It has been 10 years since the National Police established Women and Children Protection (PPA) units across the country to handle the rising cases of violence against this most vulnerable group. However, the units have yet to perform as the public expected.

When the PPA was set up in 2007, people hoped it would play a leading role in the effort to curb the uptrend in violence against women and children. It was born out of concern about crimes such as rape, domestic violence and human trafficking.

Its professionalism and dedication were expected to reverse the worrying situation. From then on, victims have had a formal institution from which to seek help and on which to pin their hopes for stringent law enforcement.

Today, the unit is available at the National Police headquarters in Jakarta and in its approximately 500 district commands (Polres) across the archipelago. Each regional police station spares a room embellished with toys and other child-friendly paraphernalia.

Thanks to its relatively wide reach, it is gaining recognition. A major case that helped lift its profile is its role in the revelation of last year’s gang rape and murder of a 14-year-old junior high school girl, Yuyun, in Bengkulu.

Especially impressed by the PPA’s performance is the Indonesian Police Commission (Kompolnas), although it still wants to see it continue capacity-building by providing officers with more training on human rights and gender issues.

“Upgrading PPA officers’ skills and knowledge is important, especially for those posted in remote areas,” commissioner Poengki Indarti said.

So far, aside from joining forces with the Law and Human Rights Ministry for training on legal matters, the PPA has also linked up with global organizations like United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

However, people who have had a personal experience of taking their plight to police may regard the commission’s picture about the PPA as too rosy. In spite of its reach, the women and children protection unit has won little public confidence because of, basically, a lack of competence and empathy toward victims who undertake the pain of reporting their cases.

The Post’s recent interviews with three sexual assault victims, F, R and T, provide a glimpse of how police have let people down and how much they would have to do to win public trust. F, now 26, said she was raped by a friend, but her family had wanted to keep the secret to themselves because they were afraid reporting it to police would only make the “disgrace” even more burdensome. Unable to bear the psychological load, she reported the incident to police — only to regret she did it after officers on duty threatened to send her to prison if she failed to prove her case.

She dropped her report and has since tried hard to overcome the trauma from the rape and from the police’s harsh treatment. “I just couldn’t make sense of the police’s insistence that rape can be consensual.”

Red tape remains notorious with the police where time and financial efficiency should be of the utmost importance. When R reported a man who allegedly assaulted her 3-year-old son in December, the case has virtually been buried in time.

He felt he was left in the cold when officers on duty browbeat him. They told him they would need a clinical examination of his son that would cost him Rp 1.5 million (US$112.52) as the prerequisite legal evidence before they could go get the suspect. Too costly for him, he balked at the request.

R did not hear from the authorities for three months after he filed his complaint with the Palmerah Police in West Jakarta. Thanks to intervention from the Child Protection Commission (Komnas PA), police eventually rang him in early April, telling him that his son could have a free examination at the Kramatjati Police Hospital in East Jakarta. He complied, but until today, he has heard nothing more from police.

“I’m afraid the perpetrator roams free and looks for his next prey,” he said. While R has been left in uncertainty for five months, T eventually saw the sexual abuser of her 5-year-old daughter detained after two years. She would regularly go and check how far investigators had progressed in her daughter’s case. Along the way, police claimed to have lost all evidence twice and had to resume the investigation all over again. This brutally reopened the child’s traumatic moments of being raped by her uncle.

When the case was eventually settled in court last year, T learned the handling of her daughter’s case was drawn out because the initial chief investigator had received a bribe from her relatives, who had wanted the case to be shelved for fear that prosecution would bring shame to the extended family. In some cases, the widely shared stories about officers’ lack of professionalism, competence and integrity has led victims to rescind their police reports. They are the bogeymen for victims of violence seeking legal avenues to resolve their cases.

Earlier this year, Adj. Comr. Bambang Edi, an East Jakarta general crime unit head, reaped a backlash for his insistence that groping a woman’s thigh in public as a commuter had done on a bus a few days before did not constitute a crime. He said the “educated looking” man, who was reported to police, did it only “for a joke.”

As the groping controversy barely receded, Jakarta Police spokesman Sr. Comr. Raden Prabowo Argo Yuwono shot himself in the foot while he was commenting on the incident: “Let’s see what actually happened. Which of her thighs was touched? The left or right one?”

Despite high public expectations, PPA has yet to obtain adequate financial and human resources. Even the Jakarta Police’s PPA unit still frets about the problem. Of its nine investigators, only two are women.

The Women’s Legal Aid Institute (LBH Apik) notes that during questioning, investigators often ask aggressive and offensive questions like, “Why did you go with the suspect in the middle of the night?” In some cases, victims were asked to collect evidence or confront their alleged attackers.

“Rape usually occurs in a closed space. How can the victim possibly find a witness?” LBH Apik activist Tuani Sondang Rejeki Marpaung asked. The sense of insensitivity and lack of empathy toward victims demonstrated by investigators has also been reported by the National Commission on Violence Against Women (Komnas Perempuan).

“A rape victim recalled a cop asking her: ‘Did you enjoy the sex?’” said commissioner Choirunissa.

Besides, it is common that police force an out-of-court settlement and help arrange marriages between victims and rapists. Unable to stand the pressure, many victims withdraw their reports.

Komnas PA coordinator Arist Merdeka Sirait pointed out that the lack of competence, sensitivity and empathy, combined with the slow-moving bureaucracy, have exacerbated victims’ trauma and discourage them from seeking legal solutions to their cases.

“Many victims just cannot endure their embarrassing plights being exposed.” Last year, the commission received 2,426 reports of violence against children, 58 percent of which were cases of sexual violence. It believes the actual number of cases is much higher, especially in isolated areas where access to the PPA is limited. Instead of going to the PPA, villagers may refer their cases to the subdistrict police offices (Polsek), where the dispute is settled out of court, allowing perpetrators to enjoy impunity.

Of profound concern is that 40 percent of the cases reported to police were dropped because the victims could not afford to undergo the costly clinical examinations that police demand to support their claims.

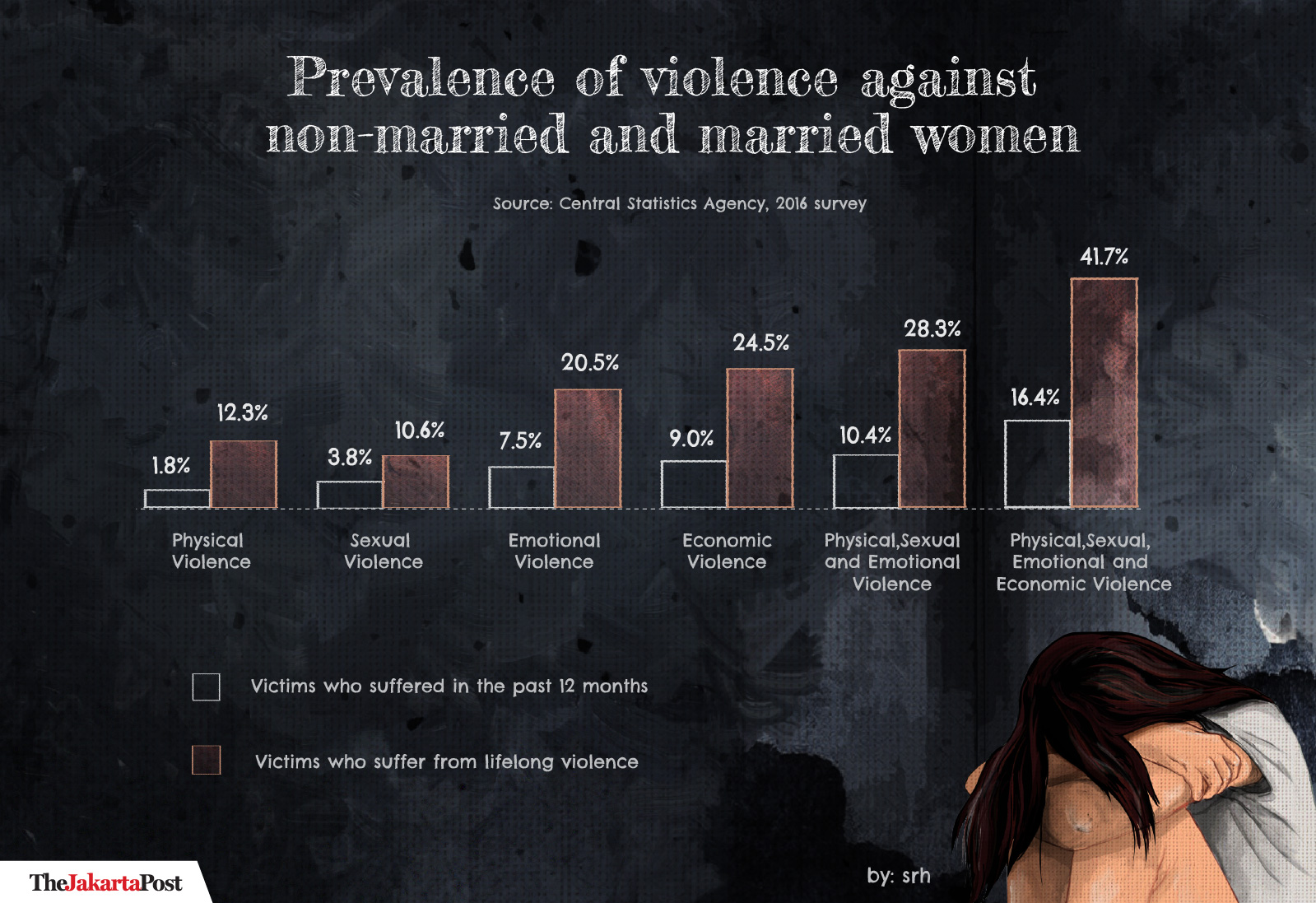

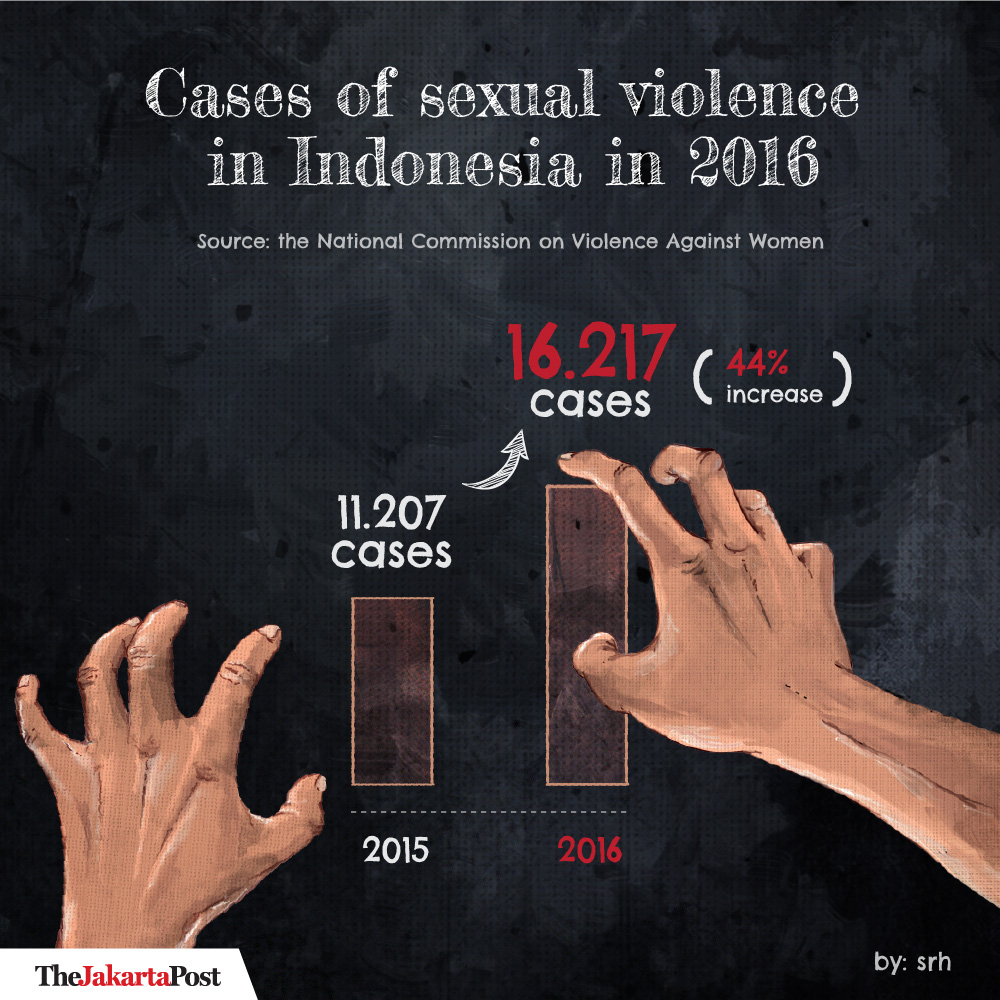

Also last year, Komnas Perempuan recorded almost 260,000 cases of violence against women, down from 322,000 cases in 2015. They were mostly domestic violence.

Despite high public expectations, PPA has yet to obtain adequate financial and human resources. Even the Jakarta Police’s PPA unit still frets about the problem. Of its nine investigators, only two are women.

Although funding is better this year, it remains short. “Sometimes, our officers have to fork out cash from their pockets to pay victims’ clinical examination bills,” its chief, Comr. Endang Sri Lestari, says in her office. The yard is equipped with swings and slides to look children-friendly.

In fact, victims can have their clinical checks at the Kramat Jati Hospital free of charge, but given the overly long waiting lists, many have to turn to other hospitals. A single check costs about Rp 1.6 million, which is too much for some victims. Early this month, acting governor Djarot Syaiful Hidayat promised to exempt violence victims from charges.

As for professional training, Endang says PPA officers have the opportunity to attend courses “several times” a year. Every one of them is certified as a specialized investigator, too.

PPA offices elsewhere have yet to benefit from the recruitment of 7,000 policewomen in 2014. Currently, fewer than 50,000 of Indonesia’s 430,000 police officers are female.

It turns out that the police’s organizational structure puts PPA in a less “promising” position, where good jobs do not automatically merit promotions. Bambang Rukminto from the Institute for Security and Strategic Studies (ISSES) says Police Academy graduates would do everything to get deployment in other more strategic units for faster promotions. Clearly, PPA does not interest the police force’s best and brightest.

As police observer Bambang Widodo Umar and commissioner Poengki emphasize, PPA’s job is more than law enforcement. Equally important is protection of victims and prevention of crimes against women and children.

— Rachmadea Aisyah , contributed reporting.

Dating violence: Who’s got the power?

When Shinta, not her real name, and her boyfriend fell in love with each other five years ago, their relationship was all innocuous, but as time went by he became abusive and she now hates herself because she realizes she is unable to break it off, let alone report the mistreatment to the police.

Until today, the 20-year-old woman has suffered verbal and physical abuse. “When losing his cool, he sometimes punches or slaps me, or kicks me hard like a ball,” she said.

“Once he beat me up and I almost fainted. He did say sorry, but he has done it time and again.” She is forgiving because she believes her boyfriend will mature and his behavior will change.

Disheartening dating violence has also been experienced by Shafira Amalia Hidayat, 20, in Bandung, West Java. Her story is about the lingering emotional troubles she has suffered since she severed her relationship with her boyfriend a year ago.

Shafira broke off their relationship after he regarded her as a “problematic” woman. His behavior changed after she confided to him of a past that she would not reveal to anybody else. She blames herself for the short-lived romance and this guilty feeling has been haunting her. “He never abused me physically, but he would keep telling me that my past troubled him.”

Abuses in dating relationships like Shinta and Shafire experienced have been alarming for many years. The statistics are troubling. The National Commission on Violence against Women (Komnas Perempuan) recorded 2,170 cases of dating violence last year. The number accounted for 21 percent of the 10,200 reports of violence against women the commission received. Although it was a 3 percent slide from 2015, the figure is still high.

Although cases of sexual abuse have risen, Indonesia has yet to have laws specifically addressing sexual violence in general. The law on domestic violence addresses only abuses involving family members, including a family maid, while cases involving other parties are dealt with the Criminal Code (KUHP).

Trying to break the impasse, Komnas Perempuan has championed the drafting of a bill on sexual violence. The good news is that the House of Representatives likes it. Lawmaker Ledia Hanifah from the Prosperous Justice Party (PKS) says deliberations may start soon and the bill may be endorsed by the end of the year.

Contentious issues include molestation, sexual exploitation, use of contraceptives, abortion, rape, betrayal of marriage vows, prostitution and slavery. Prison terms are set at between five and 20 years.

Investigators ask child rape victims ‘terrible’ questions

For child rights activist Arist Merdeka Sirait, there is nothing that enrages him more than police investigators asking a teenage sexual assault victims questions like, “How did you feel when they were raping you?” or “How did they do it?”

As a member of the independent National Commission on Child Protection (Komnas PA), Arist often accompanies teenage victims of violence while they are being questioned by the mostly male officers manning the Women and Children Protection (PPA) desk in local police offices. He knows that such aggressive questions psychologically hurt the victims even more.

“These questions make me angry. How could they ask a little girl how she was feeling being raped? What a terrible question! They should dig for more information to prosecute the perpetrators instead of exacerbating her trauma,” Arist told The Jakarta Post.

“These children were already traumatized by the incident and even more so when they told their stories to their parents. Then the police worsen their ordeal by asking those crazy questions. They are children who should receive appropriate treatments.”

The latest high-profile case that the commission co-handled was last year’s gang rape of two junior high school students in Pematang Siantar, North Sumatra. It sparked a nationwide outcry after the girls died while their case was under investigation and the alleged perpetrators were still on the loose. The commission alleged that the prolonged rigorous police questioning had made their depression worse.

Komnas PA points out that PPA officers’ most common mistake is that they treat child victims the way they treat adults. Teenage suspects are detained in the same cell as adult ones. This indiscriminate approach conflicts with the 2002 law on child protection and international conventions that Indonesia has ratified.

Bambang Rukminto from the Institute for Security and Strategic Studies (ISSES) underlines the need for PPA officers to have a good grasp of women and children issues. “There should be awareness among them of the importance of PPA and this needs a change in their mindsets.”

A lesson police, especially officers in charge of PPA, must learn from is the apparent mishandling of a case that resulted in a guilty verdict in 2013 for Yusman Telaumbanua for murdering three people in 2012. The Gunung Sitoli district court in North Sumatra subsequently sentenced Yusman to death.

The questionable sentence came to light after the Commission for Missing Persons and Victims of Violence (Kontras) discovered that Yusman was only 16 years old when he committed the crime. Both national and international justice systems rule that the maximum penalty for a minor is 10 years’ imprisonment, not death.

| Producer | : | Ika Krismantari |

| Writers | : | Agnes Anya, Nani Afrida, Nurul Fitri Ramadani |

| Senior Managing Editor | : | Kornelius Purba |

| Managing Editors | : | Primastuti Handayani, M. Taufiqurrahman |

| Desk Editors | : | Pandaya, Imanuddin Razak |

| Art & Graphic Design Head | : | Budhi Button |

| Technology | : | Ega Anugrah, Muhamad Zarkasih, Mustopa, Sandy Riady Hasan, Sarah Naulibasa |

| Multimedia | : | Bayu Widhiatmoko, I Gede Dharma JS, Ahmad Zamzami, Rian Irawan |