East Nusa Tenggara (NTT) was on the verge of losing sandalwood, a premium commodity that Chinese traders came there for in the fifth century and European traders in the 18th century. Five years ago, the provincial government embarked on a campaign to save the endangered fragrant species. The Jakarta Post’s correspondent Djemi Amnifu in Soe looks into the present state of the slow-yielding plant and the prospects of the replanting effort.

In 1986, then East Nusa Tenggara (NTT) governor Ben Mboi issued a bylaw on the trade in sandalwood that everybody in the impoverished province has been regretting ever since; five years later it was revoked and replaced with a more populist one.

The ordinance asserted that every single sandalwood tree in the province belonged to the state even if it grew on private property; that anyone illegally cutting or neglecting them was liable to prosecution and in a case where it grew on private property, the land owner was entitled to only 20 percent of the proceed from the sales.

In the early 2000s, the people woke up to a sad reality: The once ubiquitous fragrant plants that made NTT famous all over the world disappeared. The precious tree neared extinction only 15 years after the bylaw went into force.

A red sandalwood tree. (Courtesy of Wikimedia commons)

A red sandalwood tree. (Courtesy of Wikimedia commons)

Official statistics show that in 1980, NTT shipped 15,000 tons of sandalwood. The volume plummeted to 100 tons in 2000, and in 2004 there was nothing left to be exported. Soon most sandalwood producers went out of business with the remaining few artisans relying on old limited stocks.

The state’s claim on sandalwood proved disastrous. The 20 percent share made people lose their sense of belonging to the precious trees. Some also regarded the plants as a curse. Frustrated, they destroyed young plants and sold the bigger ones at low prices.

In fact, the government’s claim to the sandalwood already began in the Dutch colonial era. The difference was that until 1986, the farmers had been entitled to a much bigger share of the sale value and thus resistance was low. For example, a 1966 bylaw set the villagers’ share at 50 percent.

In the wake of the 1986 ordinance, many people were arrested and prosecuted for harvesting wood handed down by their ancestors. Those opting for customary trials were compelled to pay hefty fines they had to pay in kind, especially in cattle and locally made woven sarongs.

Sign from the past: An old sign at a Tropical Oils plant in Kupang, East Nusa Tenggara. The company once exported its products to Singapore, Thailand, Hong Kong and China. (JP/Djemi Amnifu)

Sign from the past: An old sign at a Tropical Oils plant in Kupang, East Nusa Tenggara. The company once exported its products to Singapore, Thailand, Hong Kong and China. (JP/Djemi Amnifu)

Then, while the trade was controlled by the state, angry residents were out to destroy seedlings that grew in their land simply because they did not want to get into trouble when something went wrong with them. Combined with the slash-and-burn land clearing tradition as highlighted by Dutch researcher Meine van Noordwijk, the wrath of the villagers accelerated the tree’s extinction.

The government’s intervention in the business dealt small-scale businesses a heavy blow. The price was pegged at Rp 7,000 (52 US cents, at today’s rates) per kilogram of wood and retailers resold it at Rp 15,000 – Rp 25,000 per kg. Farmers no longer saw any economic value in sandalwood. When the commodity became scarcer, the black market thrived and sandalwood theft became widespread.

Abandoned: This sandalwood oil factory belonging to Tropical Oils in Kupang, East Nusa Tenggara stopped operating in 2000 due to lack of supply after more than 20 years of operation. (JP/Djemi Amnifu)

Abandoned: This sandalwood oil factory belonging to Tropical Oils in Kupang, East Nusa Tenggara stopped operating in 2000 due to lack of supply after more than 20 years of operation. (JP/Djemi Amnifu)

Roby Selan, a senior forestry official in South Timor Tengah regency, says thieves would dig up roots – the parts that contain the most valuable oil – and often leave the trees fallen and rotting.

The regency used to pride itself as being among the province’s main sandalwood producers, along with Sumba, Alor, Flores and Rote islands.

Myths

For centuries, world traders have sought sandalwood from NTT. Its oil is rich in medicinal properties and widely used as fragrance essence while its wood is suitable for upmarket furniture, incense used in religious rituals, beads, sculptures, fans and accessories like bracelets.

Until the 1990s, Indonesia exported sandalwood oil to Hong Kong, Singapore and Europe. Three decades ago, the export volumes reached 1,000 liters a year at $300 per liter. In 2000, the volume dropped to less than 300 liters. A milestone came in 2001, when PT Tropicana Oil bowed out of business because of raw-material shortages. In 2004, all exporters called it a day for the same reason.

In pieces: Sandalwood was one of the most expensive commodities of the last century. (Courtesy of Pixabay)

In pieces: Sandalwood was one of the most expensive commodities of the last century. (Courtesy of Pixabay)

In its heyday, sandalwood contributed significantly to the local government coffers. In 1987, the commodity accounted for 48 percent of the total locally generated income before it slid to 37 percent in 1998 and eventually hit rock bottom in 2004.

Traditionally, sandalwood has had a special place in the local culture. The wood is an inseparable part of religious rituals thanks to its soothing aroma.

In the past, Timor islanders would hold traditional ceremonies in which they prayed for the wood to grow and smell ever sweeter. For many of the older generation, the aroma symbolized the harmonious relations between man and his Creator and therefore it was people’s religious obligation to maintain its sustainability.

Smells great: Sandalwood is one of the major ingredients for perfumes. (Courtesy of Pixabay)

Smells great: Sandalwood is one of the major ingredients for perfumes. (Courtesy of Pixabay)

“The odiferous aroma is believed to have the power to thwart evil and fertilize the land,” says anthropologist Gregorious Neonbasu. In the days of yore, sandalwood’s metaphor was a beautiful girl who sowed fragrance for the family, the community and the land.

Mythology had it that anyone doing harm to the sacred tree was destined for misfortune, calamity and even death.

Replanting

Dumbstruck by the rapid loss of the revered plant, the local administration has been struggling to restore its past glory as producer of the world’s best-quality sandalwood.

Official statistics show the plants have been disappearing at a worrisome rate. In Timor and Rote islands, for instance, the number of sandalwood trees had fallen from 250,940 in 1998 to 38,480 in 2010. Within that 12-year span, the plant’s population plummeted by 85 percent – the fastest in any period.

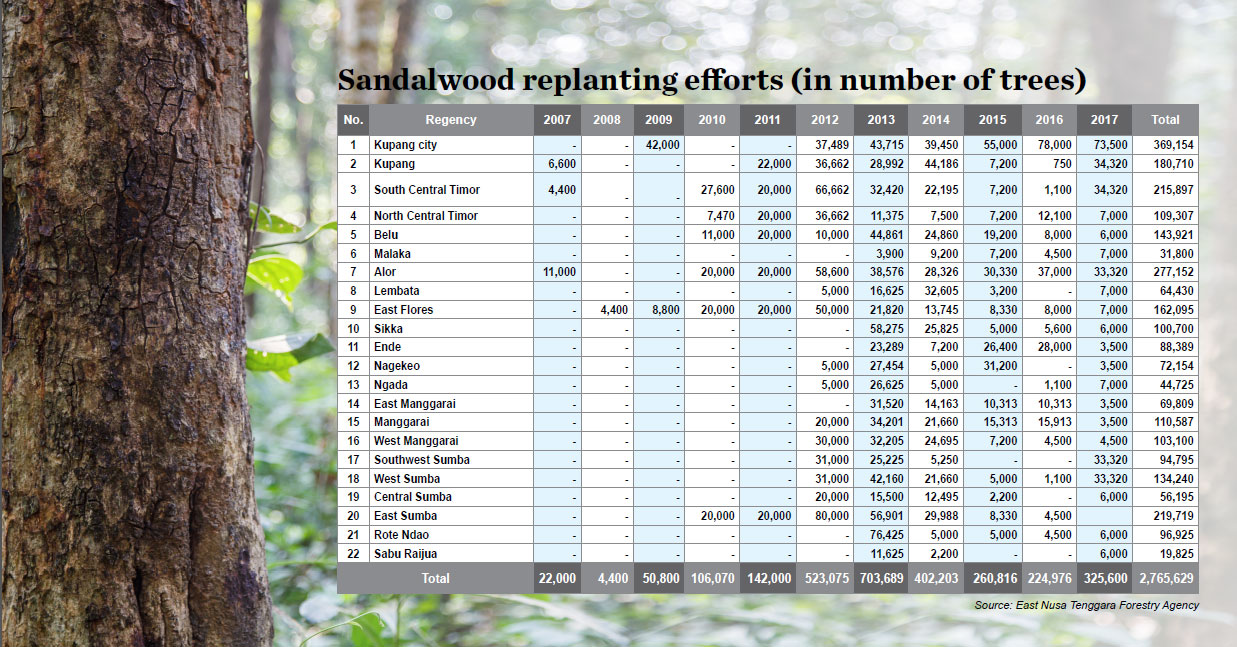

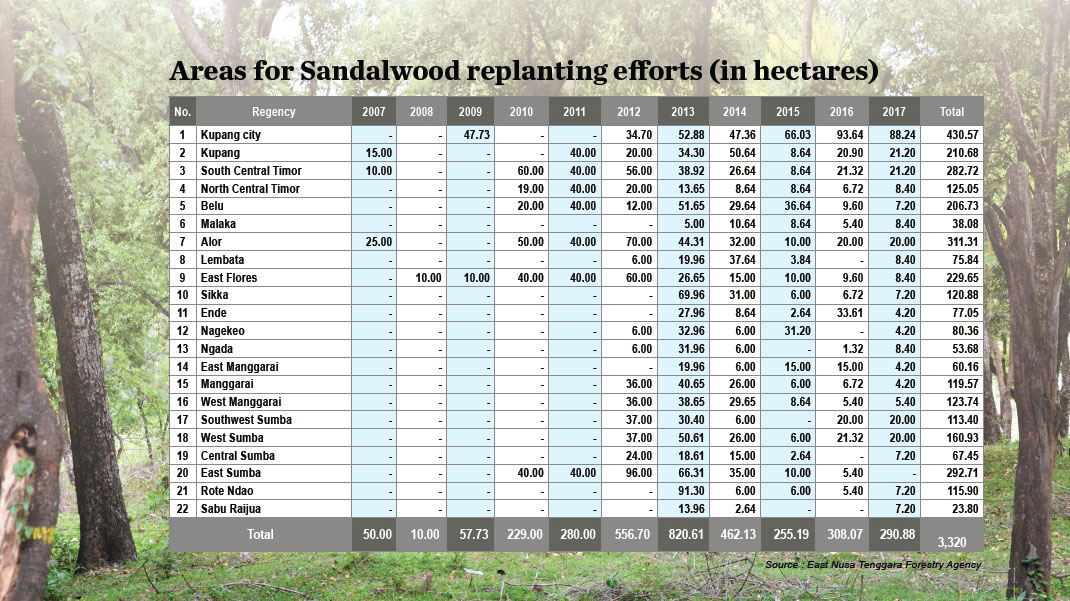

Of the numerous governors in charge since the 1960s, incumbent Frans Lebu Raya, whose second and last term will end next year, is the one who has demonstrated most concern about the imminent extinction of the iconic species. He began a replanting drive back in 2008 and in 2012, he embarked on a full-fledged campaign aimed at recreating NTT as the “sandalwood province”. He rescinded the disastrous 1986 ordinance and reestablished the people’s right to own sandalwood. Since then, his administration has spent Rp 7 billion a year on the program.

The campaign is aimed at bringing back the province’s status as Indonesia’s main producer of sandalwood. It is projected that in the coming two decades, the commodity will become a backbone of the local economy again – although this target may just be too optimistic.

Jehalu Andereas, chief of the provincial forestry office, reckons that in the 20 to 25 years to come, the sandalwood trees that have recently been planted will enter maturity and could fetch up to Rp 9 million apiece and a staggering Rp 100 million for a 50-year-old or older tree.

He says the replanting program is worth pursuing. First, NTT with its harsh topography and typically prolonged droughts provides sandalwood with the most suitable climate. The high-quality products have the most competitive edge. Second, without the conservation effort, the species would become extinct pretty soon. Third, the plants will be a long-term investment for locals.

The provincial government buys most of the much-needed seeds from local farmers for up to Rp 700,000 per kg. From nurseries, seedlings are distributed to residents through their associations called the Family Sandalwood Movement and Sandalwood Forest Movement. At schools, each student is entitled to two seedlings and the government helps them with the maintenance for the first five years of the plants’ lives.

Obviously, the ambitious program will meet formidable challenges.

Seeds are provided by the government free of charge but the fast-dwindling number of trees also means that there are not enough seeds for everybody. Recently, it has bought more seedlings from Sulawesi and Gunungkidul, Yogyakarta, which have a similar climate and topography to that of NTT, to make up the shortfall.

Furthermore, until several years ago, locals had only seen trees that grew naturally and little was known about how to cultivate them. The best-quality wood is achieved at the age of at least 45 years. It grows best in areas with low rainfall.

Despite all the convenience the local government offers, not everyone is interested in participating in the replanting program. Although farmers have now regained 100 percent ownership of the asset, many are still too traumatized by the enforcement of the draconian 1986 bylaw. Besides, the slash-and-burn farming practices remain unchecked, making replanting in the forests practically impossible. With the demise of the sandalwood industry in 2004, many farming instructors have retired and the government is desperate to find their replacements today.

But in spite of the challenges, the local government remains confident the program will succeed in restoring the territory’s past glory as the world-renowned land of sandalwood. The local forestry office claims that 2.3 million seedlings have been planted since the campaign kicked off in 2012. That accounts for 70 percent of the 3.2 million young plants the province aims to cultivate by the end of 2018.

When Governor Frans leaves office next year, he will see sandalwood budding once more throughout the sprawling islands, although he will not be able to benefit from it politically.

In the land of vanishing

sandalwood, planting for the future

That’s the tree: Rony Lie (right), a resident from Timor Tengah Selatan regency, shows his sandalwood plantation to an official. The 2-hectare area has been planted with 1,500 trees. (JP/Djemi Amnifu)

That’s the tree: Rony Lie (right), a resident from Timor Tengah Selatan regency, shows his sandalwood plantation to an official. The 2-hectare area has been planted with 1,500 trees. (JP/Djemi Amnifu)

People look in awe at Rony Lie for taking time off as a busy mechanic at an automobile repair shop to take good care of the 1,500 sandalwood plants he cultivates in his 2-hectare estate in the barren South Timor Tengah regency.

Aged between 5 and 15 years, the trees have captivated ordinary people and the government alike. The admiration stems from not only the plants’ great number but, more importantly, from the secret of his success in cultivating the species. For centuries, local people had only known sandalwood that grows wild in the forests or in their property from seeds contained in bird droppings.

People in the area began to seriously learn about sandalwood cultivation over the past decade or so after the Santalum album species became endangered because of unchecked exploitation exacerbated by poor regulation.

Rony, 56, began turning his concern into action in 2009. Then, he bought sandalwood seeds for Rp 200,000 (US$15) per kilogram from farmers at a local traditional market. Since then, he has dedicated at least one day a week to his sandalwood estate.

“I do this farming not only for profit but also for the environment. It’s also a long-term investment for my offspring,” he says. “I certainly won’t have the chance to reap the crops unless God grants me longevity.”

Rony was not joking. A sandalwood seedling takes at least 25 years to become mature and attain economic value. Truly good-quality products come from wood older than 45 years.

Treasure: A buyer (left) bargains for souvenirs made of sandalwood - a fan and a rosary – from a local craftsman in Kelapa Lima district, East Nusa Tenggara. The souvenirs are left over from sandalwood trees that have disappeared from the region. (JP/Djemi Amnifu)

Treasure: A buyer (left) bargains for souvenirs made of sandalwood - a fan and a rosary – from a local craftsman in Kelapa Lima district, East Nusa Tenggara. The souvenirs are left over from sandalwood trees that have disappeared from the region. (JP/Djemi Amnifu)

He might not be an environmental activist but conservancy was on his mind when he began to realize how serious the sandalwood extinction issue had become. He has set himself an ambitious target of helping to restore East Nusa Tenggara’s (NTT) lost glory as producer of the world’s best sandalwood – a cause that NTT Governor Frans Lebu Raya has been vigorously waging.

Rony is a self-taught sandalwood conservationist. He learned hard lessons at the start. Of the 500 saplings he planted, all but three perished. “Then I didn’t know any tricks. I began to learn that sandalwood is a unique plant and it takes good techniques to cultivate it.”

Not only is sandalwood slow-growing, but also extremely prone to diseases in its first years. It is generally understood that the first five years are the most critical in the plant’s lifetime. Growing the plant is tricky because the survival rate is only about 20 percent. It grows best on rocky land at an altitude of 600-900 meters above sea level with 600-2,000 millimeters of annual rainfall, but with short dry seasons of about three months a year.

In Rony’s case, most of his plants died after they were blighted by pests and many of the remaining few ended up being devoured by roaming cattle. In the province, cattle are traditionally let loose and this poses a major problem in the sandalwood replanting effort.

However, the frustrating first experience did not discourage him. In 2012, he launched his second attempt with 1,000 seedlings and half of them began to germinate. The 1,500-or-so trees on his farm today are the survivors of the 5,000 seedlings he has planted.

From experience, Rony has learned that sandalwood needs a good drainage system and enough exposure to the sun.

He would not reveal what he has spent on his project but it is substantial. In the harsh land where prolonged droughts are notorious, water accounts for most of his budget, especially during the dry season when his young plants need watering three times a week.

At present, he is yet to decide whether he will commercialize his estate to recoup the money he has heavily invested.

A sandalwood tree. (Courtesy of Pixabay)

A sandalwood tree. (Courtesy of Pixabay)

Business aspects aside, his toil has already paid off. The local forestry office has made him a conservation role model to inspire many. People who come to the regency with a mission of learning about sandalwood cultivation are recommended to visit his farm, which the local government has designated as a demonstration plot.

“We take people who are interested in learning about sandalwood to this site [Rony’s farm] because the government is yet to have one,” says Roby Selan, a senior official of the regency’s forestry office.

Even though people have regained their right to full ownership of sandalwood on their property as affirmed by the 2012 ordinance, few are aware of it. That explains why villagers remain reluctant to plant sandalwood.

“People are still traumatized about the bitter past,” Roby says referring to the times when the state claimed every single sandalwood plant in the province and prosecuted anyone harvesting it without official consent.

“The trauma won’t go away despite the government’s information campaign. Many still regard sandalwood as a bringer of bad luck.”

It is a long way to go back to the future when the province once again prospers from the fragrance of sandalwood.

Hard work: A craftsman finishes his work made from sandalwood and batik. The product has been exported to Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei Darussalam.(JP/Ganug Nugroho Adi)

Hard work: A craftsman finishes his work made from sandalwood and batik. The product has been exported to Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei Darussalam.(JP/Ganug Nugroho Adi)

| Producer | : | Ika Krismantari |

| Writer | : | Djemi Amnifu |

| Senior Managing Editor | : | Kornelius Purba |

| Managing Editors | : | Primastuti Handayani, Rendi A. Witular, M. Taufiqurrahman, Damar Harsanto |

| Desk Editors | : | Pandaya, Imanuddin Razak |

| Art & Graphic Design Head | : | Budhi Button |

| Photographers | : | Djemi Amnifu, Ganug Nugroho Adi |

| Technology | : | Muhamad Zarkasih, Ega Agung Nugraha, Mustopa |

| Multimedia | : | Bayu Widhiatmoko, Ahmad Zamzami, Rian Irawan |