Hope and despair fills the first half of 2017 in efforts to protect the rights of women and girls. In late April the first ever Indonesian Women Ulema Congress issued a fatwa on preventing child marriage and ending sexual violence. Yet, child marriage remains legal, and deliberation on a sexual violence bill has stalled.

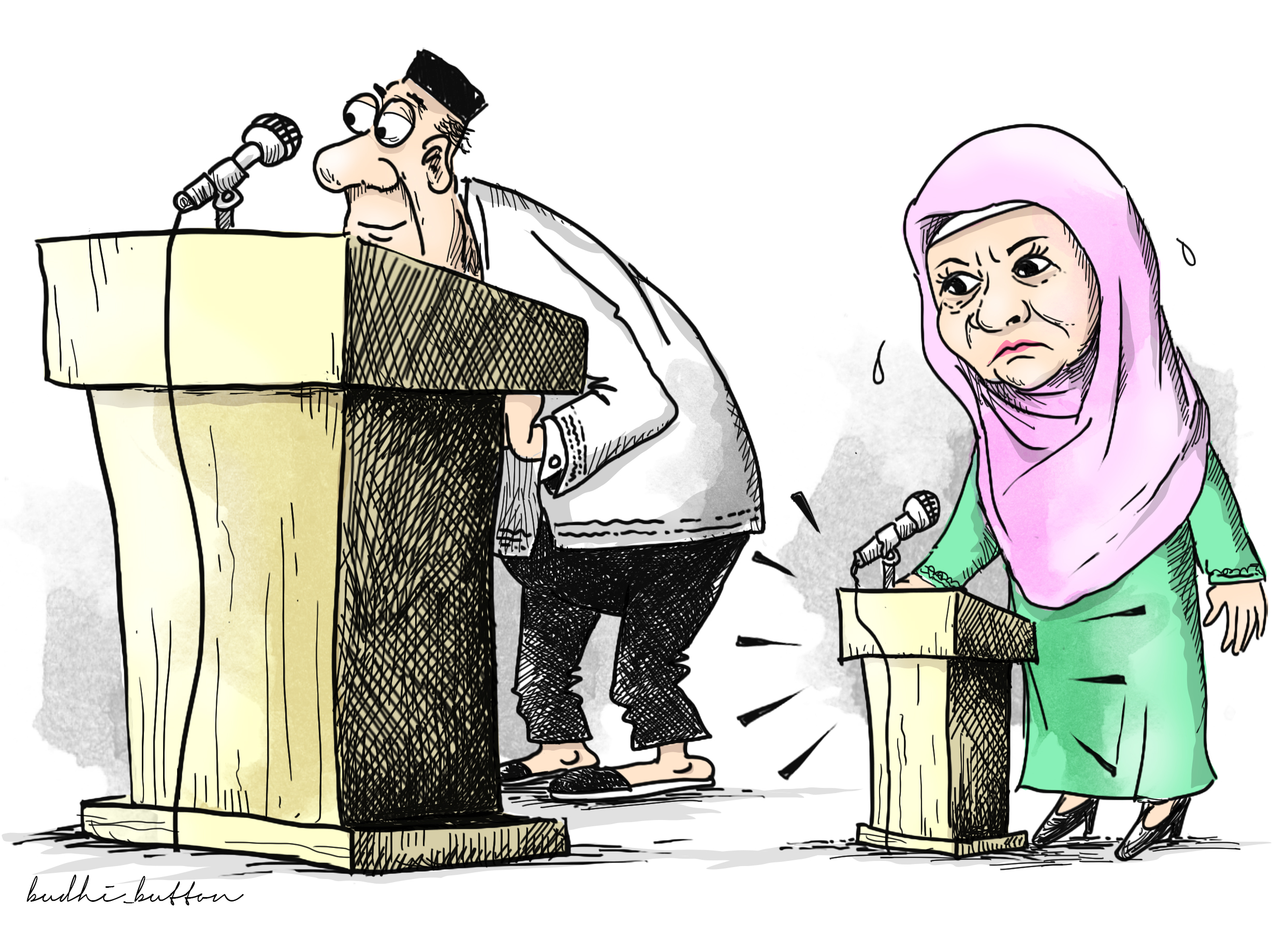

In the highlands of North Sumatra province, preacher Nani Ayum Panggabean was invited to speak at a celebration of Isra’ Mi’raj (Ascension Day of Prophet Muhammad). Her sermon dwelled on a popular theme: how to build harmonious relationships within the family.

The leading preacher quoted relevant Quran verses, such as one stating “that men and women are equal; that men must treat their wives well and be the family breadwinners.” When delivered in cities like Medan, the provincial capital, the message should stir “no problem.”

“But the next day the village chief’s wife came to me, saying, ‘Please don’t say such things [...], we’re ashamed; we’re quite fine. Just preach on Isra’ Mi’raj.”

So Nani questions how messages of the first ever recent women ulema congress could, with the support of local authorities, reach villages to help change such views.

Around the beautiful Lake Toba, the preacher said, men do not exactly abuse their wives. “But there women usually work on the farms while men sit around at coffee shops,” she said. Her remarks were met by grins from the men.

Nani was among some 1,200 participants at the congress and a preceding international seminar focusing on “the role of women ulema in strengthening values of Islam, nationhood and humanity.”

The collective voice of local and foreign women clerics and pesantren (Islamic boarding school) leaders shattered chronic neglect of urgent issues at the grassroots level, including the victimization of women and girls.

Yes we can: Students walk to the Kebon Jambu Al-Islamy Islamic boarding school in Cirebon, West Java. The school hosted a three-day national congress in April, where hundreds of female clerics from across the country discussed challenges Indonesian women face. (JP/Nurul Fitri Ramadhani)

Yes we can: Students walk to the Kebon Jambu Al-Islamy Islamic boarding school in Cirebon, West Java. The school hosted a three-day national congress in April, where hundreds of female clerics from across the country discussed challenges Indonesian women face. (JP/Nurul Fitri Ramadhani)

From the main venue at Kebon Jambu Al Islamy pesantren in the village of Babakan Ciwaringin, Cirebon, the women ulema issued three historic fatwa to loud applause.

The first stated that “preventing child marriage is mandatory,” and therefore it is the responsibility of the government, parents, teachers, religious figures and informal leaders to prevent child marriages.

In response, Religious Affairs Minister Lukman Hakim Saifuddin said when closing the congress that he would take up the fatwa with other government offices. This would mean a commitment to overcome the fact that the legal age for marriage is 21, but with parental consent girls can marry at 16 and boys at 19 or younger -- in line with the 1974 marriage law upheld by the Constitutional Court, A famous cleric, for example, wed his son at 17 last year, despite criticism.

The second fatwa, which states “all forms of sexual violence is haram,” both within and outside marriage, goes against long-standing views that a woman faces hell if she refuses her husband’s sexual advances.

The third fatwa ruled that “development which exploits the environment is haram,” as discussions at the congress had revealed increasingly difficult access to resources amid reckless development across villages.

Photo op: Participants pose during the first In¬done¬sian Women’s Ulema Congress in Cirebon, West Java. (JP/Nurul Fitri Ramadhani)

Photo op: Participants pose during the first In¬done¬sian Women’s Ulema Congress in Cirebon, West Java. (JP/Nurul Fitri Ramadhani)

Daily experiences of these female religious leaders and conditions of women and communities eventually led to the urgency of strengthening the role of female ulema. But many women religious figures are also beholden to patriarchal views, “especially if they benefit from the system,” said lecturer Nur Rofiyah. As a result, the congress led to the concept of “women’s ulema,” meaning female and also male “pro-women” ulema “who possess and incorporate gender perspective in their actions.”

In practical terms, the congress raised the need for more special training of female ulema, especially through sharia faculties in Islamic higher education. But regardless of formal education the women encouraged each other that “it’s never too late to learn,” said Nyai Masriyah Amva, the host of the Cirebon congress.

While such leaders cited family and community members who held them back, they also credited mothers, fathers or fathers-in-law who encouraged them to learn; while other relatives would resent a clever woman in their midst “who was allowed freedom to sit and study,” Nyai Ruqoyyah, a pesantren leader from Bondowoso in East Java, was cited as saying.

With personal experiences including forced child marriage, abuse and widowhood, the women leaders eventually drive independence and courage in other women and youth in their pesantren and communities.

“Nyai (Masriyah) told us that we will have to study to become independent,” said a graduate of the Al Islamy school, Hilyatul Aulia. In her village in East Cirebon she was the only unmarried 18-year-old. The belief is that girls would be old maids if they are not engaged by 15, said Hilyatul, now a student at a nearby institute.

Another graduate, promising young female ulema Neng Yanti Khozana, echoed the challenge of a small recruitment pool for female religious leaders. Once a girl is considered mature enough, she said, they are taken out of school to be married off, often preferably to relatives, such as in Cirebon.

Pesantren owners seek males to lead their schools, so kyai who have no sons wed off daughters as the son-in-law will inherit the pesantren leadership. For poor families, it is a matter of status and pride when someone asks for the hand of their daughter, especially if she has studied at a pesantren.

Like other women, the first challenge of a Nyai is their own marriage; despite their mastery of religion they can “get drowned” in a life dominated by the kyai. After each trip Indonesians expect oleh-oleh (gifts); and one preacher said hers was very special.

“The oleh-oleh that I take from here is [a lesson from] Nyai Masriyah that one only needs to lean on Allah,” said a participant from Surakarta, Central Java. With this she said she was sure she could spread heretical sounding things from the congress, such as the idea that a woman is not automatically and totally subordinate to a man.

“This understanding is still taught across pesantren in Surakarta,” she said, declining to give her name. She added a lengthy “process” was required to teach new notions, such as that negotiation is possible and necessary between husband and wife.

Center of attention: Religious Affairs Minister Lukman Hakim Saifuddin makes a speech on the role of female clerics at the first In¬done¬sian Women’s Ulema Congress in Cirebon, West Java, on April 27. (JP/Nurul Fitri Ramadhani)

Center of attention: Religious Affairs Minister Lukman Hakim Saifuddin makes a speech on the role of female clerics at the first In¬done¬sian Women’s Ulema Congress in Cirebon, West Java, on April 27. (JP/Nurul Fitri Ramadhani)

‘Adam’s most crooked rib’: Trauma emboldens female clerics

At the recent first-ever congress of female clerics in Cirebon, West Java, participants expressed different opinions on gender relations between husbands and wives.

While several interviewees said women and men were equal, some said wives should be totally submissive to their spouses to earn a place in heaven; as wives were akin to “Adam’s most crooked rib”.

However, survivors of child marriage and domestic abuse do not spread such messages – especially when they become religious leaders.

Ruqoyyah of Bondowoso, East Java, recited her experience of forced marriage at the age of 14.

After being divorced, she wed a man who would often hit her.

“I was told to be patient,” she said. He eventually became a lawmaker, and once, after she had confronted him with her suspicion that he had taken another wife, the man placed a sickle around her neck, threatening murder. Ruqoyyah was eventually sheltered by activists.

Ruqoyyah said such experience had strengthened her commitment to help women. Today she is a nyai (a title for female religious leaders in Java), leads a pesantren (Islamic boarding school) and educates the surrounding community on ending domestic abuse and child marriage, which is prevalent in the area.

She dismissed the view that girls were ripe for marriage once they menstruated.

“How can keluarga sakinah [a harmonious family] be achieved with child brides?”

Responding to a tearful woman who said she had been forced to prepare her own deaf niece to marry her rapist, who had impregnated her, Ruqoyyah said victims should not be forced to marry their rapists.

She recalled how she had accompanied a girl for an abortion following rape by the girl’s own grandfather. She said the midwife had earlier refused the grandmother’s request for an abortion, fearing sin, but Ruqoyyah had convinced her that abortion of a pregnancy caused by rape was not sinful.

Women united: Zainah Anwar of Malaysia (left to right), Siti Ruhaini Dzuhayatin of Indonesia, Kamala Chandrakirana as the moderator, Bushra Hyder Qadiems Lumiere of Pakistan and Hatoon Al-Fassi of Saudi Arabia speak at a plenary session during the congress.

(JP/Nurul Fitri Ramadhani)

Women united: Zainah Anwar of Malaysia (left to right), Siti Ruhaini Dzuhayatin of Indonesia, Kamala Chandrakirana as the moderator, Bushra Hyder Qadiems Lumiere of Pakistan and Hatoon Al-Fassi of Saudi Arabia speak at a plenary session during the congress.

(JP/Nurul Fitri Ramadhani)

Extreme cases of objectification of women amounted to the “disappearance of true Islamic justice for women,” said lecturer Nur Rofiah, one of the speakers at the congress. Dakwah, or religious propagation, by these female clerics was their main strategy to end the injustice.

And some nyai have their own ways to reach that goal. Nyai Shinto Nabilah Asrori of Magelang, Central Java, for instance, reaches out to students and community members through her composition of Javanese tembang songs.

One song about relations in marriage says: “A man of dignity/ does not bark at his wife/ together they discuss/...”

The host of the international event, Nyai Masriyah Amva, 56, candidly shared her struggles to prove the worth of a female religious leader.

Following a divorce and the death of her second husband, the charismatic leader of the Kebon Jambu Al-Islamy Islamic boarding school said she had finally stopped “looking for a man to lean on.”

“I’ve found him – it is Allah,” she had told her students. Typically santri (students) leave when they feel the pesantren leaders leave – and Masriyah said she had been panicked.

But eventually she proved that a woman could do it “even better” with the Kebon Jambu Al Islamy school expanding both in size and student numbers under her leadership.

Masriyah has shared her stories in almost 20 books, one of which, titled Bangkit dari terpuruk (Rising after a fall), was sold out at the event.

In her books, she comments on discrimination of female religious leaders.

“While kyai are expected to take many wives, a religious female leader must be angelic; thus the status of a divorced widow, and then a widow by death, is utterly painful,” she said.

Masriyah also shared how the credibility and integrity of herself and the boarding school were at risk when rumors were spread that she had a crush on a man around her son’s age.

Even though the role of female pesantren leaders is still debatable, speakers at the congress believed that female clerics were often more directly engaged with the grassroots than male clerics and intellectuals, making their voices the most valid against patriarchal views. However, there are too few of them, especially those with a solid educational background.

Signing in: Local and international participants register themselves before attending the congress. (JP/Nurul Fitri Ramadhani)

Signing in: Local and international participants register themselves before attending the congress. (JP/Nurul Fitri Ramadhani)

Neng Dara Affiah, for instance, is probably the only female pesantren leader that is also a former member of the National Commission of Violence against Women and a PhD graduate of political and social sciences at the University of Indonesia.

While a pesantren leader must solve all problems at the school and community level, the challenges for women are even greater, more so for those considered rebellious.

“Loneliness” is the greatest challenge of a nyai, Neng Dara believes.

Welcome to city of ‘santri’ and saints

“Welcome to kota santri [city of Islamic students],” Netty Prasetyani, the wife of West Java Governor Ahmad Heryawan said, greeting participants in Indonesia’s first Congress of Women Ulema in Cirebon.

Both the municipality and the regency of Cirebon, around 220 kilometers from Jakarta, are among the founts of Indonesia’s Islamic heritage. Like the neighboring city of Banten, also in West Java, Cirebon hosts centuries-old pesantren (Islamic boarding schools) along with religious figures and santri who took part in the struggle against colonial rule.

The rector of Syekh Nurjati Cirebon Islamic State Institute, Sumanta, said a Cirebon sultan, Fatahillah, seized Batavia, later Jakarta, from Dutch rule. “This is where Islam […] spread across West Java,” Sumanta added.

Syekh Nurjati, Cirebon’s pioneer in religious propagation, was known to be close to Sunan Gunungjati, one of the Wali Songo, the pioneers of Islam in the archipelago who are considered saints.

Cirebon also hosts many Islamic schools, universities and institutions in addition to hundreds of pesantren. The congress venue was the Kebon Jambu Al Islamy boarding school in Babakan Ciwaringin district, a center for many pesantren in the past three centuries. Neighboring schools also helped the historic event, by among other things providing accommodation for visitors.

Rhythm of life: A man beats a bedug (traditional drum) at the Great Mosque of Cirebon. (Tribunnews/Herudin)

Rhythm of life: A man beats a bedug (traditional drum) at the Great Mosque of Cirebon. (Tribunnews/Herudin)

Rosidin, the executive director of Fahmina Institute in Cirebon, said the regency’s santri “come from across the country, even neighboring countries, such as Malaysia.”

Many santri are sent to Cirebon by parents who were alumni of Cirebon pesantren, he added.

Even as graduates spread elsewhere, others wish to continue religious studies in their former pesantren while attending higher education, Rosidin said. State and private Islamic higher learning institutions have set up branches around pesantren to facilitate such needs.

Many alumni cite their youth in pesantren under strict teachers and long hours of studies from dawn to late at night as their best years. One popular portrayal of pesantren life is the film Negeri 5 Menara (Land of 5 Towers), based on the novel by a graduate of the famed Gontor pesantren in Central Java, Ahmad Fuadi.

Recently the Buntet pesantren in Cirebon, with thousands of its students, was in the spotlight during the visit of President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo.

One alumnus of another Cirebon pesantren, Chozin Nasuha, wrote that the evolving needs of modern education contributed to the closure of many local pesantren - those that mainly depended on the traditional charisma of their male leader, or kyai.

Many kyai initially opposed the teaching of the modern curriculum, which they said was “like [that of] the Dutch” colonial system, Chozin explained.

“But then the regional administration saw it was problematic not to let students learn the national curriculum,” Rosidin said. Without diplomas, many graduates became jobless. Therefore, since the 1980s the Islamic schools have started to teach the formal curriculum.”

Solemn space: People pray and rest inside the Great Mosque of Cirebon, West Java. The mosque is one of the oldest in Indonesia. (Tribunnews/Herudin)

Solemn space: People pray and rest inside the Great Mosque of Cirebon, West Java. The mosque is one of the oldest in Indonesia. (Tribunnews/Herudin)

Today’s pesantren are no longer stigmatized as backward - but as bulwarks against extremist teachings. Like other areas, Cirebon has witnessed fierce contestation between “traditionalists” and “modernists”. However, old schools adopting modern curricula survive and attract more students. Popular pesantren seem to be those that combine quality secular curriculum and religious teaching with their leaders’ charisma and popular outreach beyond the schools.

Kebon Jambu Al-Islamy, the host of the international women’s ulema event, hosts over 1,000 male and female santri. It is run by its first female leader, Nyai (title of male clerics’ wives in Java) Masriyah Amva, who took over the school following her husband’s death.

A 10th grader of a nearby state Islamic senior high school, Fitriyani, who also studies religion at Kebon Jambu, said Nyai Masriyah tells sleepy students to focus, “otherwise, how can God give us what we want?” said Fitriyani.

Students shrieked with laughter while watching a documentary on their school and its leader – the camera caught santri dozing off in class or during prayers. No wonder – the first wake-up call is at 3 a.m. for night prayers, continued by Quran reading until the dawn prayers.

“She also tells girls to […] achieve all we want on our own,” said Fitriyani, who is from nearby Indramayu, which is among the regencies still struggling to reduce child marriage as a way to overcome poverty.

Pesantren leaders say they continue to educate local communities and students’ parents to allow children, particularly girls, to complete their educations.

Praying under the sky: Hundreds of Muslim women pray during the celebration of Idul Fitri in Denpasar Bali. (JP/Agung Parameswara)

Praying under the sky: Hundreds of Muslim women pray during the celebration of Idul Fitri in Denpasar Bali. (JP/Agung Parameswara)

| Producer | : | Ika Krismantari |

| Writer | : | Nurul Fitri Ramadhani, Ati Nurbaiti |

| Senior Managing Editor | : | Kornelius Purba |

| Managing Editors | : | Primastuti Handayani, Rendi A. Witular, M. Taufiqurrahman, Damar Harsanto |

| Desk Editors | : | Pandaya, Imanuddin Razak |

| Art & Graphic Design Head | : | Budhi Button |

| Photographers | : | Nurul Fitri Ramadhani, Arya Dipa, Agung Parameswara, Herudin |

| Technology | : | Muhamad Zarkasih, Mustopa, Sandy Riady Hasan, Sarah Naulibasa,

Ega Anugrah |

| Multimedia | : | Bayu Widhiatmoko |