The Mahakam, one of Indonesia’s mightiest rivers, is home to endangered freshwater dolphins in Kalimantan. Conservation group Rare Aquatic Species of Indonesia (RASI) estimates their number at 80. Pollution from the mining industry and logging has been largely blamed for their endangerment. The Jakarta Post correspondent in Balikpapan, East Kalimantan, Nurni Sulaiman, recently joined researchers and activists on a three-week trip along the Mahakam River to monitor the animals’ degrading habitat and conservation efforts.

Sailing upstream from the provincial capital of Samarinda to Kutai Kartanegara, some 75 kilometers to the northwest, we passed countless vessels of all sorts. In Kalimantan, a vast but sparsely populated island, rivers are just like busy highways in the more developed Java.

In downstream areas closer to the estuary, staggering coal-laden bulk carriers looked like clusters of floating hills from afar. Further upstream, in the area of Ulu in Kutai Kartanegara, vessels carrying mostly timber are headed for sawmills dotting the 980-km long river.

Locals and researchers fondly remember sighting groups of dolphins along the Mahakam River from the upstream Kutai region down to the estuary in Samarinda. That was a few decades ago, when traffic on the river was light. Today, it is teeming with vessels of all sizes that environmentalists partly blame for the dwindling population of the treasured river dolphins.

At Sebembam, Kutai Kartanegara, The Jakarta Post and researchers sighted a pod of about 16 dolphins.

The thundering noise of an oncoming bulk freighter scared and sent them in disarray.

Danielle Kreb, a senior researcher and scientific advisor with RASI, said the heavy presence of vessels and the noise they make has greatly contributed to the endangerment of the rare species. Every time a vessel approaches, the dolphins dive deep into the river. “They don’t rise up as often as they used to; they have experienced a change in diving pattern.”

Research shows that the animals have gone through behavioral changes because of the noise pollution and deteriorating water quality due to the dust and debris from the passing vessels. Untreated waste from industrial activities along the Mahakam and its numerous water sources has exacerbated the predicament.

The busy traffic not only causes stress to aquatic life but also damages the river’s ecosystem, especially in narrow creeks where fish spawn.

The prolonged stress reduces the animals’ immunity and contributes to ailments and premature deliveries, changes in migration patterns and avoidance of excessively busy spots like tributaries. The latter results in fiercer competition for space and food. Besides that, the dolphins are at risk of being struck by speedboats, as excessive noise confuses their sonar system.

The underwater noise pollution from the busy river traffic is worst at confluences. One of the most affected is the Kedang Kepala tributary in Kutai Kartanegara, which is known as one of the few remaining Mahakam dolphin habitats. “This is very worrying,” said Kreb.

During their trip, the researchers focused on several important spots, such as those at the Kedang Rantau, Sabintulung, Tunjungan, Kedang Kepala and Siran estuaries. To our delight, dolphins were sighted in various spots along the way.

Kreb noted that the number of Mahakam dolphins in the Kedang Kepala River had dropped by 50 percent since pontoons began “invading” the area two years ago. The river has sustained damage to its banks, because it is too narrow for large vessels to make L- or U-turns.

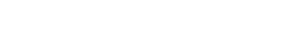

She expressed her wish that vessels be banned in the area, because it has been earmarked as a priority conservation area for not only water but also wasteland ecosystems.

“Residents have told me that the Mahakam’s current used to be stronger. This means the water quality has deteriorated. The loss of vegetation at the riverside has deprived small fish of spawning grounds. All this has happened over the past two years, since the strong presence of vessels began in the area,” Kreb said.

A study the RASI conducted at the Siran estuary and Kedang Kepala River from November 2015 to December 2017 shows that the level of underwater noise from passing vessels ranges from 87 to 93 decibels, high enough to cause stress in fish.

According to marine biologists Ralph H. Penner and Whitlow W. Au, any underwater noise above 80 decibels can disable dolphins’ sonar system, such that the mammals will lose their sense of orientation. They may lose the ability to measure their distance from objects like passing vessels. This poses a grave danger to the animals, especially in narrow creeks.

Various studies show that water traffic greatly interferes with dolphins’ daily activity, such as foraging, resting and socializing, and with their ability to depend on an eco-location signal to determine the bearing and location of other group members. Sustained excessive noise pollution is also bad for the mammals’ digestive and reproductive systems.

The Mahakam dolphin is widely thought to be of the same species as the Irrawaddy dolphin (Orcaella brevirostris) found in coastal areas in South and Southeast Asia, and in three rivers: the Ayeyarwady in Myanmar, the Mahakam and the Mekong.

However, Kreb — who has researched the Kalimantan dolphins locally known as pesut Mahakam for about 20 years — begs to differ. DNA analysis showed that the pesut was a totally different species, she said, proposing that it be scientifically identified as Orcaella mahakamensis instead.

For further verifications, the pesut DNA is currently being analysed in collaboration with the International Biodiversity Research Center in Bali and the University of Atmajaya in Yogyakarta.

“The Mahakam dolphin is unique. It lives in freshwater and has completely adapted to and evolved in freshwater. It has a distinct physical shape, bone structure and DNA […] all of which make the Mahakam dolphin more valuable [than the Irrawaddy]; and it really is on the brink of extinction,” said Kreb.

East Kalimantan is an industrial and resource-rich region, where 147 major companies operate mostly in the Kutai Kartanegara regency that accounts for much of the Mahakam dolphin territory.

At least two of them, PT Bara Tambang and Fajar Sakti Prima of the Bayan Group, operate vessels on the Kedang Kepala River since 2015, as does PT Bayan Resources, which also runs a jetty in the Belayan River.

It looks as though the disruption will only worsen. Goenoeng Djoko Hadi, a senior official with the East Kalimantan Energy and Mineral Resources Agency, told The Jakarta Post that Fajar Sakti Prima, a coal mining company, is presently building a 90-km coal-hauling path traversing the regencies of Kutai Kartanegara and West Kutai.

Fahmi Himawan of the East Kalimantan Environment Office is among those concerned about the adverse impacts of that project on the environment in the conservation area.

Fajar Sakti Prima had its license revoked for flouting environmental laws in 2015, but it has been reinstated by the provincial administration. That was after the company had convinced the local government it would comply with regulations and help protect the Kedang Kepala River, one of the pesut’s last bastions.

The minimum interval between coal pontoons traveling on the river is set at 30 minutes and a maximum speed of 8 knots, or 15 km per hour, when they are within 2 km of a tributary.

While those regulations sound good, there is no guarantee they are enforceable, because, as Fahmi admitted, the local administration is short of funding and human resources to oversee 10 townships and regencies. Locals say the sighting of pesut near residential areas anywhere along the Mahakam is increasingly rare in recent years.

Mulyadi, 40, a Dayak tribesman in Mahakam Ulu, said he had never seen one in his life. Coal mines, oil palm plantations and logging are blamed for the environmental degradation in general and the disappearance of the dolphins in particular. Aside from the water traffic, the Mahakam has been used for years to store logs before they are transported to saw mills.

At loggerheads: Loggers put their timber in the river before they are processed at numerous saw mills. Continuing deforestation has pushed Kalimantan’s exotic species to the brink of extinction. (JP/Nurni Sulaiman)

At loggerheads: Loggers put their timber in the river before they are processed at numerous saw mills. Continuing deforestation has pushed Kalimantan’s exotic species to the brink of extinction. (JP/Nurni Sulaiman)

Over the last 10 years, the RASI has recorded 32 dolphin deaths; three of those happened last year. The most common causes of death are unintended entrapment in gill nets and poisoning. Traditionally, local residents do not hunt for dolphins, knowing the animals are rare and legally protected.

Besides health problems presumably caused by excessive noise pollution, other major causes of Mahakam dolphin fatalities that researchers have identified include gill nets, beaching, river traffic accidents, problematic birthing, poisoning from domestic waste and coal mining, electrical fishing and predators.

The Mahakam dolphin’s lifespan is estimated at 30 to 40 years. The age of sexual maturity varies depending on gender. Males become sexually mature at 10-15 years of age and females at 5-13 years. Pregnancy lasts for about 14 months. Babies nurse a minimum of 1.5 years. Throughout its lifetime, a female dolphin can give birth approximately 10 times.

It will take a concerted effort between the government, conservationists, businesses and local residents to save the Mahakam dolphin. The latest scheme to develop ecotourism in river spots with dolphins as the main attraction is expected to support that endeavor.

Big and noisy: Coal mining activities, especially the transportation of coal using bulk freighters, have been blamed for heavy pollution in the Mahakam River. Loud noises coming from the vessels confuse the dolphins’ natural sonar.

Big and noisy: Coal mining activities, especially the transportation of coal using bulk freighters, have been blamed for heavy pollution in the Mahakam River. Loud noises coming from the vessels confuse the dolphins’ natural sonar.

Known as ‘human reincarnation’, dolphin highly revered

Traveling on the huge slow-flowing Mahakam River, where crocodiles roam free (seriously!), on a ces or ketinting (small motorized wooden boat) is both a fun and adventurous activity. The treacherous waves are so close to your side that sudden splashes occasionally hit your hands and face.

From its inconspicuous sources up in West Kutai to the busy estuary in Samarinda where it empties into the Makassar Strait, the Mahakam charms visitors with its network of rivers, lakes, creeks, deltas and tributaries among the tropical lush greenery.

Designated as an ecotourism destination, the 980 kilometer river boasts exotic flora and fauna that wildlife buffs should not miss, such as the rare Mahakam dolphins, birds and primates. While cruising on the boat, you can see some of them in the water, on trees and riverbanks.

From Jakarta, it takes two hours and 15 minutes by plane to Balikpapan and another two-three hours by car to Samarinda. From here, you can take a boat to explore the Mahakam. For pesut watching, it is recommended that you find a guide that can take you to the rights spots.

From Jakarta, it takes two hours and 15 minutes by plane to Balikpapan and another two-three hours by car to Samarinda. From here, you can take a boat to explore the Mahakam. For pesut watching, it is recommended that you find a guide that can take you to the rights spots.

I was so lucky that my group sighted pods of pesut, as locals call the dolphins, in several spots. We saw the smart animals swim around while feeding and playing. Many of them are families of mothers, babies and juveniles.

In the lush green panoramic tropical rain forest nearby, proboscis monkeys leap from one tree to another. Storks fly low and danced overhead.

Thriving ecotourism has given rise to sightseeing tours in local towns and villages. Travel agents offer packages that include pesut watching. One of the tour groups is called Save Pesut Mahakam. Trips are even more enjoyable with the availability of floating eateries in addition to the more conventional inland food stalls.

Tour guides are well-versed about local species and places to find them in the wild. They are the right people to show you spots where dolphins usually assemble. The ecotourism destination has attracted people far and wide, including the Netherlands, Germany and Australia.

The dolphins have their own spots to feed and play. Among the best-known are tributaries and lakes between Muara Kaman and Melak — the mammal’s main habitat. There lie four major tributaries where the animals are often sighted: Pela, Belayan, Kedang Kepala and Kedang Rantau.

Of all the places we visited, I found Sangkuliman, a fishing village by the Pela River, the best place for dolphin watching. You can stay on a floating guesthouse from where you can see them move about, especially in the early morning and afternoon. At dusk, the place is famous for its sunset.

Another place to watch dolphins is the confluence of Muara Kaman village in Kutai Kartanegara, where they appear while you enjoy lunch at an unpretentious restaurant. Muara Kaman and Sangkuliman are known as a route of the pesut migration.

Regarded as the most valuable conservation areas are the Pela, Kedang Kepala and Kedang Rantau rivers, where visitors can find endangered species such as proboscis monkeys, lesser adjutants, leaf monkeys, macaques and the majestic hornbills.

The Pela River connects three major lakes: Semayang, Melintang and Jempang, which are the dolphins’ favorite socializing and feeding sites. If you are lucky, you may see the pesut give birth there, says Danielle Kreb, senior researcher and scientific advisor with the Rare Aquatic Species of Indonesia.

The Jempang Lake is the most happening with the bustling fishing communities. Here, the main tourist attraction is the cultural village of Tanjung Isuy, where the Dayak tribes, the Tunjung and Benuaq, live in longhouses that are available as tourist accommodation. The village is also famous for its handicrafts.

A great thing about the local tradition is that locals do not hunt dolphins. The animal is highly treasured as the province’s icon. Their high regard is embodied in folklore which says that the animals are the reincarnation of humans and therefore killing or trading them is taboo.

Mansyursyah, a 56-year-old Kutai tribesman, says he believes in the folklore after personally seeing dolphins beached at a riverbank. “Their bodies looked like a human’s,” he said. “The female’s body very much resembled a women’s body.”

The Mahakam fresh water dolphin, whose number is estimated at about 80, is legally protected under Law No. 5/1990 on conservation of biodiversity and the ecosystem.

Kalimantan has long been regarded as a haven for ecotourism. Orangutans, which have also been listed as endangered, has long been the traditional attraction. Tourism is expected to underpin the conservation effort, generating income for many locals and improving their ecological awareness at the same time.

Other than the animals, Kalimantan is famous for its natural beauty and exotic, diverse Dayak culture. Floating markets charm visitors from outside the sparsely populated island.

Monkey business: The bekantan (proboscis monkey) is endemic to Kalimantan. Logging and land clearance to make way for oil palm plantations have endangered the island’s biodiversity. (Photo: Courtesy of RASI)

Monkey business: The bekantan (proboscis monkey) is endemic to Kalimantan. Logging and land clearance to make way for oil palm plantations have endangered the island’s biodiversity. (Photo: Courtesy of RASI)

| Writer | : | Nurni Sulaiman |

| Senior Managing Editor | : | Kornelius Purba |

| Managing Editors | : | Primastuti Handayani, Rendi A. Witular, M. Taufiqurrahman, Damar Harsanto |

| Desk Editors | : | Pandaya, Imanuddin Razak |

| Art & Graphic Design Head | : | Budhi Button |

| Technology | : | Muhamad Zarkasih, Mustopa |

| Multimedia | : | Bayu Widhiatmoko |