Indonesia may not yet have an unmanned establishment like Jack Ma’s Tao Café in Hangzhou, China, or driverless buses like those in France and Switzerland, but the impact of digitalization on employment in the country is becoming increasingly obvious. The Jakarta Post journalist Stefani Ribka examines how the digital revolution will continue robbing people of jobs but considerably improve business efficiency at the same time.

Nengsi Atmaja, the owner of photo shop Simpati Foto at Palmerah Market in Jakarta, vividly remembers she had seven competitors in the area back in 1977. Today, only two remain with, of course, far fewer attendants. In the heyday of the 1990s, Simpati employed 10 people. Now only four remain.

“People nowadays don’t print as many photos as they used to,” she says. “Everyone can see images instantly on their smartphones and if they want, they can print them with their own printers. Unlike analog photo technology, digital printing requires only a few people.”

The state of employment at the photo studio is just a minute example of how digitalization has adversely impacted employment. Massive job losses have been seen the telecommunication, tourism and hospitality, banking, media, toll road, manufacturing, construction, services and art sectors.

While no exact figure exists on the number of jobs that have been lost as a result of automation and mechanization, latest Central Statistics Agency (BPS) data shows that working hours in the formal sector are decreasing and the number of informal jobs increasing.

The working hour index stood at 101.4 as of June, a drop from 104.95 in the same period last year and the lowest second quarter index since 2012. In the index, 100 indicates working hours of eight hours per day; the lower the index, the fewer the working hours.

Sectors with a major drop in working hours include manufacturing, retail and automotive repairs, information and communication and service firms.

In line with that, the number of informal workers increased by 2.74 million people to 72.67 million as of February from that during the same month in 2015. Informal jobs are those that are unmonitored and untaxed by the government.

“The decline in working hours could be a result of digitalization or weakening growth in the sector itself. The falling index means people work fewer hours or do less overtime so they have more time to do informal jobs, like being Uber or Go-Jek drivers,” said Samuel Aset Manajemen economist Lana Soelistianingsih.

A study by the International Labor Organization (ILO) forecasts that more than 60 percent of salaried jobs in selected labor intensive-industries in Indonesia face a high risk of automation.

Automotive and auto parts as well as electrical and electronics face a 60 percent risk, textiles, clothing and footwear 64 percent and business process outsourcing and retail as high as 85 percent, according to the 2016 report. The report also highlighted 1.7 million office clerks being at a high risk of dismissal.

While data on impacted automotive factory workers is not immediately available, automation has happened even on assembly lines, unlike in the past, when machines were only used in welding and painting, says Jongkie Sugiarto, chairman of the Association of Indonesian Automotive Manufacturers (Gaikindo).

While manufacturing is predicted to face major ramifications from automation, the service and creative industries face even more real threats.

State-owned Telekomunikasi Indonesia (Telkom) has reduced its employees to 15,000 people from 30,000 in 2007 through early pension plans and job transfers to its subsidiaries.

In the early 2000s, it launched integrated mobile apps that allow employees to electronically submit work reports and implement administrative routines faster, scrapping various manual jobs usually done by administrative officers.

The rapid development of information and technology has also created new business models, such as those adopted by online travel and hotel booking website traveloka.com and ride-hailing apps Uber and Go-Jek. The internet platforms offer low prices to gain long-term market shares — and not short-term profit — on the back of huge capital.

The highly efficient business models have indirectly cost the jobs of thousands of conventional ticketing officers and taxi drivers. The emergence of tech startups like Traveloka has indirectly caused 700 ticketing agencies to stagnate in the past three years, according to the Association of Indonesian Tour and Travel Agencies (Asita).

Asita chairman Asnawi Bahar says that with less capital, it is almost impossible for conventional agencies to compete with the mighty newcomers in terms of price. What they can do to survive is move to online and improve efficiency and service.

“Startups such as Traveloka … are burning money [to win long-term market shares] by offering very low prices. Let’s be fair; this constitutes a monopoly if they keep their prices low on the back of their vast foreign capital,” he says.

The banking sector is more digitalized than ever. Banks are pouring money into spoiling customers with a digital experience rather than establishing new brick-and-mortar branches. State lender Bank Mandiri, for example, has opened only 200 new physical branches this year, down from 600 in the past.

Automation in the back office has also cut the time that banks need for loan application assessments to only a few hours from three days in the past. Consequently, fewer administrative workers are needed.

“Banks are doing this and no one wants to be left behind in the competition,” said Mandiri senior executive vice president for human capital Sanjay Bharwani.

The number of permanent, contract and outsourced employees at Bank Mandiri dropped 1 percent to 77,250 people as of September, but Sanjay was quick to say that the bank planned to recruit new staff at year-end to maintain the number of employees at last year’s level.

The internet has also changed the way people stay up to date with current affairs, driving them away from physical newspapers to virtual platforms.

The number of national newspapers and magazines has shrunk to 98 and 120, respectively, from 101 and 132 in 2015, research firm Nielsen data shows.

Thousands of media workers were laid off during that period. Major media groups like Kompas-Gramedia and MNC are among those hardest hit.

The side effects of automation on the workforce became even more evident when state toll road operator Jasa Marga started enforcing e-toll payments at tollgates on Oct. 1, resulting in thousands of tollgate attendants for 988 tollgates being moved to positions within and outside the firm.

No more cash: Cars enters a toll gate in Slipi, West Jakarta. The use of e-money on all toll roads coutrywide has improved efficiency but has cost thousands of tollbooth attendants their jobs. (JP/Seto Wardhana)

No more cash: Cars enters a toll gate in Slipi, West Jakarta. The use of e-money on all toll roads coutrywide has improved efficiency but has cost thousands of tollbooth attendants their jobs. (JP/Seto Wardhana)

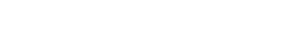

In view of the real consequences automation is having on the workforce, experts have called on the government to upgrade the education system and revise the obsolete 2003 Manpower Law. The ILO has suggested that the government equip its manpower with appropriate and in-demand skills, such as data analytics and IT competence.

For now, no significant measures have been put in place by the government. Most state elementary schools are rural SD Inpres — those designed by the authoritarian New Order regime, which fell from power in 1998 — which are usually in dire lack of basic facilities, let alone digital laboratories, Lana of Samuel Aset Manajemen has pointed out.

Almost all of 153,000 Inpres elementary schools need revitalization, but the government will be able to renovate only 60,000 of them by year-end, according to the BPS and the Education and Culture Ministry.

Failure to improve the education system will likely widen the wage gap between skilled and unskilled workers.

Less than 9 percent of the country’s 11 million workers have university degrees. Furthermore, more than 16 percent, or 20.6 million, either did not complete elementary school or have never been to school. Most, or 67 percent, come from rural areas, according to the ILO 2016 report.

To mitigate the wage gap in the digital era, economists have suggested a robot tax scheme, through which firms using robots or machines are taxed accordingly. The revenue could then be used to improve manpower quality or as an incentive for labor-intensive firms.

Revising the Manpower Law is also deemed urgent. Economist and former finance minister Chatib Basri has criticized the 2003 Manpower Law as being obsolete and not accommodative to changes arising from digitalization. The law rewards employees based on working hours instead of outcome. He said the law should also allow companies to cut their workforce if they go digital.

“The Manpower Law regulates employees’ working hours, whereas with digitalization, people can work shorter hours and get the same results. So regulations should be performance-based, rather than based on working hours,” he says.

“The law should be flexible enough to accommodate change. What we can change [more frequently] is the technical regulations.”

The Manpower Ministry is currently preparing a regulation to accommodate the fast changing world of work.

“Despite the more virtual business relations, we still need a clear regulation because it involves workers and employers,” Minister Hanif Dhakiri says.

In digital job market, millenials are spoiled for choice

While digitalization may have cost millions of jobs worldwide, it has also created practically unlimited new job opportunities for the tech savvy, especially for millennials – those born in the 1980s and 1990s. Already, this age group dominates the local workforce but few of them actually fit the bill.

The phenomenon of old jobs lost and new jobs awaiting is reminiscent of the transitional period from the 19th to the 20th century when motor vehicles replaced horse-drawn transportation, so the renowned economist Rhenald Kasali from the University of Indonesia reflects in his latest book Disruption.

Thousands of farmers, blacksmiths and carters became jobless then but new jobs arose in automotive engineering, road construction, traffic management and insurance, among others. Today, the new jobs require skills in information and technology (IT), analysis and creative thinking. Gone are the repetitive and administrative jobs that can be more efficiently done by machines.

International management consulting giant McKinsey & Co has foreseen that digitization has the potential to create 3.7 million jobs and improve workers’ productivity significantly in Indonesia between 2016 and 2025.

The World Economic Forum (WEF) forecasts new employment opportunities will arise mostly in such sectors as business and financial operations, management, computer and mathematics, architecture and engineering, sales, education and training.

Today, innumerable new jobs that people would never have heard of 10 to 20 years ago are present in various sectors from lifestyle industries to banking and manufacturing. Consider these: barista, blogger, app developer, smart control-room operator, game developer, dog whisperer, drone operator and many more.

Various firms, state lender Bank Mandiri for instance, have come up with posts like IT security, IT risk management, data scientist, enterprise data management and decision analyst. Publicly listed consumer goods giant Unilever Indonesia has specific teams to develop e-commerce potential to partner with digital entities, social media consultants and specialists.

While skills required for those jobs are getting more and more specific, employers are compelled to provide appropriate facilities and ambience to stimulate creativity and cater to various workforce generations’ characteristics, especially the millennials.

Millennials account for more than 40 percent of the Indonesian workforce, rising to 60 percent by 2020.

The Center of Reform on Economics (CORE) Indonesia executive director, Mohammad Faisal, said millennials tended to be more competitive and dynamic or likely to job-hop more than the previous generations as a result of their shaping environments. They also tend to prioritize a work - life balance over financial rewards.

“Millennials are shaped by demands for higher skills amid fast-changing IT advancement that makes them efficiency-oriented and they frown upon inflexible working hours. They also grew up in an era when information was readily accessible and transportation very easy so they’re very mobile,” he told the Post.

With such traits, companies are competing to provide the most accommodative facilities to create a conducive ambience in the digital era.

Unilever and state telecommunication firm Telekomunikasi Indonesia (Telkom) are among those most agile in adjusting themselves to digitization and accommodating millennials.

Unilever has shifted from attendance-based systems to outcome-based ones for their employees’ performance appraisal model. Workers are not obliged to come to the office and are allowed to work anytime and anywhere at their convenience.

For those who opt to work in the office, the multinational company has designed its 5-hectare headquarters in BSD City, Banten, for them, too. To create a relaxed ambience, the office has been built with a green concept. There, employees do not have fixed desks; they can work anywhere in the building and freely interact with colleagues. The head office is also equipped with a fitness gym, yoga center and daycare.

“The spatial planning inside Graha Unilever supports flexibility and agility in working as well as colleagues bonding […]. This is our new standard to support employees’ dynamics and productivity,” Nanang Chalid, Unilever head of human resources (HR), says.

Telkom, meanwhile, has created a mobile app for its employees to submit work reports, request leave, conduct performance appraisal, get payment slips and many more, for efficiency’s sake. It also operates employee buses fitted with digital devices that staff can work with and mark their attendance while commuting.

In view of the revolutionary changes that digitization brings to work, Forum Human Capital Indonesia (FHCI) director Sulung Raspati suggests that human capital management acts as a business partner for firms. Employers will have to be agile in creating new positions, seeking and maintaining the right people instead of just implementing administrative routines.

“HR needs to have profound business knowledge and vision in this sort of transition time. If a firm goes bankrupt, it could be partly blamed on HR incompetence; it’s not necessarily [the fault of] business operations,” he told The Jakarta Post.

Smart cards: Policewoman show off their electronic ID cards. High tech devices have made administrative and repetitive jobs relics of the past in modern offices. (JP/Seto Wardhana)

Smart cards: Policewoman show off their electronic ID cards. High tech devices have made administrative and repetitive jobs relics of the past in modern offices. (JP/Seto Wardhana)

| Producer | : | Pandaya |

| Writer | : | Stefani Ribka |

| Senior Managing Editor | : | Kornelius Purba |

| Managing Editors | : | Primastuti Handayani, Rendi A. Witular, M. Taufiqurrahman, Damar Harsanto |

| Desk Editors | : | Pandaya, Imanuddin Razak |

| Art & Graphic Design Head | : | Budhi Button |

| Photographer | : | Seto Wardhana |

| Technology | : | Muhamad Zarkasih, Mustopa |

| Multimedia | : | Bayu Widhiatmoko |