The recent Constitutional Court ruling that allows millions of adherents of indigenous faiths to state their beliefs on their ID card has raised expectations of an end to state-sponsored discrimination. The Jakarta Post writers Margareth S. Aritonang and Corry Elyda review the landmark ruling and its pitfalls. Our correspondents Bambang Muryanto in Yogyakarta and Apriadi Gunawan in Medan take a closer look at local native faiths.

A ritual conducted by a community of Sunda Wiwitan, a West Java indigenous faith that existed long before mainstream religions arrived, in the temperate town of Kuningan confounded a local civil registry official who acknowledged he had never heard of the faith before.

“What is it? Is it Hinduism or Buddhism?” Opit murmured as he turned to a woman wearing a hijab sitting next to him. “This is definitely not Islam… those people don’t look like Muslims either,” he added as he observed the men in black and women in white kebaya.

His eyes lingered on the conspicuous portrait of prince Madrais Sadewa Alibassa Kusumah Wijaya Ningrat, better known as Kyai Madrais, the priest and founder of the Akur Sunda Wiwitan Cigugur Kuningan, the largest community of Sunda Wititan. What began as a cordial conversation between Opit and his Muslim acquaintance escalated into a debate on whether Sunda Wiwitan was a religion or a cult.

The event commemorating the propagation of Sunda Wiwitan in Kuningan by 185 years ago was indeed odd as it was attended by government representatives, rights activists and scholars. The highlight was a public seminar on the controversies surrounding the ancestral religion.

Among the notable guests was Nia Sjarifuddin, an expert staffer from the presidential working unit on the implementation of the state ideology Pancasila (UKP-PIP). A longtime campaigner of religious freedom prior to her assignment to the UKP-PIP, she praised the recent ruling on traditional faiths as a “revolutionary instrument” that will pave the way for equal treatment of native faith believers by the state.

Most of all, it reflected the newfound freedom among the hundreds of Sunda Wiwitan who came from faraway towns such as Garut in Banten. That day, the Sunda Wiwitan and freedom of religion advocates came together to celebrate the Constitutional Court’s landmark ruling that allows native faiths to be stated on ID cards.

”The ruling has raised expectations that millions of native faith believers across the archipelago will be able to exercise their constitutional right to embrace the spiritual belief of their choice without fear or discrimination.”

For a half century, believers have been subject to arduous bureaucratic procedures and even rejection when applying for official documents such as birth certificates, marriage registries and ID cards. Many have been alienated by being forced to choose one of the six state-recognized religions so that they can exercise their civil and political rights. Only a few are courageous enough to leave the religion space on their ID cards blank rather than faking their faith.

In some cases, adherents of indigenous beliefs are often stigmatized as heretics. The local government in Brebes, Central Java, built a special cemetery for followers of native faiths after pressure from believers of the mainstream religions.

In Jambi, the local government sided with Muslim groups who forcibly closed a Sapta Darma house of worship in 2013 on the pretext that the Javanese belief system was heretical.

Persistent discrimination and the persecution of religious minorities has often invoked international criticism and blemished Indonesia’s reputation as a role model of a democratic Muslim-majority country.

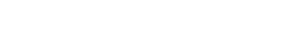

Indonesia, which is not a theocracy and proud to be the world’s third largest democracy, treats religious faiths as either state sanctioned or unrecognized. The underlying problem that the Constitutional Court was meant to deal with was the Law No. 23/2006 on civil registry that was amended in 2013, which retained its controversial provision concerning religion.

Traditional faith groups, namely the Marapu of East Sumba, Parmalim and Ugamo Bangsa Batak of North Sumatra and Sapta Darma of Yogyakarta, managed to convince judges that not recognizing local beliefs was a violation of the constitution. They successfully argued that traditional belief systems have the same place as state recognized religion in Indonesian politics.

The festive event that the Sunda Wiwitan and their supporters held late last month may have been premature. Technically, the court’s ruling is binding. However, strong undercurrents could sway the government, which is currently considering the best way to implement the ruling so as to not offend critics’ religious sensitivities.

Conservative leaders of mainstream religions have argued that the court’s ruling confuses religion with traditional faith. While the two systems share fundamental values, such as monotheism and the search of spiritual perfection, by the traditional definition they are distinctive. A religion, for example, is introduced by a prophet whose teachings are encapsulated in holy scriptures, has standardized rituals and transnational followings.

Accordingly, the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) has openly objected to allowing native faith followers to state a specific indigenous belief in the religion space on their ID card. Instead, MUI suggests that the government issue specific ID cards for traditional belief followers.

“The government should exercise due care in implementing the court’s ruling so as not to stir public unrest,” said MUI chief Ma’ruf Amin.

Leaders of the minority Christian, Buddhist, Hindu and Confucian faiths have chosen a more muted response to the sensitive issue.

The Education and Culture Ministry, the Home Ministry and the Religious Affairs Ministry are finalizing guidelines on implementing the court ruling in a manner that avoids controversy.

The question is whether citizens will be given the liberty of stating the name of their native faiths on their ID card, or have their faiths stated as Kepercayaan Terhadap Tuhan Yang Maha Esa (Belief in the Almighty God), regardless of what their native faith is.

The Home Ministry’s civil registration director general Zudan Arif Fakrulloh said it looks as though the government would prefer the second option, which may be less problematic because local belief systems are subject to change and even dissolution.

“In cases where [native faith’s] are dissolved, the adherents will have to have their ID cards revised. This means that we must review the data again,” he says. But this sentiment would clash with the presidential inner circle. Nia said she would like to see the ministries give citizens the freedom of stating their native belief on their ID card because that was what they have always been in search of. “There’s no reason not to implement the ruling,” she said. She predicted any backlash would likely come from leaders of mainstream religions who are afraid of seeing the number of believers decrease.

“Those people care about nothing but statistics.”

This year, the Culture and Education Ministry has registered 187 native faith groups that have 1,034 branches across the country, with followers numbering around 12 million throughout Indonesia.

Assuming the official figure is accurate, the court ruling will likely cause concern among leaders of the mainstream religions. The number of native faith believers could rise and those of the mainstream religions drop if every citizen states their true faiths on their ID cards.

According to the latest national census conducted in 2010, of the then 237.64 million Indonesians, 201.17 million were Muslim, 16.52 million Protestant, 6.90 million Catholic, 4.01 million Hindu, 1.70 million Buddhist and 117 thousand Confucian.

The court ruling that delighted rights advocates but dismayed conservative religious leaders remains a touchy issue. While preparing the bureaucratic system to accommodate the court ruling, the central government will have to educate local bureaucrats like Opit about the crucial development and what it means for civil servants.

Let there be no discrimination: Parmalim, or adherents of the Batak indigenous faith Ugamo Malim, attend a service at their house of worship in Medan, North Sumatra. Discrimination has forced many believers to pretend to embrace a state-recognized religion so that they can exercise their civil rights. (JP/Apriadi Gunawan)

Let there be no discrimination: Parmalim, or adherents of the Batak indigenous faith Ugamo Malim, attend a service at their house of worship in Medan, North Sumatra. Discrimination has forced many believers to pretend to embrace a state-recognized religion so that they can exercise their civil rights. (JP/Apriadi Gunawan)

Local faiths thrive in ‘center of Javanese culture’

It was cold and rainy on the night a group of about 25 followers of Sapta Darma, one of Java’s traditional faiths, were observed in deep prayer inside Candi Sapta Rengga. The melodious recital of Javanese poetry of customary wisdom that rose from their sanggar, or house of worship, imbued the evening with a mystical air.

Each Sapta Darma adherent was seated cross-legged on a rectangular piece of white cloth, their arms crossed and facing the sanggar’s east wall that was decorated with the symbols of their faith. The dominant among them was the image of Semar, a Javanese wayang character that symbolizes wisdom, placed next to the Sapta Darma logo.

It was the night of the sujudan ritual, which was attended by the Sapta Darma followers who comprised the organizing committee for a grand gathering later this month. Hundreds of believers from across the country are expected to attend the gathering at Candi Sapta Rengga, the Sapta Darma’s headquarters.

Sapta Darma is one of about 300 organized indigenous faiths in the country, according to the Indonesian Indigenous Faiths Supreme Assembly (MLKI). Sapta Darma’s leaders claim it has about three million followers across the archipelago. Every five years, their leaders assemble at the Candi Sapta Rengga, a mansion formerly owned by the faith’s second supreme leader, Soewartini Martodihardjo. Soewartini, who is known by her honorific name of Tuntunan Agung Sri Pawenang, died in 1996 and was succeeded by the incumbent supreme leader, Soekoen Kartowijono.

The group was founded by an enlightened barber named Hardjo Sopoero, who was born on Dec. 27, 1914, in the East Java town of Pare. Hardjo was believed to have had a divine revelation in Pare on Dec. 27, 1952, after which he adopted Sri Gutama as his prophetic name. Upon his death in 1964, the priesthood was handed down to Soewartini.

Sapta Darma adherents follow seven precepts to achieve worldly and heavenly happiness: 1) be faithful to God the Almighty; 2) abide by state laws; 3) defend the country; 4) help anyone in need without expecting anything in return; 5) have the courage to live according to one’s own faith and strengths; 6) be polite, behave, become a role model in the family and in society; 7) be aware that the world is changing.

Yogyakarta, a city known as the center of Javanese culture, is home to dozens of indigenous belief systems. Only a few kilometers from Candi Sapta Rengga lies the headquarters of another native faith, Sumarah. In the center of the complex is a 10-meter-by-15-meter sanggar, tucked under shady sapodilla trees.

The property was originally owned by Sumarah founder Soekino Hartono, who was born in 1897 in the eastern Yogyakartan regency of Gunung Kidul. According to The History of Sumarah 1935-1970, published by the Culture and Education Ministry, the young Soekino kept changing jobs, from an aristocrat’s servant to a sugar factory worker, and to a bank employee, before he received divine inspiration.

In the Javanese language, sumarah means “self-submission,” which is the essence of the faith’s teachings. The Sumarah faith believes in the oneness of God, and its dogma is summed up in nine tenets: 1) believe that God exists; 2) follow God as the guiding light; 3) mind the consistency of words and deeds; 4) foster friendships; 5) fulfill obligations to society and the state; 6) abide by state laws; 7) reject bad deeds; 8) broaden knowledge; and 9) object to fanaticism.

Nugroho, secretary of the Sumarah Communion’s Yogyakarta chapter, saaid Sumarah has about 5,000 registered members, mostly in East Java. The faith also has overseas members like in Malaysia, the Netherlands and Australia.

Night prayer: Followers of Sapta Darma, the Javanese native faith that claims to have three million members across Indonesia, worship at their headquarters Sanggar Candi Sapta Darma, Yogyakarta.(JP/Bambang Muryanto)

Night prayer: Followers of Sapta Darma, the Javanese native faith that claims to have three million members across Indonesia, worship at their headquarters Sanggar Candi Sapta Darma, Yogyakarta.(JP/Bambang Muryanto)

Parmalim reflect on faking religion for rights

Parmalim Palace, a place of worship for the local followers of Ugamo Malim, an indigenous faith of the Batak, one of the biggest ethnic groups in North Sumatra, came to life on a recent Saturday as a congregation was streaming in for their routine mass.

Ulupunguan Rinsan Simanjuntak, who led the procession, slowly walked into the place of worship holding burning incense, followed by his parishioners. All of the worshippers were barefoot and clad in traditional Batak attire.

Women were dressed in kebaya with ulos cloth draped over their shoulders. Men wore western-style suits and donned local turbans. There was a different dress code for unmarried attendees — both men and women wore sarongs without headdresses and ulos. Inside, men and women were segregated. They chanted prayers while sitting cross-legged on the floor.

The Parmalim, as believers of the indigenous religion are called, performed the procession in their native Batak dialect. That day, they also prayed for an end to discrimination against all groups that have suffered.

Ugamo Malim is believed to be as old as the Batak themselves. Much of the credit for its survival through to modern history went to the clan of priest-king Patuan Besar Ompu Pulo Batu, aka King Sisingamangaraja XII (1849-1907). He was killed in a battle against Dutch colonial troops and was declared a national hero in 1961.

Since his demise, his priesthood has been handed down to successors in a tradition that has continued to this day. King Poltak M. Naipospos, who resides in the Ugamo Malim headquarters in Huta Tinggi, Toba Samosir regency, oversees Ugamo Malim traditions.

Ugamo Malim followers faced oppression under the New Order regime (1966-1998), which did not recognize native belief systems. The Parmalim, like other followers of native faiths, had to choose one of six official religions while applying for ID cards or risk being denied their civil rights.

A great many of them caved in, pretending to embrace state-recognized religions by registering under religions they did not adhere to in order to obtain ID cards. Rasdin Sijabat, a Parmalim who lives in Medan, said he risked being isolated from his community had he not done so.

“On my ID card, I identified myself as a Catholic even though everyone in our community knew I’m a Parmalim,” he said before attending an Ugamo Malim religious service. He registered as a Catholic to qualify for a job as a civil servant. Like many of his fellow Parmalim, Rasdin, a teacher, wants to change his religious identity on his ID card. “The time has come to show our true identity as Parmalim.”

Another Parmalim, Jonga Gultom, said that he and his family had been subject to alienation from his community before he registered as a Christian. “They eventually accepted us after I changed my identity to the Christian religion on my ID card,” said the 61-year-old.

Kasman Sirait, 62, said he once bribed a subdistrict official to issue a Christian ID card for his son, who wanted to join the police force in 2001. He said he knew that his son’s application would be rejected if he professed to follow the local belief.

“Unfortunately, my son failed the tests, but his ID card still today lists his religious identity as Christian.”

The Parmalim deem the recent Supreme Court’s ruling on recognizing the civil rights of followers of indigenous faith as a newfound freedom.

| Writers | : | Margareth S. Aritonang, Corry Elyda, Bambang Muryanto, Apriadi Gunawan |

| Senior Managing Editor | : | Kornelius Purba |

| Managing Editors | : | Primastuti Handayani, Rendi A. Witular, M. Taufiqurrahman, Damar Harsanto |

| Desk Editors | : | Pandaya, Imanuddin Razak |

| Art & Graphic Design Head | : | Budhi Button |

| Photographers | : | Bambang Muryanto, Apriadi Gunawan |

| Technology | : | Muhamad Zarkasih, Mustopa |

| Multimedia | : | Bayu Widhiatmoko, Citra Asih |