Although in the West it began as early as the 18th century, stand-up comedy made inroads into Indonesia only in the 1990s. The Jakarta Post’s writer Corry Elyda discusses how the local folklore tradition and the burgeoning TV industry have shaped the comedy genre into popular entertainment. Our correspondents Arya Dipa in Bandung, Andi Hajramurni in Makassar and Hotli Simanjuntak in Aceh contribute accounts of how the art of joking is finding its way to the regions.

Until seven years ago, event organizers would rely on music and dance to liven up parties. Things began to change with the rise of stand-up comedy, which quickly gained popularity thanks to its steady stream on TV.

Stand-up comedy reached a turning point in 2011 when two TV stations held competitions. Kompas TV staged Stand-up Comedi Indonesia (SUCI) and its competitor Metro TV produced Stand Up Comedy Show and Battle of Comics. The public response was simply overwhelming. Soon, more stations set the stage for funny masochists to compete. The much-coveted rewards are fame, celebrity status and, of course, money for those who can make the audience guffaw – and career graveyard for those whose jokes leave the crowd yawning.

Successful comics like Ernest Prakarsa, Mohamad Ali Sidik aka Mosidik and Sakdiyah Ma’aruf have risen to the next level as movie personalities and international performers in a relatively short span of time, something rarely seen before.

Solo comedy began taking root in Indonesia in the 1950s, when radio still ruled the airwaves as the main infotainment media. Comedy competitions were often held back then. Those making names for themselves as solo comedians were Bing Slamet, Ateng and Iskak – to name a few. But in their prime years, they eventually formed groups, leaving the monologue art to fade from the limelight.

Iwel Wel, the entertainer widely recognized as Indonesia’s first stand-up comedian, who learned about the art through videos and books, recalls that between the 50s and the 90s, solo comedy was not quite the same as the stand-up comedy we know today.

Solo comedy, he explains, has no ''rules'' in that actors were free to choose their topics and present them to their audiences, while stand-up comics are bound by a set of standards and follow certain techniques.

As a pioneer, Iwel’s career was not that distinguished. He would struggle to find cafes that were kind enough to allow him to perform. Often, he took all the trouble to explain to the bewildered management of the establishments what stand-up comedy was all about.

After several years, Iwel decided to hold a solo off-air stand-up show, which he claims was the first of its kind in the country, at the Gedung Kesenian Jakarta (GKJ) in March 2004. The performance was a milestone in his career.

“Thanks to media coverage, Indonesia became more and more familiar with stand-up comedy,” he says. The show prepared his way to TV stations, which made his artistic journey easier.

Another personality worth mentioning as a stand-up comedy trailblazer in Indonesia is Ramon Papana, a former disk jockey who passionately studied the art in the United States.

Back in Indonesia, Ramon opened a comedy cafe in Kemang, South Jakarta, in 1997 and cajoled anyone, including his employees, to practice telling jokes on the coffee bar’s stage, an exercise internationally called open mic.

Renowned comedians Tukul Arwana and the late Taufik Safalas were among his employees. “I wanted them to become stand-up comedians, but they ended up being traditional comedians,” he said.

In today’s internet era when entertainment is at one’s fingertips, marketing becomes easier with hugely popular media like YouTube. So the more tech-savvy millennial comics like Pandji Pragiwaksono and Raditya Dika know only too well how to promote their materials. They upload their open mic sessions to YouTube.

When Kompas TV courageously opened the first national stand-up comedy competition in 2011, stand-up comedy was only budding as a showbiz. Called SUCI, the contest proved hugely popular and continues until today.

“Back then, it was difficult to get participants for the first season of SUCI,” says Pandji, a host who was involved in the birth of the program along with producer Indra Yudistira. On the jury were, among others, comedian Indrodjojo Kusumonegoro, better known as Indro Warkop, and versatile actor Butet Kertaradjasa, dubbed Indonesia’s “King of Monologue”.

As Indonesians are quite familiar with folklore and passing jokes on by word of mouth, stand-up comedy rapidly gained popular acceptance by all spectrums of society. Competitions are no longer short of participants and loyal crowds.

Almost all the big names in the Indonesian stand-up comedy scene, like Ernest Prakarsa, Mosidik and Kemal Palevi, honed their skills in competitions and are “alumni” of SUCI. Other TV stations like Metro TV and Indosiar have since created their own programs dedicated to promoting stand-up comedy.

Off air, many stand-ups with a national reputation have been trying their luck in movies, talk shows, variety shows, commercials and even YouTube.

So popular is stand-up comedy in Indonesia today that such public figures as then-Jakarta governor Basuki “Ahok” Tjahaja Purnama would often be seen employing jesters’ techniques when delivering speeches, as did former US president Barack Obama. To boost his public persona, Ahok and Bandung Mayor Ridwan Kamil tried their hand at stand-up comedy on TV during a talk show last year. In their crowd was vice president Jusuf Kalla.

“The fact that stand-up comedy is still thriving after seven years proves that it is becoming a trend, not just euphoria,” said Ernest, who wears another hat as a film director.

While most comics make a name for themselves at home, Pandji and Mosidik have gone international. So far, Pandji – under his tagline of Juru Bicara (Spokesman) has toured 24 cities both in Indonesia and other countries, like Germany, Japan, the US and Australia. In his world tours, his audiences are mostly Indonesian communities, so his medium of communication is the Indonesian language.

But Mosidik, as a former radio presenter and an SUCI finalist, is confident enough to tell his jokes in English when performing overseas.

“I started doing open mic in neighboring countries like Malaysia and Singapore. At first, I got three to five minute sets. It took me two years before I could make money from it,” he says. Now, he makes more than Rp 10 million (US$750) for every 20-minute show.

His tenacity and ability to break language barriers have paid off. He is the first Indonesian to have performed at the prestigious Comedy Central Asia. This year, he will take part in an international stand-up comedy festival in Edinburgh.

“I have always been honing my English,” he says. “My favorite material is my being fat, because overweight is a universal issue,” he said, chuckling.

While comedy is not yet established as an industry, the art is burgeoning, with communities sprouting in every corner of the archipelago. Called Stand-up Indo, the community cofounded by Pandji and Ernest has mushroomed in places as far away as Bontang in East Kalimantan and Buton in Southeast Sulawesi, Jakarta and Cilegon in Banten. Members make the most of open mics at cafes and other public venues in their areas.

Once in a while, more established comedians lend a hand, too. Ernest, for example, would pick cities and towns that already have a stand-up community whenever he has the chance to perform off-air. “Dropping in on them while on tour to the region is a form of moral support I can give them,” he says.

Although comedy continues to grow, the actors predict it will take quite a while until it becomes an industry. A major problem they commonly encounter is people’s reluctance to pay reasonably for a show – well at least by entertainers’ standards. Pandji, for instance, charges Rp 500,000 for an entrance ticket to his gig and is planning to raise it.

“Although people like our jokes and more jobs are landing on our comics, this is yet to translate into adequate income,” Pandji says. “People are unwilling to pay a little more.”

That is why most comics still rely on other jobs, often outside the entertainment industry, for steady income. Comic Sakdiyah Ma’aruf, for example, has unwavering loyalty to stand-up comedy but she has to double as an interpreter, a speaker and a translator.

“Through stand-up comedy, I can talk about my weaknesses and my concerns about the present situation while making people laugh together,” she says.

For Sakdiyah, who was born and raised in a conservative Arab-Indonesian family, stand-up comedy is a medium that allows her to speak up on sensitive issues like extremism and sexism that concern her.

“Comedians don’t mean to preach but ask for people to reflect on common issues,” says the hijab-clad woman who won the prestigious Vaclav Havel Prize for Creative Dissent in 2016.

Just like their fellow comics in the West, Indonesian stand-ups also make the best of their jokes to raise sociopolitical issues and criticize the system. They use the stage to air their political views, and they never run out of materials, especially during election campaigns.

But in Indonesia, where democracy is far from mature and political as well as religious issues are often highly sensitive, comedians have to toe the line or risk backlash, because somebody out there who is not amused by the satire may file a criminal report. Pandji has been reported to the police several times for poking fun at public figures, but police are apparently among his fans and found nothing offensive about his jokes. In another incident, a rookie stand-up received a death threat for making fun of the sharia in Aceh, after his show was posted on YouTube.

Now, Indonesian stand-ups play it safe, choosing non-sensitive issues, and so do broadcasters, which prefer to air recorded performances and avoid live.

People in showbiz see bright prospects. Ramon, recently opened the Indonesia School of Comedy. “Stand-up comedy can be a breeding ground for many other professions like presenters, actors, directors and motivators. ”It keeps growing,” he says.

Homegrown comics take center stage

The clock struck 8:30 when the “Superman” anthem began to play. Two portly hosts, Gian Luigi and Kunkun Kurniawan, rushed onto the stage amid a hail of clapping and cheering that filled the Bober Café in Bandung, as it began its routine open mic for stand-up rookies.

Open mic is a universal live show tradition usually observed at coffee houses, pubs, nightclubs or comedy clubs, where amateur and professional stand-up comedians seize the opportunity to practice and test their materials before they qualify for the big stage.

That night, about 20 young people, mostly in T-shirts and some donning baseball caps, assembled at two tables at the left side of the stage. Each of them was nervously waiting for their turn to appear on stage and be the funniest guy of the night. As the hosts were speaking and participants taking turns to perform, they were busy planning their jokes.

The first aspiring stand-up striding to the stage was a security guard named Aep. In a performance punctuated with lots of false starts, he joked about how difficult it was for him as a security officer to date a girl, because women were afraid he would hardly have time for fun together.

“They think I would only take them for a stroll around the housing complex,” he said.

Silence.

He managed to set off some laughter when he promised to feed his wife, once he’d have one, rice rather than the truncheon, no matter how poor he might be. “It would be just like [the local famous cleric] Aa Gym and [celebrity motivator] Mario Teguh, who certainly feed their wives rice rather than Quran verses and motivational words.”

Next, Raka, a 20-year old geography student of the Indonesian Education University of Bandung grabbed the mike. Wearing a cold, unsmiling face, his jokes worked quite well. He began with one about the notorious student brawls. Then he confessed that he had no girlfriend yet. But he was proud to talk about one romantic moment when he was holding hands with a beautiful girl… “That was when we were introducing ourselves.”

Bintang Emon made fun of his own short frame that made him much shorter than his little brother. His friends suggested that he swim more to increase his height.

“I wouldn’t buy their stories. You know why? Jellyfish swim day in day out, but they remain short and soft.” He burst out laughing at his own punch line, but the audience remained cold. He realized it is a no-no to repeat a joke, no matter how funny it may be.

Founded in 2011, Bandung’s stand-up community is one of the most active in the country, holding regular open mics at local cafes. To hone their skills, members also hold discussions every Friday, where they exchange expertise and experience.

Some of the big names born out of this community are Mosidik, Budi Kusuma and Ge Pamungkas. They leaped to the national stage after winning competitions organized by TV stations in Jakarta.

The Bandung community leader, Gusman Suherman, 29, is proud the organization remains active after six years. “We have around 50 members now, the youngest being an elementary school student and the oldest a man in his 50s,” he says.

The comedy fever followed stand-up competitions staged in 2011 by Kompas TV (Stand-Up Comedi Indonesia, or SUCI) and Metro TV (Stand Up Comedy Show and Battle of Comics). Now, it has swept far and wide. Major cities across the archipelago have set up their own communities that flourish because the comedy genre is well received.

Stand-up Comedy Indonesia Makassar in South Sulawesi, for example, already gets gig offers from various quarters. Offers usually come in July, when schools celebrate graduations. Even the more serious organizations, like the military, need comedy for a good laugh during certain events.

“The number of job offers to both the community and its members has increased over the years,” says local comedy community leader Sri Rahayu, a 2014 SUCI finalist.

Despite the growing popularity, local comedians – just like their fellows elsewhere in the country – cannot yet make enough money to support their families and therefore treat the art as a side job. Besides, as most of the members take it up as a hobby, they use part of the proceeds from the shows to fund their club’s activity.

Stand-up comedians have found South Sulawesi to be fertile ground, largely because the ethnically diverse province is already rich in folklore handed down from generation to generation. Major townships, such as Gowa, Maros and Pangkep, have set up their own stand-up communities.

The art is even gaining ground in Aceh, the devout Islamic province, where folklore is losing out to modern forms of entertainment. Aceh Stand-up Comedy Indonesia Community leader Andhica Perkasa counts five townships that have formed clubs, although only about 15 of the 40 comics joining the communities are really active.

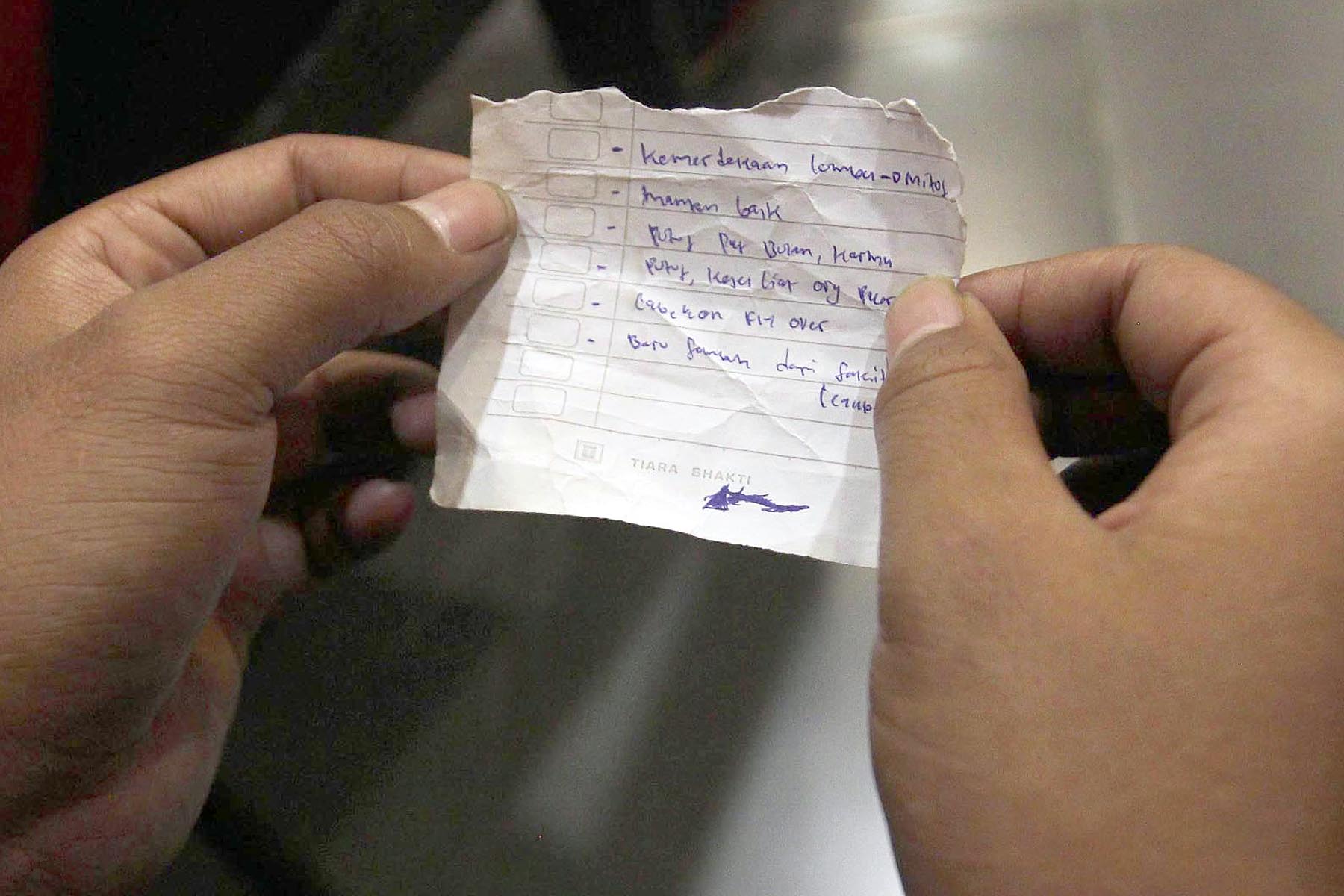

In Aceh, the only province to formally adopt the sharia and which has barely recovered from decades of armed secessionist conflict, picking safe topics for jokes is particularly challenging. Political and religious matters are practically off-limits. That is why stand-ups turn to the funny aspects of everyday routine as their materials.

“Issues surrounding religion, politics and past conflict should be avoided, so as not to spark a new conflict in the society,” Andhica says.

| Producer | : | Ika Krismantari |

| Writers | : | Corry Elyda, Arya Dipa, Andi Hajramurni, Hotli Simanjuntak |

| Senior Managing Editor | : | Kornelius Purba |

| Managing Editors | : | Primastuti Handayani, Rendi A. Witular, M. Taufiqurrahman, Damar Harsanto |

| Desk Editors | : | Pandaya, Imanuddin Razak |

| Art & Graphic Design Head | : | Budhi Button |

| Photographers | : | Ibrahim Irsyad, Jessica Widartha |

| Technology | : | Muhamad Zarkasih, Mustopa, Ega Agung Nugraha |

| Multimedia | : | Ahmad Zamzami |