manara brands, among others, is having trouble sourcing tuna after its suppliers, such as Bintang Mandiri, almost ceased operating in the wake of the implementation of the stricter IUU fishing policies.

Spearheaded by firebrand Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Minister Susi Pudjiastuti, the country’s war against illegal fishing has taken a toll on an unintended victim; the local fish-processing industry, which employs thousands of largely manual workers.

Mid-size fishing companies, such as Bintang Mandiri, which has never been involved in IUU fishing, employs Indonesian crews only, sources all its ships from domestic shipyards and receives capital for investment from state-run banks, have also fallen victim.

Around 10,000 workers have been dismissed in Bitung alone in the past year, according to North Sulawesi’s Association of Fish Processing Units (AUPI). The figure is far higher than the 1,700 workers claimed by the Maritime Affairs and Fishery Ministry.

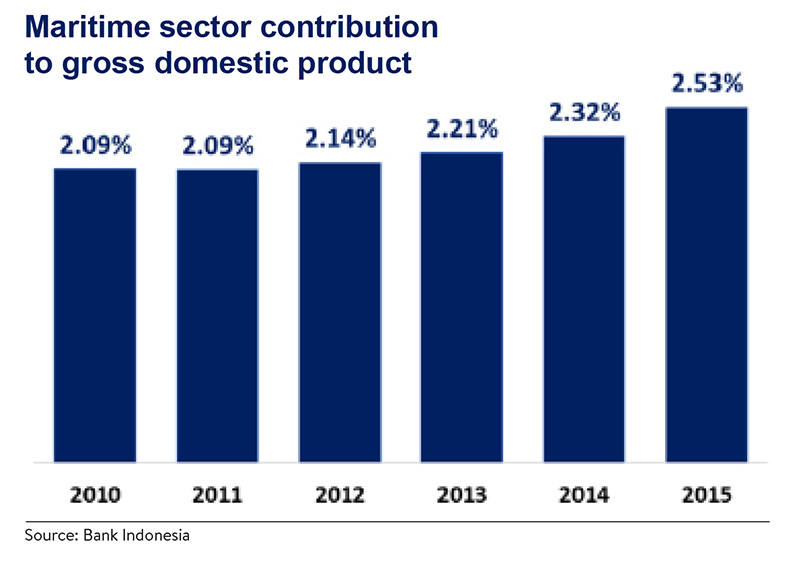

While local fishermen operating smaller than 10 GT boats are the immediate gainers from the IUU crackdown, as many indicators suggest, the past year has not been favorable to the fishing industry, particularly in North Sulawesi and Maluku — the provinces with the heaviest reliance on the fisheries business. Claims of difficulties by the industry may not be exaggerated or casuistic, as insisted by the ministry.

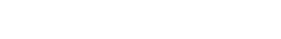

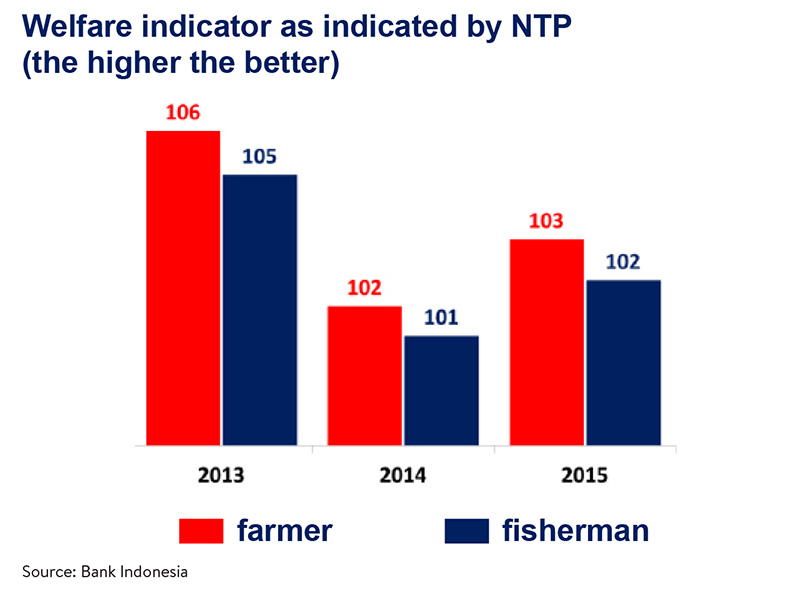

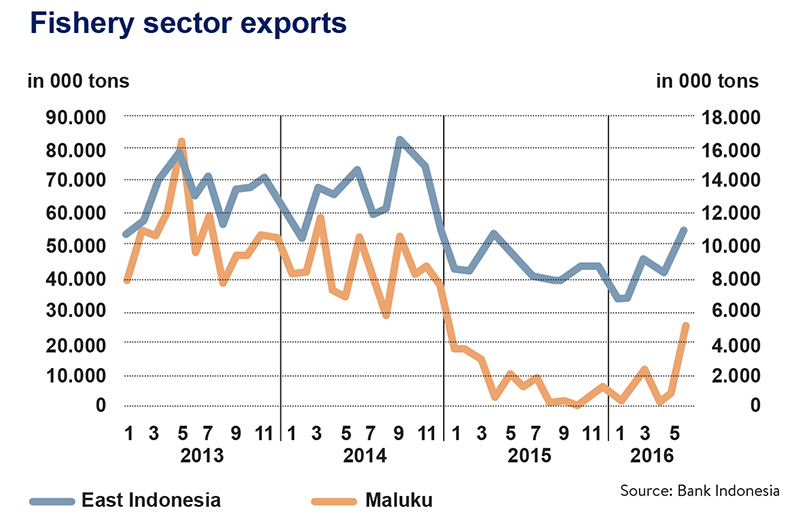

Bank Indonesia’s (BI) recent research on the regional economy, has blamed the rigid anti-IUU policy for the decline in economic growth in North Sulawesi and Maluku in 2015, where the fisheries sector is the economic backbone. Shortages in raw materials have severely hit the industry there.

The central bank said the economy in North Sulawesi slowed even further in the first and second quarter of this year compared to the same period last year, and the fisheries business has yet to fully recover despite several policy relaxations. Maluku also suffered a rise in unemployment early this year as layoffs in fisheries companies soared, according to the BI report, despite the province recording higher economic growth in the first and second quarter of the year with a recovery in fish catches.

Even the tuna-processing industry in Bali has also taken a hit with BI reporting that several export-oriented processing plants have ceased operations and shifted to catching squid.

BI’s findings, coupled with reports from industry representatives, seem to agree that the shortages in supply for the processing industry have been caused by the policy prohibiting transshipment — the practice by which a fishing boat transfers its catch in the middle of the sea to a transportation ship for delivery on land.

Transshipment has been blamed in the past for the widespread poaching that has caused the country more than US$20 billion in potential losses. Through transshipment, transportation vessels pool the catches, and directly ship them to Thailand, China, Taiwan and the Philippines without first being processed in Indonesia.

Nationalized foreign-made vessels, known locally as ex-asing and formerly operated as joint ventures with local companies, have been blamed largely for contributing to the illegal transshipment and for the widespread practice of illegal fishing. The ministry has banned the operations of more than 1,100 ex-asing ships since late 2014.

Adding to the problem, the total ban on transshipment covers all fishing companies, including those that have never been involved IUU fishing in the past and have employed locally made vessels only.

The policy, however, has triggered a domino effect in which fishermen with larger than 30 GT vessels, which usually sell their catches to industry, can no longer catch fish in an efficient way without transshipment. Supply to the industry has since been interrupted.

“If you want to get rid of the mice, don’t burn the barn,” said Rudy Walukow, the chairman of North Sulawesi’s Association of National Fishing Vessels (AKPN), which groups together owners of Indonesia-made fishing vessels only.

“We fully support the ban against transshipment for delivery to other countries. That should not be lifted in any way. But please, we need to have the regulation relaxed for transshipment to local ports,” Rudy said.

Transshipment is required particularly for big fishing boats sailing more than 10 miles off coast so that they do not have to return to their port of origin once they are fully loaded, as they can transfer the catches into transportation vessels.Following widespread protests demanding the reinstatement of transshipment for local delivery, the Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Ministry issued a regulation in late April to allow the practice, but under strict supervision and mechanisms.However, the required mechanisms reportedly cannot be fully applied on the ground.

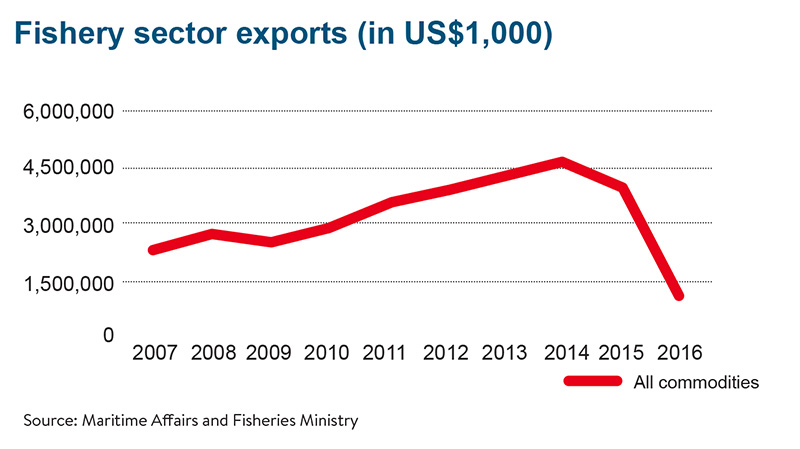

Probably out of concern for the poor performance of the fisheries industry, as its exports suffered a 15 percent plunge last year, President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo issued in late August a presidential instruction for all relevant ministries to take measures to accelerate fisheries development.

The instruction requires, among other issues, that the Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Ministry evaluate regulations hampering the sector’s development and increase fish catches and cultivation to boost raw material supply for the industry.

The instruction also came amid reports that while the domestic processing industry has been undermined, similar businesses in General Santos in southern Philippines, located near Bitung, peaked in the first half of this year after plunging last year as it reeled from the impact of the IUU crackdown in Indonesia.

Supplies of raw materials to General Santos have long been suspected of being illegally sourced from Indonesian waters.

“I don’t think they get the fish directly from Indonesian fishing vessels because of the strict supervision,” said AUPI chairman Basmi Said. “I have received reports that because we don’t catch the spawning migrating fish, the Philippine fishermen take advantage of them with their fishing vessels waiting on the border to net them.”

Despite the pervasive concerns, Susi has signaled she will not authorize further relaxations. The iron lady has argued that because IUU fishing in Bitung and nearby areas remains rampant, it would be a mistake to provide more leeway.She claimed many Philippine transportation vessels had approached the waters near Bitung to conduct transshipment with local fishing vessels, and she has demanded that the Navy’s Eastern Fleet take the problem seriously by increasing its patrols there.

“That explains why General Santos is thriving again. I was initially reluctant to allow the transshipment there, but many people demanded it. Now we have seen the consequences,” she said.

Transshipment: A double-edged sword

Transshipment is a practice in which a fishing boat transfers its catches in the middle of the sea to a transport vessel for delivery to other places, ideally to local ports or fish processing units (UPIs).

It has been blamed in the past for widespread poaching because through transshipment, transport vessels pool the catches and ship them directly to Thailand, China, Taiwan and the Philippines without first being processed in Indonesia.

But the system is required particularly for mid-sized to large fishing boats sailing more than 16 kilometers offshore so that they do not have to return to their ports of origin once their holds are fully loaded as they can transfer the catches to the transport vessels.

The total ban on transshipment in November 2014 hit all fishing companies, including those that have never committed illegal fishing.

The policy, however, has triggered a domino effect in which fishermen with more than 30 gross ton (GT) vessels, whose catches are usually for industrial use, can no longer catch fish in an efficient way. Supply to the industry has since been interrupted.

Catching fresh tuna for delivery to Japan, for example, will require transshipment. It takes a fishing boat from the Muara Baru Port in North Jakarta 14 days to arrive at its fishing concession, while fresh tuna should be on a consumer’s plate no more than 16 days after getting caught, by Japanese standards, said Tachmid Widiasto, the chairman of the Muara Baru Fishing Companies Union (P3MB).

“It’s just impossible for the fishing vessel to meet the standard if they have to catch the tuna and then return to Jakarta. That would have already taken 28 days. The role of transshipment with a transport vessel is to facilitate the delivery,” said Tachmid, whose association members only include the operators of 1,600 domestically made fishing boats.

In response to protests from businesses, the Maritime Affairs and Fishery Ministry issued in late April a directorate general regulation to allow transshipment.

However, the relaxation comes with a string of requirements that include installing CCTV cameras and fishing monitoring systems (VMS) on the transport boats. A ministry staff member is also required to be on board the ship while sailing to ensure the vessel is not transferring the catches to overseas buyers. Fisheries businessman Rudy Walukow recently pointed to his three transport vessels that had complied with the newly issued transshipment regulation. “I’ve spent more than Rp 100 million [US$7,700] to install two CCTV cameras on each boat and a new VMS as demanded by the regulation,” said the chairman of North Sulawesi’s Association of National Fishing Vessels (AKPN).

“Although it is expensive and complicated, what other options do I have?” said Rudy, whose company PT Bintang Mandiri Bersaudara has more than 70 locally made ships of various types.

Rudy is possibly among a few businessman in Bitung, North Sulawesi, who can thus far afford to comply with the regulation. There are about 100 locally made transport ships in Bitung, but most of them are reluctant to comply, given the complicated mechanisms in the new transshipment regulation.

“The regulation to relax the ban on transshipment is just too complicated. We can meet the supervision requirements, but for the transport ship to be able to serve only three fishing boats is just not efficient,” said Tachmid.

Aside from the inflexible mechanism that has discouraged others from complying, Tachmid and Rudy pointed to suspected foul play in the procurement of the CCTV cameras required by the regulation.

They accused the ministry of “directing” them to buy a certain type of CCTV camera sold only by one supplier. The ministry’s acting director general of fishing, Zulficar Mochtar, said he would follow up on the allegation.

“There should not be any monopoly for the CCTV. I will check and ensure this will not happen,” he said.

— JP/Rendi A. Witular

Shortage in fish supply for industry not national-level problem

A shortage of raw materials has struck the local fish-processing industry as it reels from the impact of an expansive crackdown on illegal fishing. The Jakarta Post’s Rendi A. Witular recently talked to the Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Ministry’s acting director general of fishing, Zulficar Mochtar, on the ministry’s response to the problem. The following are excerpts from the interview:

Question: The processing industry, particularly in Bitung, North Sulawesi, and Muara Baru in Jakarta, has lodged complaints over raw material shortages. How do you respond to this?

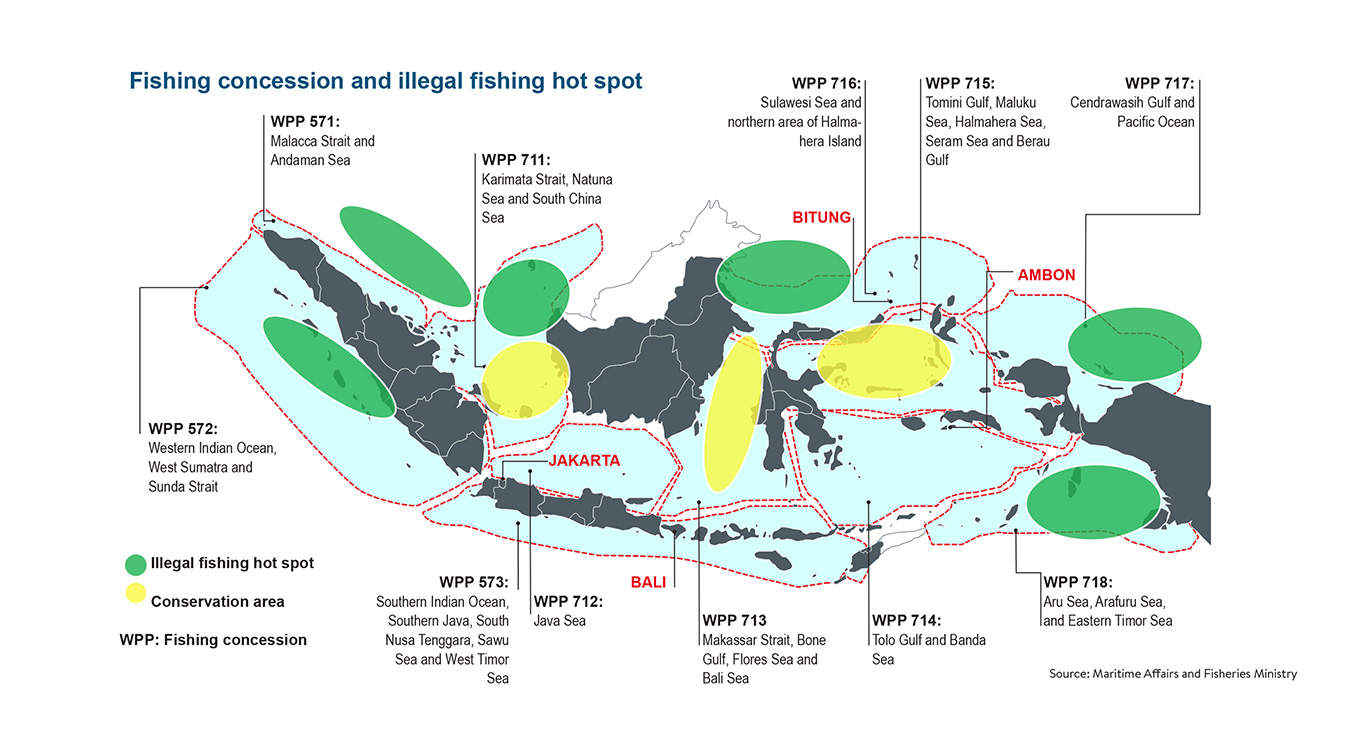

Answer: The ministry has conducted an analysis and evaluation of 1,132 nationalized foreign vessels [known locally as ex-asing and formerly operated as joint ventures with local companies]. Because all have violated the regulations, minor and major ones, the ministry has terminated their operations. Many of these vessels used to operate in Bitung, Ambon and Tual in Maluku and Merauke in Papua. These locations are notorious for illegal, unreported and unregulated [IUU] fishing activities. In the past, many fish processing units [UPIs] received their raw materials from these vessels.

With the vessels no longer operational, the supply of raw materials to the UPIs has been cut. At the same time, we have seen a more than twofold jump in the volume of fish caught by small fishermen in Bitung after the illegal fishing crackdown. The problem in raw material shortages is because there has been a disconnection between supply from the fishermen to the industry.

The industry operates without any limitation by seasons, and they have quality and quantity standards that should be continuously met while traditional fishermen usually set sail for as much as nine months in a year and their catches are of various sizes.

Our job now is to upgrade the fishermen’s capacity to cope with the industry demand, and the UPIs should sit together with the fishermen to work out an amicable partnership. We will push for such partnerships although they will take time to implement. Another alternative for the industry in sourcing the supply is through imports. This year so far, imports have declined by 50 percent compared to the same period last year.

Another problem in the industry is its installed capacity. In Bitung, for example, they have 54 UPIs and their overall capacity is just too big, although in practice they used to run at only 50 percent capacity.

Because it is impossible to fulfill 100 percent, there should be a verification of the industry’s claims. We should not comply with their demand unless we really know the exact amount of their confirmed orders.

The UPIs have long depended on the ex-asing vessels, and now they have to adjust the way they source their material by partnering with small fishermen. The problem in Bitung is an isolated case, and it does not occur in most other areas.

Because Bitung is an IUU hot spot, it deserves special treatment. I have recently found out that a lot of the fish from the area have been illegally shipped to General Santos [nearby fish processing cluster in the southern Philippines]. Although we have put in place strict supervision, such practices still occur. Many fishing vessels under 30 gross tons (GT) transfer their catches to transportation vessels in the middle of the sea for delivery to General Santos. That explains why the fisheries industry there is peaking again after a plunge last year following our policies against IUU fishing.

In the case of Muara Baru, much of the fish there has been supplied from Bitung. The crackdown on IUU practices in Bitung has caused supply interruption. Again, we have to verify the confirm orders there because we are suspicious that the problems only occur in specific places but are blown up as though it is a national-level problem.

Question: Local fishing companies and UPIs have proposed the relaxation of a regulation on transshipment so that they can efficiently catch more fish to address the raw material shortages. How do you respond to that?

Answer: What we prevent is the transshipment for delivery to other countries. We have already relaxed the regulation by allowing transportation vessels to deliver the catches to local ports only and for UPIs. If we find the regulation to be too inflexible, we will try to include it in the upcoming revision of Ministerial Decree No. 30 on the fishing business. But it will not mean that we will allow even a slight crack in the transshipment policy that can be misused for our fish to be illegally transported overseas.

Question: So what will be included in the upcoming regulation revision?

Answer: Transshipment [for overseas delivery], the use of foreign vessels, the negative investment list for the fishing business are off limits from the revision. Input from the public includes the need to relax transshipment [for delivery to local ports]. In Bitung, we have allowed 10 transportation vessels to operate, and we will see whether this has been well accepted by businesses. Other issues in the revision will include harmonization and simplification of the many different regulations on the fishing business, including requirements for fishing vessels. We hope to pass the revision in October at the latest.

Question: Some of the 1,132 nationalized vessels have received ‘clear status’ from the audit. Can they operate now?

Answer: No. They have to deregister, meaning that after paying all the taxes they are required to leave the country because they are of foreign origin, and we have prohibited the use of any foreign-made fishing vessels. The minister’s policy has saved the majority of our fishermen who own vessels of below 10 GT. Such vessels account for around 90 percent of all fishing vessels in Indonesia. Our local shipyards are now flourishing as they have received many orders to replenish the gap left by the prohibition of foreign-made vessels. There has also been a jump in the demand for new fishing vessel licenses in the past year.

Question: But some of the cleared vessels were bought in early 1980s or bought through an open and fair bidding process upheld by our courts. Should this kind of vessel be barred from permanent use here?

Answer: Foreign-made vessels are off limit. We’ve been very traumatized by these kinds of vessels. But the example that you mention is very casuistic. But in principal they also have to deregister.

Question: What happens if they don’t want to deregister?

Answer: We will turn their vessels into rumpon [artificial reefs].