The recent bust of a prostitution service disguised as an online dating platform has put the controversy over nikah siri (informal unregistered marriage) back into the spotlight. The Jakarta Post’s Corry Elyda and Ika Krismantari discuss why people still love to embrace this bald-faced hypocrisy.

Imagine arriving at a wedding ceremony, but you find no fancy dresses, no stunning decorations, no crowd and no Instagram updates. Around you are the bride, bridegroom, cleric and a couple of perfect strangers. What reigns is a sense of secrecy.

Such a scenario can be very real here in Indonesia when a couple has their nikah siri blessed. Secret lovers may opt for a simple wedding ritual on the belief that all they need for the union of a man and a woman is love, if not lust, and the divine blessing.

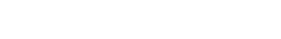

Under Islamic law, a man can marry a woman as long as there is a guardian for the bride — usually her father or a male relative — as well as witnesses and a dowry. This practice of nikah siri (literally translates as secret wedding) remains commonplace in the predominantly Muslim country. In Arabic, sirri means “clandestine.”

From the Islamic religious perspective, nikah siri is valid, but not under Indonesia’s secular laws. Law No. 1/1974 on marriage stipulates that a marriage is deemed legitimate if it fulfills religious formalities and is registered by the state. Nikah siri lacks the latter prerequisite and such a wedding is usually performed by a penghulu (a Muslim cleric), who is not authorized by the Religious Affairs Ministry.

Paper matters: Some couples conduct nikah siri because of financial reasons, as formal weddings are too costly and involve complicated registration processes. (Shutterstock)

Paper matters: Some couples conduct nikah siri because of financial reasons, as formal weddings are too costly and involve complicated registration processes. (Shutterstock)

Because nikah siri is mostly kept as a secret and is not registered, it is next to impossible to measure its prevalence. In 2012, the Empowerment of Female Heads of Households Program (Pekka), an NGO assisting widows in conflict regions, conducted a study in 111 villages across 17 provinces, and concluded that at least 25 percent of the population was in unregistered marriages.

Although the marriage is religiously valid, this argument does not end its controversy. Critics say that nikah siri is adultery hidden behind the mask of religion. These couples — who often include well-known celebrities and politicians — are subject to ridicule, prejudice and even alienation.

But the sheer prevalence and the general perception of the practice reveal an inconsistency that amounts to hypocrisy.

Stamp of secrecy: A stamp bearing the logo of matchmaking website nikahsirri.com is on display as case evidence. The website is suspected of being a front for a prostitution service. (Antara/Sigid Kurniawan)

Stamp of secrecy: A stamp bearing the logo of matchmaking website nikahsirri.com is on display as case evidence. The website is suspected of being a front for a prostitution service. (Antara/Sigid Kurniawan)

The recent ban on nikahsirri.com, a website offering matchmaking and secret wedding services, and the arrest of its owner, Aris Wahyudi, may well reflect the attitude. Police have accused him of offering nikah siri services with virgin boys and girls for money. In fact, nikahsirri.com is not the only website of its kind in existence, but the long hand of the law has yet been able to claw out the others.

Recently, The Jakarta Post visited an agent in Tebet, South Jakarta. Tucked in a residential area, the unpretentious office stands out for its signboard carrying the business owner’s single name squeezed among his academic and clerical titles: Prof. Dr. KH. Aulia MA.

The man was nowhere to be seen. In charge that day was his son, Nurul Huda, who usually takes the role of assistant and witness.

“My father can wed the couple as well as become the guardian for the bride,” said Nurul. He visibly withdrew upon realizing his guests were journalists.

For the service, the agent sets fees ranging from Rp 2 million (US$148) for couples who bring their own witnesses and guardian, to Rp 3 million if these must be provided.

Nurul said his father usually administered at least one nikah siri a week. His clients vary, ranging from men who wish to take a second wife without the approval of his first wife, young and underaged couples, to divorcees.

Nurul and his father offer the services online and offline publicly. Just google “nikah siri in Jakarta” and their names will appear at the first click.

Where is the law?

The ambivalent attitudes surrounding nikah siri in Indonesia partly stem from legislation. Generally, people know its legal and social consequences. For instance, the wife and child are not entitled to an inheritance or state documents. Although the 1974 Law on marriage makes it illegal, it does not explicitly ban or criminalize nikah siri.

In a rare case, a housewife in Lumajang, East Java, filed a lawsuit against her husband in 2010 for marrying another woman without her consent. The 1974 Law stipulates that men cannot take a new wife without consent from his legal wife (or wives), or he faces criminal charges that carry a maximum jail term of five years.

Two books, one love: The government issues two separate marriage books for the husband (left) and the wife when a couple holds an Islamic wedding. (Antara/Irwansyah Putra)

Two books, one love: The government issues two separate marriage books for the husband (left) and the wife when a couple holds an Islamic wedding. (Antara/Irwansyah Putra)

A Muslim may have up to four registered wives, but in practice, the formal procedures have been made so complicated that, theoretically, it is next to impossible.

The situation became even more complex after the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) issued a fatwa (edict) in 2006 making nikah siri halal (permissible under Islamic law), as long as it fulfills the sharia requirements: witnesses, dowry and guardians.

That is why even though nikah siri is generally criticized, it is widely practiced. People have various reasons to opt for this marriage model. Some parents would let their underage daughters marry this way and legalize the nuptials later when the women have reached adulthood. Others do it on the pretext that nikah siri would free them from the guilt of adultery.

Arina Rohmatul Hidayah, 23-year-old mother of one, chose nikah siri as a 20-year old student in Yogyakarta because she wanted people to believe her boyfriend was her legitimate husband. Her tactic worked. People stopped gossiping about her relationship and she could better focus on her study, and then formalized her union after graduation.

Tholha, a Religious Affairs Office (KUA) officer in Surabaya, said many men prefer to have a nikah siri with their next wife because the official procedure is just too complicated and inefficient. The 1974 Law on marriage requires men who want to have a second wife to get the approval from their first wife and convince the state that they can guarantee the well-being of both families.

“Without these documents, a man can not take a second wife,” Tholha said.

Lifetime commitment: A groom (right) shakes the hand of an officiant during an Islamic wedding ceremony. (Shutterstock)

Lifetime commitment: A groom (right) shakes the hand of an officiant during an Islamic wedding ceremony. (Shutterstock)

While some men use nikah siri to justify adultery, others take it to the next level and use it to justify prostitution, which is illegal by both the religious and secular laws of Indonesia. The case of nikahsirri.com is an example of how nikah siri practices can be manipulated for prostitution.

Another form of disguised prostitution is the contractual marriage. Puncak in West Java, a popular hilly resort about 70 kilometers south of Jakarta, is widely known for catering to these “sin-free” short unions. Here, Middle East men are the chief patrons.

“They secretly perform nikah siri in hotel rooms [...]. Middlemen acting as agents also serve as witnesses and guardians for their clients’ convinience,” said 54-year-old Puncak resident Dadeng Hidayat.

Marginalized: Nikah siri does not benefit women, as the practice does not acknowledge a wife’s rights in the marriage. (Shutterstock)

Marginalized: Nikah siri does not benefit women, as the practice does not acknowledge a wife’s rights in the marriage. (Shutterstock)

Victimizing women

For many years, rights activists have been campaigning against nikah siri, which they say victimizes women.

Maria Ulfah Anshor, a seasoned Muslim-feminist activist, said nikah siri disadvantages women because it denies them and their children civil rights, like the vital birth certificate and an inheritance from their siri husbands.

“In Islam, the fundamental goal of marriage is to build a family. Because the informal bond is already disadvantageous to women, on what ground can we possibly believe that religion allows it?” she argued.

In her view, nikah siri also contradicts the Sunnah (teachings of the Prophet Muhammad), who strongly urges the faithful to make public their marriage to prevent libel.

If you think that men are the ones who always initiate siri, think again. Many women want it too because they cling to the belief that nikah siri is also an official part of a Muslim’s religious duties, according to clinical psychologist Kasandra Putranto.

Criticism also comes from the National Commission on Violence Against Women (Komnas Perempuan), which sees the practice as a grave danger for women.

All you need is love: Nikah siri weddings are unregistered and undocumented, and such unions are acknowledged only under Islam. They are often conducted in secrecy and are attended only by close family and friends. (Shutterstock)

All you need is love: Nikah siri weddings are unregistered and undocumented, and such unions are acknowledged only under Islam. They are often conducted in secrecy and are attended only by close family and friends. (Shutterstock)

In its latest annual report, Komnas Perempuan attributes people’s repudiation to make their unofficial marriage public to rampant cases of domestic violence. For example, in North Kalimantan, a mother placed her baby in a fridge out of shame that the child was born out of an illegitimate relationship. Last week, a Southeast Sulawesi politician was allegedly murdered by his third siri wife over a domestic tiff.

It looks as if nikah siri will remain a perplexing issue in Indonesia. After hanging in the balance for almost a decade, the 1974 Law on marriage will be amended by House of Representatives lawmakers, but this time around, tightening the legal age for marriage would likely be a more appealing issue.

In Puncak, thin line between true love and pure lust

Upon catching a glimpse of a couple holding their little son’s hands, ambling beside a busy highway in Puncak on a misty afternoon, Dadeng Hidayat, a local villager, immediately noticed them. They are an interracial couple; the man is tall with physical features of a Caucasian and Asian mix and the boy has his father’s beautiful round eyes.

“The man is a refugee,” the 54-year-old Dadeng said. “Many immigrants marry local women here.”

In this cool resort area, interracial couples like this one are all too familiar a sight. Many of them mill about in certain shops and restaurants catering mainly to Middle Eastern, especially Saudi Arabian, visitors. The establishments are designed to look and feel Arabic -- the architecture, character and interior. Arab cuisines are widely available.

Among flowers: Saudi Arabian tourists visit a flower garden in Puncak, West Java. Indonesia welcomed around 186,000 tourists from Saudi Arabia in 2016 and Puncak is one of their favorite destinations. (Kompas/Raditya Helabumi)

Among flowers: Saudi Arabian tourists visit a flower garden in Puncak, West Java. Indonesia welcomed around 186,000 tourists from Saudi Arabia in 2016 and Puncak is one of their favorite destinations. (Kompas/Raditya Helabumi)

According to official statistics, Indonesia welcomed around 186,000 tourists from Saudi Arabia in 2016 and Puncak remained one of their favorite destinations.

Living up to its “Little Arab” nickname, Puncak also hosts refugee camps run by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The Coordinating Political, Legal and Security Affairs Ministry recorded 2,300 illegal immigrants in Puncak last year, 1,600 of them being accommodated in the Bogor regency.

Mostly Iraqis and Afghans, the illegal immigrants have been temporarily resettled there after they were stranded on their way to Australia. While awaiting their relocation to a third country, they enjoy the freedom of mingling with locals, and some find the love of their lives.

Because they do not have the requisite documents, the aliens cannot legally marry local women, but Islam gives them a way out: the practice of nikah siri (unregistered marriage). So prevalent is it in Puncak that over time it has lost its religious sanctity and become utter prostitution catering chiefly to Middle Eastern tourists.

Nandar Winandar, the Tugu Utara subdistrict chief of administrative affairs, acknowledges that nikah siri is common in the area with many cases involving local women and foreign men.

“Many couples’ marriage are unregistered here,” Nandar told The Jakarta Post. Their reasoning is standard -- those wanting to have another wife do not want to go through the arduous bureaucratic procedures.

Official union: A man and a woman marry in front of a judge during a mass wedding in Surabaya, East Java. (Antara/Moch Asim)

Official union: A man and a woman marry in front of a judge during a mass wedding in Surabaya, East Java. (Antara/Moch Asim)

Under the secular law, divorcees wanting to remarry need legal court documents, which for most people are just too costly and time consuming to obtain. So why not go the religious, Islamic way that allows husbands to divorce their wives simply by writing a statement sealed with a stamp and proclaiming the separation in front of witnesses?

“In the past, people could tamper with their ID cards to change their marital status. [But] now it is impossible to do with electronic ID cards,” he said. Moreover, he added, documents for a single divorce may cost up to Rp 4 million (US$296).

The presence of illegal immigrants makes nikah siri an even bigger business. Yusuf Sukyani, an assistant to a local Islamic Religious Affairs Office penghulu (Muslim cleric), said he could wed three siri (unofficial) couples a year.

“In Islam, if you fulfill the basic requirements that consist of dowry, guardians and witnesses, your marriage is valid,” the 71-year-old said.

Even though officiating a siri marriage is easy, Yusuf exercises caution for his own good. He coordinates with the bride’s neighborhood unit chief to make sure that the marriage will not create a problem in the future.

“I just don’t want the man to falsely claim he is a bachelor but then his wife comes and complains that I wed her husband without her consent,” he said.

People also opt for nikah siri if the age gap between the man and the woman is too wide, or the couples are “too old” to marry. In this case, as Yusuf said, people are too embarrassed to wed officially, let alone to throw a wedding bash.

Few local residents are probably as well-versed about “sin-free”prostitution in Puncak as Dadeng, who has been in the tourism business in Puncak for 30 years.

“Service providers usually also provide the guardians, the witnesses and the penghulu who will wed them,” he said.

The guardians and the witnesses can be anyone while the penghulu is a cleric who can speak survival Arabic. Dowry, which constitutes the payment for the the girl, is worth between Rp 8 million and Rp 10 million for a one-week stand, he said.

But some citizens in Puncak use people from outside the region as a scapegoat in their bid to defend its reputation. Officials and residents alike say that the practice which gives their homes a bad name involved mostly Middle Eastern tourists and women from other regions.

“None of the girls are locals,” Nandar said. “They come from other regions like [the neighboring] Sukabumi and Cianjur.”

The lack of serious law enforcement is also baffling. Since 2013, police have conducted multiple raids on hotels and villas they suspect allow prostitution. But, as Dadeng said, the vice remains rampant in Puncak.

In the dark: Despite the controversy surrounding the practice, nikah siri remains common in Indonesia. (Shutterstock)

In the dark: Despite the controversy surrounding the practice, nikah siri remains common in Indonesia. (Shutterstock)

| Producer | : | Ika Krismantari |

| Writers | : | Corry Elyda, Ika Krismantari |

| Senior Managing Editor | : | Kornelius Purba |

| Managing Editors | : | Primastuti Handayani, Rendi A. Witular, M. Taufiqurrahman, Damar Harsanto |

| Desk Editors | : | Pandaya, Imanuddin Razak |

| Art & Graphic Design Head | : | Budhi Button |

| Photographers | : | Sigid Kurniawan, Irwansyah Putra, Raditya Helabumi, Moch Asim |

| Technology | : | Muhamad Zarkasih, Mustopa, Ega Agung Nugraha |

| Multimedia | : | Bayu Widhiatmoko, I Gede Dharma JS, Rian Irawan, Ahmad Zamzami,

Citra Asih |

| Voice Over | : | Liza Yosephine |