Indonesia, whose social security system is still in its infancy 72 years after independence, has begun to adopt the Japanese insurance business model. Last month, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) invited Indonesian officials and journalists to workshops about the Japanese system. The Jakarta Post’s Pandaya, who joined the trip to Japan, shares an overview of the plan.

After three years of fully fledged operations, the social security system continues to struggle with low participant acquisition and poor premium compliance.

Both the Workers’ Social Security Provider (BPJS Ketenagakerjaan) and the Social Health Insurance Provider (BPJS Kesehatan) still have a hard time reaching people, especially those in the outer islands and far-flung areas because of limited human and financial resources.

BPJS Kesehatan official figures show that only 182 million of the roughly 255 million citizens had participated in the health insurance scheme as of Oct. 1; while 70 million were yet to be covered. Last month, it projected that its deficit would reach a whopping Rp 9 trillion (US$673.75 million) by the end of the year. President Joko Widodo aims to achieve universal coverage by the end of 2019 before his first term ends.

Still, it is faring better than the BPJS Ketenagakerjaan when it comes to acquisition of participants. So far this year, the workers’ social security provider has covered only 24 million people, or 20 percent of its target of 118 million citizens.

Carded: A man holds up his Healthcare and Social Security Agency (BPJS Kesehatan) card in Cipayung, East Jakarta. (JP/P.J.Leo)

Carded: A man holds up his Healthcare and Social Security Agency (BPJS Kesehatan) card in Cipayung, East Jakarta. (JP/P.J.Leo)

These classic problems are reminiscent of those that plagued Japan in 1961 when, ironically, it achieved its universal health insurance coverage. Eight years later, the Land of the Rising Sun managed to develop a business model to not only maintain universal coverage but also, enviously, to jack up the premium collectability rate to almost 100 percent.

Today, Japan’s social security system is among the most efficient in the world with the lowest per capita healthcare costs among the wealthiest countries. Its population is the healthiest with a life expectancy of 83 years, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), thanks largely to healthy diet and the widespread availability of high-quality health care.

Impressed by this success story, Indonesia wants to adopt Japan’s community-based business model, which relies on two entities, jimukumiai and sharoushi, which underpin the participation acquisition and the highly efficient administration.

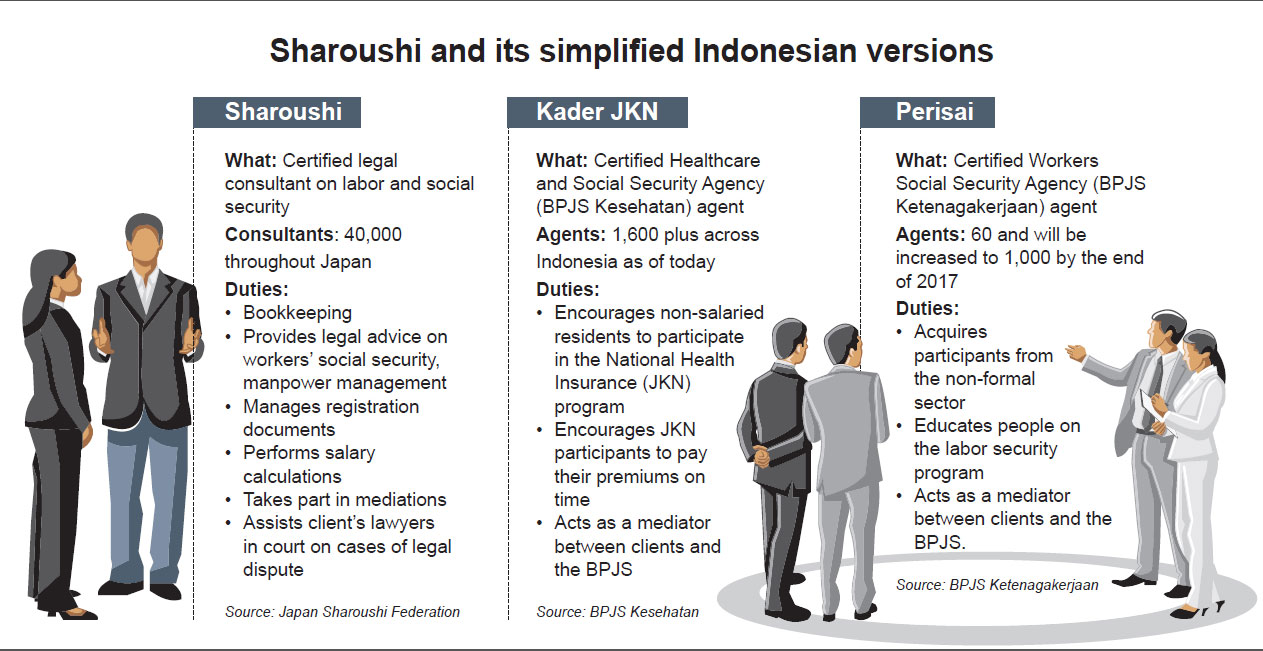

In Japan, jimukumiai refers to about 10,000 organizations, either legal or non-legal so long as they have internal statutes, which serve as the premium-collection and participant-registration machine, while sharoushi are the estimated 40,000 certified consultants who help jimukumiai acquire participants, provide clients with legal consultation and help collect premiums. There are two types of sharoushi: Those that operate as independent agents and those that are employed by companies, also known as corporate sharoushi.

Enlightenment center: Employees of the Japan Sharoushi Federation Headquarters, Tokyo, say that one of their toughest jobs is to deal with restless retiring people who call and ask questions about their pension benefits. (JP/Pandaya)

Enlightenment center: Employees of the Japan Sharoushi Federation Headquarters, Tokyo, say that one of their toughest jobs is to deal with restless retiring people who call and ask questions about their pension benefits. (JP/Pandaya)

Why ‘sharoushi’ and ‘jimukumiai’ fit the bill

BPJS officials say that the state of social security in Indonesia today is comparable to that of Japan between 1961 and 1969, in the early years after all Japanese citizens had received healthcare benefits and financial protection from the state.

It’s plain to see that Indonesia is enamored of the Japanese concept. In 2015 it began pilot projects in West Java, Aceh, North Sumatra, Yogyakarta and East Java. Since then, locals – officials and villagers alike – have stopped worrying about tongue-twisting Japanese words. So jimukumiai was Indonesianized as “social security communication center” (or SKJS) and sharoushi as “social security consultant” (KJS).

The BPJS formally adopted the Japanese system nationwide in April. As professionals, they will be certified by the BPJS Ketenagakerjaan, Manpower Ministry and the Professional Certification Agency.

Pay up: A man pays for his national health insurance premium at a minimarket in Duren Tiga, South Jakarta. (JP/Dhoni Setiawan)

Pay up: A man pays for his national health insurance premium at a minimarket in Duren Tiga, South Jakarta. (JP/Dhoni Setiawan)

Along the way to the full-fledged adoption project, the BPJS is receiving assistance from the Japanese Sharoushi Federation and the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). At home, the project receives full support from the Manpower Ministry, Finance Ministry, Health Ministry, National Development Planning Agency (Bappenas), Professional Certification Agency and the National Social Security Council.

But while BPJS leaders and their Japanese mentors are busy finalizing the scheme, they plan to give the consultants an Indonesian spin. Unlike sharoushi, the Indonesian version of consultants will be equipped with knowledge and expertise on both health and labor issues so that they will serve both BPJS Kesehatan and BPJS Ketenagakerjaan at the same time. Many Indonesian officials, however, are skeptical about this amalgamation of jobs given the distinct characteristics of BPJS Kesehatan and BPJS Ketenagakerjaan.

Until then, villagers trained as BPJS Kesehatan consultants are called Kader JKN and BPJS Ketenagakerjaan called Perisai (short for Indonesian social security movers). Local terminology absorbed from the Japanese concept has yet to be standardized.

Get going: A worker is seen busy at Mitomi Manufacturing Industry, an automotive part factory in Osaka. (JP/Pandaya)

Get going: A worker is seen busy at Mitomi Manufacturing Industry, an automotive part factory in Osaka. (JP/Pandaya)

Like Japan, Indonesia is an archipelagic country with so many islands that participant acquisition and premium collection pose a gigantic challenge. But in the future, participants living in isolated areas with no access to BPJS branch offices or the banking system will have consultants that will help them settle their premium payments.

Under the Japanese-style agency system, the freelance consultants will make money based on the number of clients they acquire so the government will not be burdened by their payrolls. When the system is adopted in Indonesia, the BPJS will save a lot of money that otherwise it would have to spend in recruiting new employees.

With the partnership concept, the contribution-collection system will be made even easier with the manifold existing local organizations such as cooperatives, banks, chambers of commerce and industry, religious organizations and customary institutions functioning as social security communication centers (the local version of jimukumiai) that collect the money and transfer it to the government. They will have authorization and training from the BPJS and the Manpower Ministry. At present, BPJS still count formal institutions like banks and post offices as well as selected convenience stores which have widespread outlets to collect premiums.

“The SKJS and KJS will take a more personal approach, targeting all community spectrums across Indonesia,” BPJS Ketenagakerjaan president director Agus Susanto said at the launch event of the Yogyakarta pilot project last year.

How far is BPJS going?

Going online: A woman tries out the Healthcare and Social Security Agency’s (BPJS Kesehatan) mobile application during a visit to a BPJS Kesehatan office in Malang, East Java.(JP/Aman Rochman)

Going online: A woman tries out the Healthcare and Social Security Agency’s (BPJS Kesehatan) mobile application during a visit to a BPJS Kesehatan office in Malang, East Java.(JP/Aman Rochman)

Happy with the pilot project outcomes, both the BPJS Ketenagakerjaan and BPJS Kesehatan will go full throttle with the adoption of the Japanese concept next year. The providers intend to have 4,000 agents.

“We will selectively adopt the Japanese system taking into account our labor, legal, and socio-economic conditions,” says Ahmad Sulintang, chief of BPJS Ketenagakerjaan’s change management office. A stark difference is that as an advanced country Japan has reliable information technology that makes any areas accessible.

In the first years, Perisai agents will focus on salaried workers in micro- and small-scale enterprises as well as self-employed people, while medium and large-scale industry workers will be approached by BPJS Ketenagakerjaan marketing officers.

In the long run, self-employed, or non-salaried people, who account for 71 million of Indonesia’s 122 million workers, are expected to have access to the social security scheme.

The BPJS Ketenagakerjaan is currently drafting standard operating procedures for Perisai agents, calculating incentives for their service and the information system that will support their jobs. The agents will be provided with mobile applications in order to boost participation.

Pitfalls

Hard at work: Workers at Mitomi Manufacturing Industry, an automotive part factory in Osaka, in their workshop. In the Japanese cost-sharing system, employers shoulder 70 percent of medical costs and the remaining 30 percent is paid by the employees.(JP/Pandaya)

Hard at work: Workers at Mitomi Manufacturing Industry, an automotive part factory in Osaka, in their workshop. In the Japanese cost-sharing system, employers shoulder 70 percent of medical costs and the remaining 30 percent is paid by the employees.(JP/Pandaya)

The establishment of social security communication centers and recruitment of independent agents throughout the 34 provinces will, no doubt, create thousands of new jobs. In Japan, any jimukumiai that can collect 100 percent of the premiums is entitled to 2 percent as kickback in addition to the standard commissions.

However, competency-wise, the BPJS is likely set the bar much lower for Perisai and Kader JKN than Japan does for its sharoushi candidates.

In Japan, sharoushi is a serious profession. Candidates have to command skills and proficiency proven through hard tests on social security, legal and labor subjects. According to Yoshihiko Ono, chairman of the Osaka Sharoushi Association, the average pass rate was only 2.5. Last year, for example, 66,000 tried their luck but only 1,700 passed the tests.

In Indonesia, Perisai and Kader JKN will have the qualifications of a regular insurance agent whose main job is acquiring new participants and persuading clients to pay their premiums on time. At this stage, the tests that candidates take are a lot easier than those taken by college graduates seeking legal consultant status. This year’s recruitment tests were taken by 4,750 applicants and 2,630 were admitted – a remarkable pass rate of more than 50 percent.

Indonesia is pinning high hopes on a successful social security system. Its lofty dream is to obtain universal health coverage in two years and develop a system of its own that is hopefully better than that of Japan, its mentor.

For BPJS agents, dedication comes first

Hailing from villages far from the hustle and bustle of urban centers, Warsinah and Supiyah never fancied a job in insurance. Now in their 40s and living in Bekasi, a vibrant industrial city just east of Jakarta, they have been fast learning the ABCs of the insurance industry.

When the Social Health Insurance (BPJS Kesehatan) and the Workers Social Security (BPJS Ketenagakerjaan) schemes formally adopted the Japanese social security business model in April, the women successfully applied for positions as BPJS Kesehatan agents. They are fond of sharing their experience in the early days, as they made their door-to-door visits to introduce themselves and their mission in their respective districts. Some of the residents surprised them, welcoming them with open arms, while others treated them with suspicion. Warsinah, who comes from South Sumatra, and Supiyah from Central Java, love to recall how they were humiliated when they were turned away by some residents who thought they were frauds.

“Some people thought I was a debt collector or a con artist,” Warsinah says.

Menial: Warsinah, a BPJS Kesehatan agent (Kader JKN) in Bekasi, West java. Like many other agents, she takes up the job for additional income.(JP/Pandaya)

Menial: Warsinah, a BPJS Kesehatan agent (Kader JKN) in Bekasi, West java. Like many other agents, she takes up the job for additional income.(JP/Pandaya)

All that happened about six months ago. Today, thanks to their perseverance, Warsinah has 250 families under her management and Supiyah, 220 families. As they had earned the people’s trust, many now seek them out for help with their BPJS health insurance, from registering to settling premiums. The two are well versed in the agency’s administrative procedures and are mobile-app savvy.

Agents like Warsinah and Supiyah focus on member acquisition and premium collection. Women represent most of the 1,600 BPJS Kesehatan agents throughout the archipelago. They are preferred because they are generally perceived to be more “gung-ho” than men and have better interpersonal skills. Throughout Bekasi regency, only eight of the 25 JKN agents are men.

Unlike sharōshi, “labor and industry attorneys” of the Japanese social security system that Indonesia has adopted, JKN agents focus on non-salaried members. This segment comprises the highest uncollected premiums for various reasons, like inadequate incomes, lack of banking access and lack of knowledge, particularly on the consequences of being uninsured.

Formal employees typically have the premium payments deducted from their salaries, so this segment’s premium collection rate nears 100 percent.

Each JKN agent is tasked with overseeing a maximum 500 families in their subdistrict. Once they achieve their target of participating families, they earn a monthly commission of about Rp 3 million (US$230) – a meager income they understandably fret over. That is why housewives join the agency as a side job. Warsinah’s primary occupation, for example, is as a shopkeeper.

Officials at BPJS Kesehatan Bekasi have reported a surge in the premium collection rate in the past five months thanks to its agents. According to Nur Indah Yuliaty, manager of BPJS Kesehatan Cikarang, the branch office has seen its collection rate increase from 50 percent to 55 percent.

To qualify as a BPJS agent, a candidate needs to have Rp 20 million as starting capital and be a bank agent or work under a bank agent so they are eligible for loans from banks or other financial institutions.

Together in health: Residents line up at a clinic in Malang, East Java, where residents can pay their national health insurance premiums with dry waste.(JP/Aman Rochman)

Together in health: Residents line up at a clinic in Malang, East Java, where residents can pay their national health insurance premiums with dry waste.(JP/Aman Rochman)

During a recent visit to meet with JKN agents in Bekasi, Agus Mustopa, BPJS Kesehatan’s deputy director of contributions, acknowledged that the agents’ income was far from adequate, but assured that the government was doing everything it could to improve the commission system.

BPJS is aware that the agents’ meager income needs urgent attention. It needs dedicated agents to achieve the Joko Widodo administration’s universal health coverage target by 2019. Ideally, Agus reckoned, Indonesia would need 10,000 JKN agents to deal with the arrears generated by an estimated 10 million members. BPJS Kesehatan is currently supported by 1,600 agents across the country.

“People’s participation is badly needed to make the national health and social security a success,” says BPJS Kesehatan president director Fachmi Idris. “Recruiting JKN agents is also an effort to empower civil society.”

Warsinah and Supiyah cannot wait until the BPJS’s promise of a better commission and system are fulfilled, so that they can dedicate themselves as full-time JKN agents. Until then, Warsinah will continue to double as a shopkeeper while Supiyah will attend to her household chores. (JP/pan)

Checkup: A medical staff and an agent from Social Health Insurance Provider (BPJS) check medical equipment in a hospital in Gorontalo.(Antara/Adiwinata Solihin)

Checkup: A medical staff and an agent from Social Health Insurance Provider (BPJS) check medical equipment in a hospital in Gorontalo.(Antara/Adiwinata Solihin)

| Producer | : | Ika Krismantari |

| Writer | : | Pandaya |

| Senior Managing Editor | : | Kornelius Purba |

| Managing Editors | : | Primastuti Handayani, Rendi A. Witular, M. Taufiqurrahman, Damar Harsanto |

| Desk Editors | : | Pandaya, Imanuddin Razak |

| Art & Graphic Design Head | : | Budhi Button |

| Photographers | : | Pandaya, Aman Rochman, Dhoni Setiawan, P.J. Leo |

| Technology | : | Muhamad Zarkasih, Ega Agung Nugraha, Mustopa |