Anti-vaccine movements gaining ground on the back of rising religious conservatism and the thriving internet are threatening to foil Indonesia’s painstaking effort to achieve its goal of 100 percent immunization. This worrying trend has seen the comeback of preventable diseases like diphtheria. The Jakarta Post’s Moses Ompusunggu and Ika Krismantari examine how the activism has undermined the immunization endeavor and how to counteract it. Hotli Simanjuntak in Banda Aceh, Syofiardi Bachyul Jb in Padang and Wahyoe Boediwardhana in Surabaya have contributed to this report.

Rika Restiana, a professional auditor in Padang, West Sumatra, believes solely in the power of breast milk and a healthy diet to protect her two children from diseases. She thinks there is no need to have them vaccinated.

“When a child contracts a disease, his or her immune system will defeat it. After my daughter survived a diphtheria outbreak, I still chose not to have my son vaccinated,” she told The Jakarta Post.

Rika was recounting a diphtheria outbreak that hit Padang in recent years, a predicament linked to the rising resistance against the state-sponsored immunization program largely for Islamic religious reasons. At the height of the outbreak in 2015, at least five children died from diphtheria, a disease that can be prevented by vaccination.

Since the introduction of the immunization program in 1956, Indonesia has been struggling to reach the 100 percent coverage to create immunity in the entire population.

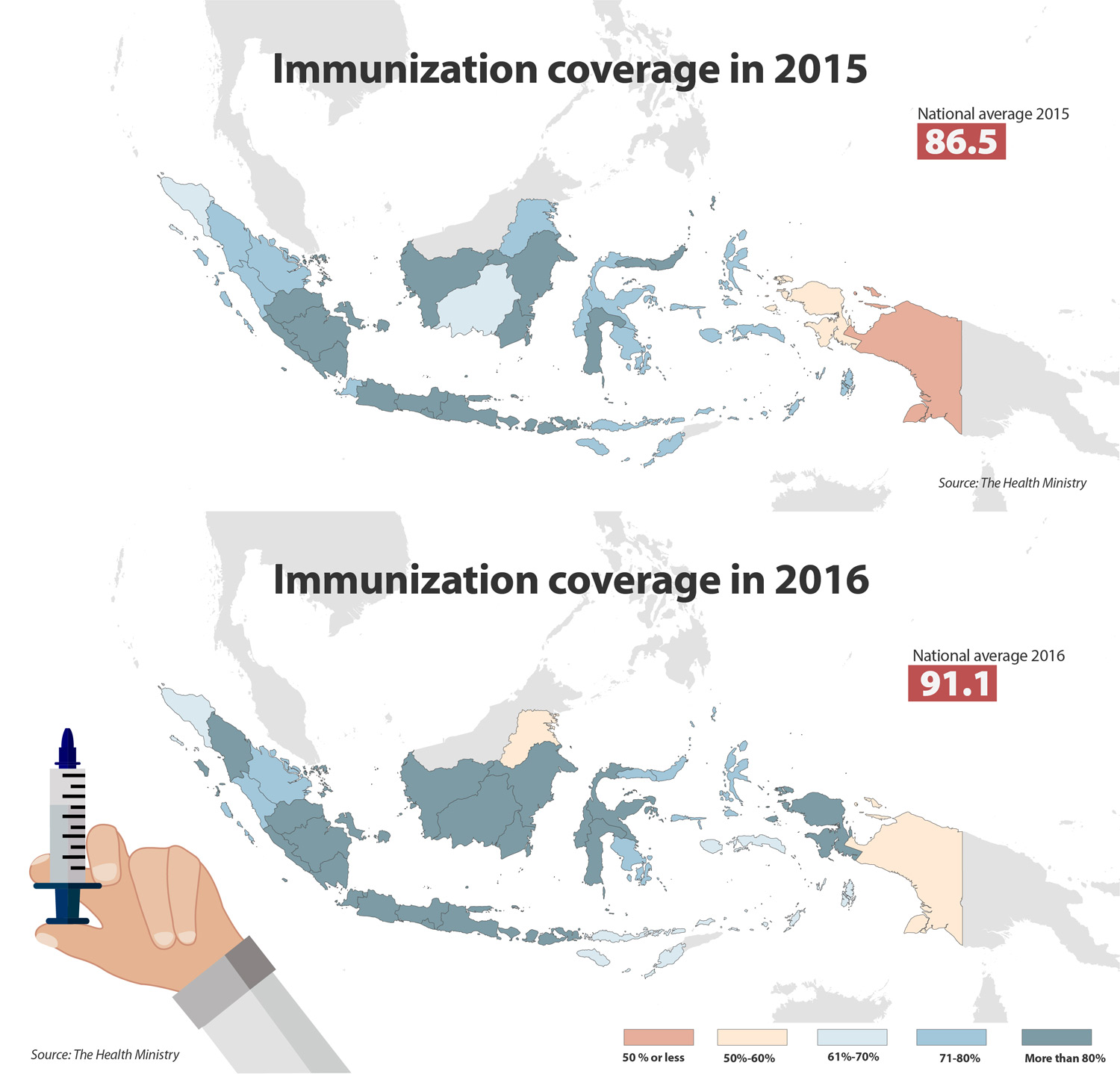

Health Ministry data show that 91.1 percent of Indonesian toddlers received basic vaccinations, including against tuberculosis, diphtheria, polio and measles in 2016, a slight increase from the 86.5 percent achieved in 2015.

Despite the improvement, the actual basic vaccination figures have persistently dropped since 2012. The downtrend has been blamed on distribution problems in remote areas, combined with the rising number of parents who repudiate nationwide vaccination.

The downtrend has been affirmed by Kenny Peetosutan, a United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) health specialist for immunization in Indonesia, based on her observation in the last 10 years, during which she has received reports of parents refusing vaccination shots for their children.

“Their number tends to increase, especially among those who have access to the internet, where they get information that changes their perception of vaccinations," Kenny said.

Resistance against immunization in Indonesia is evident from the negative response to the government’s newly launched Measles Rubella (MR) vaccination program among some segments of the population.

The strongest opposition comes from East Java. The province’s health agency has detected resistance against the vaccination program, which is an expansion of the mandatory measles vaccination in six regencies - Bangkalan, Sampang, Pamekasan, Sumenep, Ponorogo, and Jember. Hundreds of schools in East Java have openly rejected the scheme. They include 31 preschools, 118 elementary schools, 24 junior high schools and 23 pesantren (Islamic boarding schools).

East Java has a long history as a fertile ground for anti-vaccine views. Resistance against immunization existed in the province before it became a national program, driven by misconceptions surrounding vaccinations that the government has yet to adequately address, says East Java Education Council chairman Akh Muzzaki.

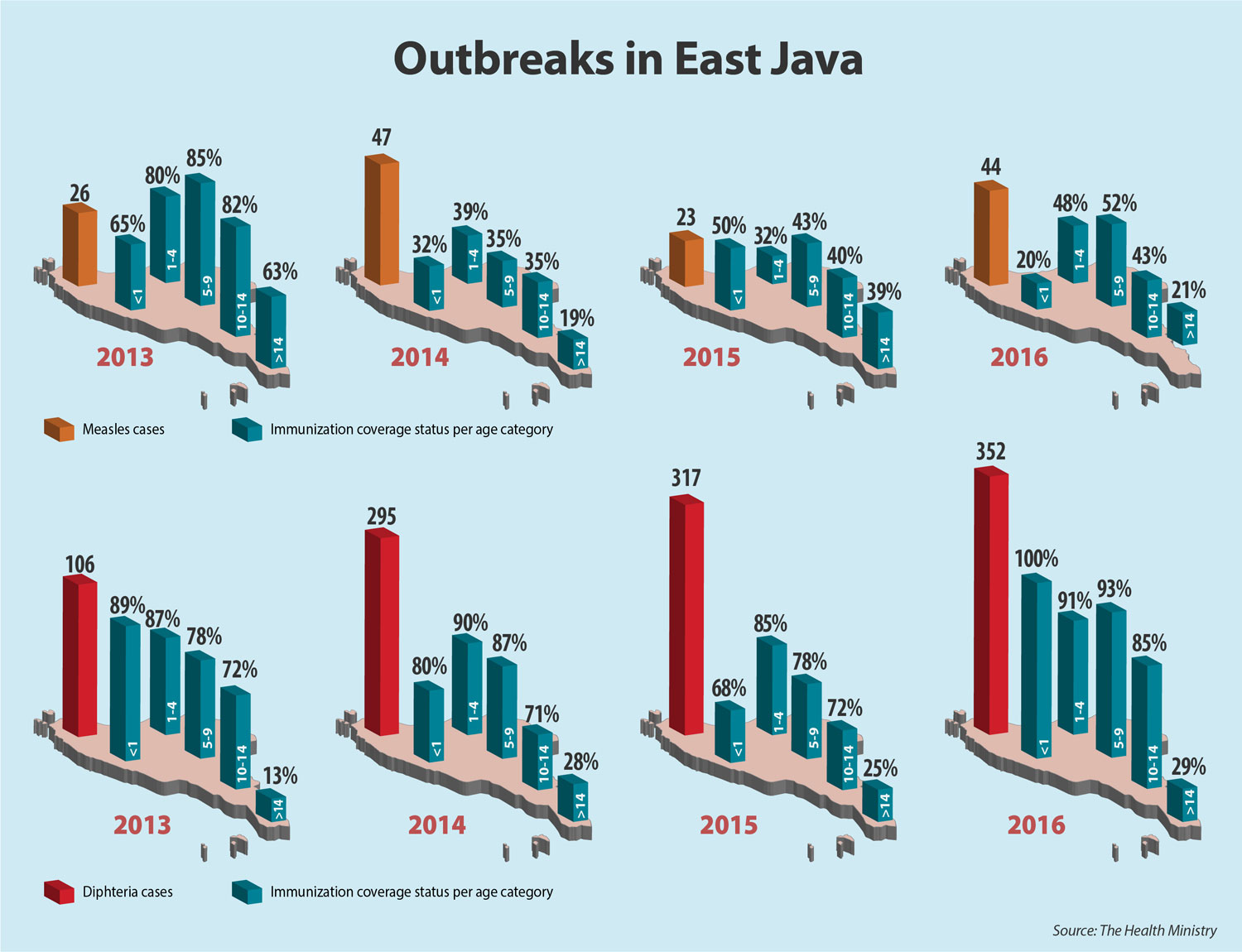

The repercussions have been quite devastating. The province has suffered from many outbreaks following the declining immunization coverage due to parents’ strong rejection.

At least 80 percent of the population of a region needs to be vaccinated to achieve a condition called herd immunity, which occurs when a large percentage of the inhabitants has become immune to certain infections. Less than 60 percent means an outbreak looms.

A diphtheria epidemic in East Java killed nine children in 2009, 21 in 2010 and another 11 in 2011. In 2011, the central government declared the outbreak in the province an “extraordinary occurrence” and provided Rp 8 billion (US$600,736) in relief aid.

The East Java case, according to Kenny, is an example of how a failed vaccination program not only burdens families, with their children exposed to diseases that can cause paralysis and death, but also weighs on the state.

Health experts are calling on the government to take the anti-vaxxers seriously, even though the nationwide immunization coverage is well over 80 percent, otherwise their campaigns may disrupt the national program.

"We should never think that Indonesia is already free from preventable diseases,” Indonesian Pediatricians Association general secretary Piprim Basarah Yanuarso said, underscoring that complacency was a major factor behind massive outbreaks in foreign countries like Russia in the early 1990s.

As Kenny points out, the immunization program should equally cover all regions. “If people refuse immunization, we run a risk of disease outbreaks,” she said.

Another region highly vulnerable to rubella and measles outbreaks is Yogyakarta, where resistance against immunization is gaining traction. Over the past two years, the province has had a basic vaccination rate above the national average.

But last year, the province recorded 176 cases of rubella and measles. The number is expected to rise after eight schools in Yogyakarta have refused to take part in the ongoing MR vaccination program, alleging the vaccine contains substances forbidden by Islamic law.

Who are the anti-vaxxers?

Basically, there are two categories of anti-vaxxers in Indonesia. The first are those who base their arguments on Islamic dogmas and the second are “naturalists” who believe that immunity is something the human body can build naturally with a healthy lifestyle.

The Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) says the puritan people in both groups believe that vaccination is against the concept of “life submission" to God, or that the vaccine contains a pork enzyme forbidden in Islam.

MUI's fatwa commission secretary Asrorun Niam says such views are common in conservative Muslim-majority provinces like Aceh, West Sumatra, East Java, Banten and West Java.

Piprim says, "Until now, there are still a lot of people […] who reject vaccines out of a belief that they contain a pork enzyme."

Based on this conviction, the basic vaccination coverage in Aceh, the only province that has formally adopted the sharia, was 69.1 percent last year, way below the 80 percent set by experts to achieve the herd immunity condition.

West Sumatra is another province where the vaccination rate is below 80 percent. In 2013, the coverage dipped to 35 percent.

With a low immunization coverage, these deeply religious regions have frequently suffered outbreaks. Ninety-three cases of diphtheria were found in Aceh between 2013 and 2017. The disease also broke out in West Sumatra last year with 110 cases reported, an increase from 9 cases in 2015.

A major measles outbreak also occurred in West Java and Banten in 2015. Last year, East Java became the center of a national diphtheria epidemic, with 62.6 percent of the infections happening there.

Unlike devout Muslims, who are usually concentrated in one area, the naturalists are scattered, and they use the internet to spread their ideas.

Piprim identifies these naturalists as mostly educated people from the middle economic bracket, even though he does not rule out that equally educated people can also be found in religiously motivated anti-vaccine groups.

The anti-vaxxers’ profile, as Piprim describes, matches results of the 2013 national basic health survey, which concluded that resistance against immunization came from certain groups of well-educated middle and upper-class people.

Watch and learn: Students watch a health worker prepare a syringe during an immunization program at an elementary school in Lhokseumawe, Aceh.(Antara/Rahmad)

Watch and learn: Students watch a health worker prepare a syringe during an immunization program at an elementary school in Lhokseumawe, Aceh.(Antara/Rahmad)

How they preach

In Indonesia, anti-vaxxers work using both online and offline platforms, targeting different audiences. They turn to Internet forums and social media to reach people of middle-class economic standing, while addressing the less educated in small religious gatherings in mosques or private homes.

Interestingly, they work mostly under cover. They don’t explicitly state that they are against vaccination; instead they use different language to deliver their message. For example, participants of an online group would identify themselves as “breastfeeding supporters”, yet they focus their conversations on anti-vaccine topics.

They seem to have learned a lesson from the failure of the first anti-vaccine seminar in 2012. Held in Yogyakarta, the event was the first of its kind to publicly declare anti-vaccine views. The seminar was later countered by the pro-vaccine camp.

Other efforts include publishing books containing anti-vaccine views. The Post recently discovered copies of such publications at a second-hand book center in Blok M Square, South Jakarta.

Mother’s inquiry: The mother of baby Irsyad Fachr (right) demands an explanation from a private mother's and children's hospital in East Jakarta on a rumor about fake vaccines reportedly distributed at 14 private hospitals in Jakarta. (JP/DhoniSetiawan)

Mother’s inquiry: The mother of baby Irsyad Fachr (right) demands an explanation from a private mother's and children's hospital in East Jakarta on a rumor about fake vaccines reportedly distributed at 14 private hospitals in Jakarta. (JP/DhoniSetiawan)

The fact that many parents like Rika in Padang have fallen under their spell shows how effective the anti-vaccine activists’ strategies can be.

Rika said she was convinced after she had read an article about a conspiracy behind the production of vaccines. It insinuates that the purity of the ingredients was not guaranteed and that they may contain pork enzymes or prisoners’ blood.

“I'm sure not having [my children] vaccinated is the right thing to do,” she said.

Too hurtful to look: An elementary school child closes her eyes when she is given a measles vaccine at her school in Palembang, South Sumatra.(Antara/FenySelly)

Too hurtful to look: An elementary school child closes her eyes when she is given a measles vaccine at her school in Palembang, South Sumatra.(Antara/FenySelly)

In painstaking pursuit of children’s health

This year’s two-month measles-rubella (MR) vaccination campaign launched on Aug. 1 is somewhat extraordinary in every regard. Costing Rp 893 billion (US$669,466), it is touted as the world’s second-biggest after that in India. The launch was attended by President Joko Widodo, whose presence demonstrated his determination to free Indonesia from the two infectious viral diseases by 2020.

And it took place in Yogyakarta, which happened to be in the media spotlight after eight schools, suspecting the presence of pork products in the vaccines, refused to participate in the national program, causing fear of an imminent outbreak in the province where religious conservatism is taking hold.

The anti-vaccine movement, driven mostly by religious beliefs, has caused widespread concern in Indonesia, which has seen sporadic yet deadly outbreaks of diphtheria, rubella, measles and polio over the past decade or so.

The Health Ministry's director for surveillance and quarantine, Elizabeth Jane Soepardi, is among those apprehensive about the antivaccine propaganda that has been amplified not only by hard-line preachers but also some academics and celebrities. "Negative campaigns against vaccination are likely to intensify," she said.

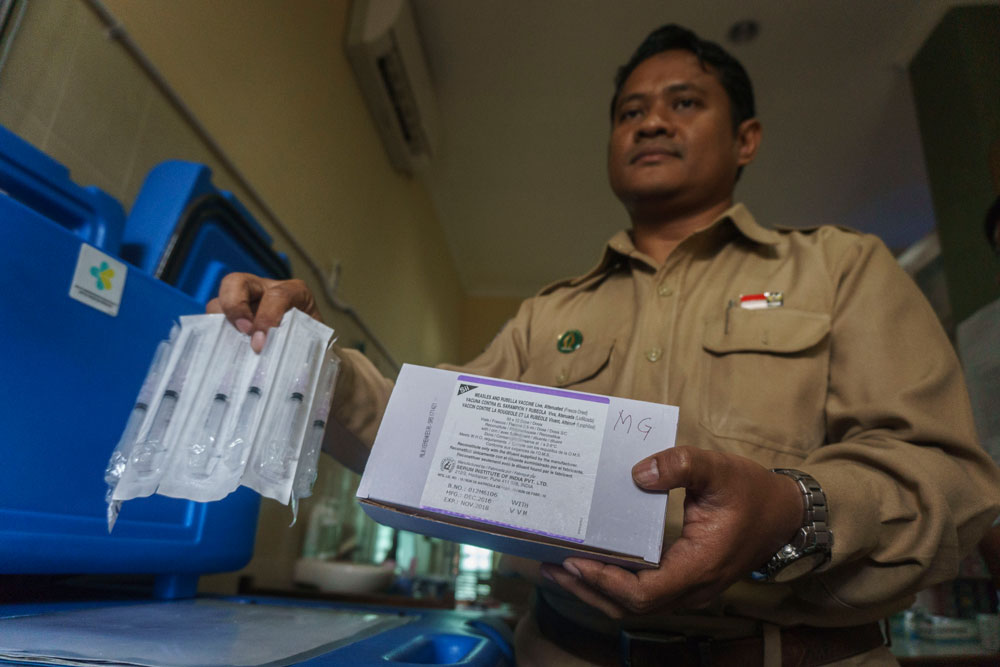

Needle man: The head of Mergangsan community health center in Yogyakarta shows measles and rubella vaccines at his office. The government launched the nationwide measles and rubella vaccination in early August in an attempt to be free from the diseases by 2020 . (Antara/HendraNurdiyansyah)

Needle man: The head of Mergangsan community health center in Yogyakarta shows measles and rubella vaccines at his office. The government launched the nationwide measles and rubella vaccination in early August in an attempt to be free from the diseases by 2020 . (Antara/HendraNurdiyansyah)

Nevertheless, the nationwide immunization drive, which was a big success during the 32 years of the authoritarian New Order regime, looks set to march on with the help of UNICEF and the World Health Organization (WHO). The world organizations have assigned four monitors to help oversee this year’s campaign.

Aware of the strong religious overtones among the opposition camp, over the past 60 years government officials along with health activists have courted Islamic religious leaders for support. Their effort eventually appeared to pay off. Last year the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) issued a fatwa allowing vaccinations.

The much-applauded edict acknowledges vaccination as a permissible effort to avoid life-threatening maladies. It may become mandatory for people who need vaccines for the purpose of saving their lives. So today Muslims willingly receive anti-meningitis shots before they depart for Mecca to perform the haj.

The MUI edict is an important development that has boosted the immunization drive although the actual compliance scale among the diverse Muslim community is yet to be seen. Besides, immunization advocates have also joined hands with more traditional Muslim organizations like Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), Indonesia’s largest Islamic group.

Simultaneous shots: Children are given vaccines at Insan Kamil elementary school in Bogor, West Java. (Antara/Arif Firmansyah)

Simultaneous shots: Children are given vaccines at Insan Kamil elementary school in Bogor, West Java. (Antara/Arif Firmansyah)

Indonesia has made immunization mandatory. A 2005 Health Ministry decree on the provision of vaccines guarantees their safety and makes antivaccine activism illegal. However, the law is yet to be properly enforced.

Critics like Akh Muzzaki, the East Java Education Council chairman, say that the immunization campaign program is also poorly executed.

Muzzaki believes that the antivaccine movement thrives because the government had been too sluggish in handling the issue until the MUI came out with the fatwa. East Java is well-known as a hotbed for conservative Muslims who reject vaccination.

“Immunization has not become part of our tradition yet, especially among ‘pesantren’ [boarding school] people. They don’t really understand how immunization can usher in a healthy life,” Muzzaki told The Jakarta Post.

What the government can do to improve citizens’ awareness about the need for immunization in East Java is more engagement, rather than just waging an information campaign through leaflets and circulars.

A tactic that Muzzaki would like to see is government representatives involving Muslim organizations in the campaign. Together they can make vaccination part of the local tradition in the long run.

A different perspective comes from Indonesian Pediatricians Association general secretary Piprim Basarah Yanuarso, who wants the government to engage doctors who have sound theological knowledge in its immunization campaign in deeply religious regions where vaccine opposition is strong.

"We have to speak in their language," Piprim argues. “Furthermore, not all clerics with the Indonesian Ulema Council have a sound understanding of the science of vaccination.”

Handfed: A child is given a polio vaccine during National Immunization Week in 2016 in Bandung, West Java. (JP/Arya Dipa)

Handfed: A child is given a polio vaccine during National Immunization Week in 2016 in Bandung, West Java. (JP/Arya Dipa)

Another weak area that the government will have to address is the monitoring of vaccine distribution. This problem leads to the low immunization coverage in far-flung and sparsely populated regions like Papua.

The fake-vaccine scandal in 2016 highlighted the authorities’ failures in monitoring the quality and the distribution of vaccines. It eroded public confidence in vaccinations and has been exploited by the anti-vaccine groups to promote their views.

Fortunately, the government was quick enough to repair the damage, overhauling the vaccine-monitoring system and prosecuting the fake-vaccine makers and distributors.

Lessons from other countries

Indonesia is not the only country dealing with antivaccine movements. Others like Pakistan and Afghanistan are also struggling to meet their immunization-coverage targets largely because of political and security issues.

Western Europe and the US are also dealing with religiously charged antivaccine activists. Some countries have issued strict regulations to punish parents who refuse vaccinations for their children.

Countries like Italy and Germany have made vaccinations mandatory, imposing penalties on vaccine-recalcitrant parents. In Germany, parents who fail to have their child vaccinated are liable to a fine of 2,500 euros ($ 2,948). Italy recently passed a law that mandates 10 vaccines for kids up to 16 years old and requires parents to prove their children are immunized before enrolling at school or be fined 500 euros.

Blind pain: Students line up for immunization shots in Madura, East Java. (Antara/SaifulBahri)

Blind pain: Students line up for immunization shots in Madura, East Java. (Antara/SaifulBahri)

There is a serious doubt that such policy could be applicable in Indonesia, where immunization is compulsory but the law carries no sanctions for parents who flout it. Elizabeth is floating an idea of involving the Indonesian Child Protection Commission in the immunization program to make it more effective.

Another strategy worth trying is to make people’s participation in the immunization program a prerequisite for school enrolment as in countries like Australia. Down Under, parents must provide their children’s immunization record before they can enroll them at school. In addition, parents with unvaccinated children are not eligible for child-care benefits.

The Australian model has been started in Jakarta, where some international and local private schools have asked parents to show their children’s immunization reports.

In view of all the challenges, it would obviously take some time before Indonesia can strictly enforce the law that makes immunization mandatory.

Needle fear: A female elementary student in Lhokseumawe, Aceh, is about to receive an immunization shot from a health worker while other students watch.(Antara/Rahmad)

Needle fear: A female elementary student in Lhokseumawe, Aceh, is about to receive an immunization shot from a health worker while other students watch.(Antara/Rahmad)

| Producer | : | Ika Krismantari |

| Writer | : | Moses Ompusunggu, Hotli Simanjuntak, Syofiardi Bachyul JB,

Wahyoe Boediwardhana |

| Senior Managing Editor | : | Kornelius Purba |

| Managing Editors | : | Primastuti Handayani, Rendi A. Witular, M. Taufiqurrahman, Damar Harsanto |

| Desk Editors | : | Pandaya, Imanuddin Razak |

| Art & Graphic Design Head | : | Budhi Button |

| Photographers | : | Donny Setiawan, Arya Dipa |

| Technology | : | Muhamad Zarkasih, Mustopa |

| Multimedia | : | Rian Irawan, Ahmad Zamzami, Ricky Yudhistira,

Jessica Widharta, Anggit Muhammad |