Despite its reputation as a resource-rich country, Indonesia still bears

the shame of a problem with stunting, globally having the fifth highest number of cases. The Jakarta Post journalist

Moses Ompusunggu examines why Indonesia remains struggling with the issue and what it is doing to address it.

Recently, an auditorium at the Health Ministry in South Jakarta was jam-packed with hundreds of health experts attending a conference called Doctor’s Parade. The day’s star speakers were eight scientists who had just obtained their doctoral degrees from various universities.

Among the most awaited presentations from scientists representing government bodies were two nutritionists who would reveal the results of their studies on stunting.

The conference took place at a time when Indonesia is struggling to address the chronic health problem. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines stunting as the impaired growth and development that children experience as a result of poor nutrition, repeated infection and inadequate psychosocial stimulation. Undernourishment is the leading cause of stunting.

Stunted children have poor cognitive abilities and undersized brains, which in turn can impair their ability to learn. Their resulting cognitive abilities will likely hamper them from competing for decent jobs in adulthood.

Scientists have also found that stunting is responsible for deaths from infections like pneumonia, diarrhea, meningitis, tuberculosis and hepatitis. In part, it is because stunted children, especially those with severe developmental impairment, develop poor immune systems.

“The interplay of poor nutrition

and frequent infection leads to a vicious cycle

of worsening nutritional status

and increasing susceptibility to infection,”

~WHO nutritionists Mercedes de Onis and Francesco Branca

wrote in the Maternal & Child Nutrition Journal in 2016.

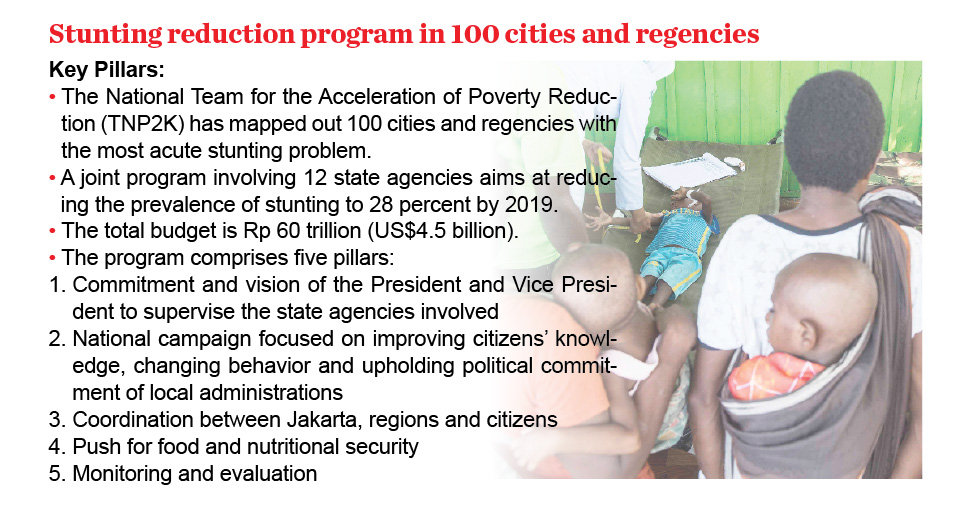

In Indonesia, stunting remains chronic despite its emerging economy status and puts it in the league of five countries, namely India, China, Nigeria and Pakistan, with the most cases, according to UNICEF’s 2009 study.

“Stunting is a long standing problem that puts our future generations at risk,” Hendrayati, a nutritionist with Makassar Health Polytechnic in South Sulawesi and one of the authors on stunting addressing the conference, said.

“That is because stunted children will likely have a higher risk of developing various health problems during adulthood.”

Indonesia may be renowned for its natural resources but its efforts to rid stunting have brought shame. The Health Ministry’s latest basic health study, which is conducted every five years, found that 37.5 percent, or around nine million, of children aged below five nationwide were stunted or severely stunted in 2013.

According to the WHO, stunting is a public health problem in a particular country if its prevalence reaches 20 percent or above. A 2014 estimate by the United Nations Statistics Division, meanwhile, showed Indonesia’s figure of 37.5 percent of children aged below five being stunted was the highest in Southeast Asia.

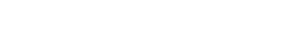

Dismayed, President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s stepped up efforts last year, ordering 12 ministries to team up and bring down the rate to 28 percent by 2019 — the last year of his first term in office.

For the interdepartmental endeavor, the government is allocating about Rp 60 trillion (about US$4.5 billion). Priorities go to 100 regencies and cities with the highest prevalence of stunting.

Given the immense challenge, even some government officials are skeptical the target can be achieved. Kuwat Sri Hardoyo, secretary of the Directorate General for Public Health, for instance, sees the initiative as too ambitious.

“It is easy to create interdepartmental coordination but the real problem is to transfer the knowledge to regional administrations,” Kuwat said in a recent interview.

Health officials in regions have complained they are struggling to implement intervention programs because locals are unaware of the need to provide nutritious food to their children from an early age for their physical and mental development.

In West Kalimantan, one of the priority areas, stunting is traditionally regarded as hereditary rather than a result of malnutrition.

“There, people don’t see it as a problem,” said Yulsius Jualang, head of West Kalimantan Public Health Agency.

The ignorance has been blamed on the high prevalence of stunting among children aged below five in the province. At 34.9 percent, the rate is much higher than the national average of 27.5 percent.

Official figures show that 32.5 percent of children aged under two in West Kalimantan were stunted in 2016, while among those aged between two and five years old the figure was 34.9 percent.

Some experts have also blamed persistent malnutrition and related health problems in many regions on the lack of a varied diet. “Sago, corn and sorghum are a good source of carbohydrates but they are less useful if people don’t consume other foods for other nutrients,” Dwi Andreas, a food expert from Bogor Institute of Agriculture (IPB) said.

Malnutrition is prevalent in isolated far-away regions, where people have limited access to safe and healthy food. The ongoing health crisis plaguing Asmat regency in Papua is a case in point where the government should ensure food security, he said.

Yet if you think that stunting is typical in far-flung regions, think again. The government is honest enough to admit that it is also a health problem commonplace on Jakarta’s doorstep.

In Bogor, for example, the Health Ministry’s study on 920 children aged below four in 2017 found that nearly one-third were stunted.

The study, which monitored the development of babies from pregnancy until they reached the age of four in 2016, also found the mothers of the diminutive babies had also been stunted because of poor nutrition. The maternal issue, it turns out, raises the odds of giving birth to a stunted child.

Women less than 150 centimeters in height have a 40 percent chance of having stunted children while anemic mothers’ probability is 20 percent, according to Erna Nuraini, a public health expert from the Bogor Health Agency.

Experts suggest taking iron supplements to reduce the risk of anemia during pregnancy, a health issue also attributed to preterm births.

The government also plans to supply an estimated 20 million teenage girls nationwide with iron tablets, focusing on senior high school students. It is part of the Rp 60 billion stunting eradication program for 100 regencies and cities.

“We are trying to ensure that all teenage girls in the 100 regions receive the iron tablets and all malnourished toddlers receive the additional nutritional food. Hopefully, it will reduce our stunting figures significantly,” Kuwat said. In her study last year, Hendrayati found that enriching children’s diet with zinc and protein-rich foods was highly recommended.

She studied the effect of zinc and cysteine, an amino acid that can be synthesized by the body, supplements on children who had been provided with a high-dose of vitamin A. Her conclusion was that the supplements can boost their linear growth.

High-dose vitamin A supplements are one of the government’s nutritional interventions given twice a year to ensure children’s normal growth. “We have seen a lot of efforts supported by the government but the results still fall short of expectations,” said Hendrayati.

Zinc is found in fish, red meat, oyster, crab and shellfish. Protein rich foods like meat and seafood also contain a considerable amount of zinc. In fact, Indonesia’s food resources are so abundant that malnourishment accounts to irony. Across the archipelago, regions have their own traditional staple food such as corn, sago, sorghum and tubers.

As Hendrayati put it, “Indonesia is rich in food resources, but few people make the best of it.”

Why babies’ first 1,000 days are critical to their growth

Health experts from all over the world have been trying to satisfy their curiosity about whether stunted infants can actually reverse their condition when they are between childhood and adolescence.

Although some studies have indicated this is possible, the globally accepted hypothesis is that stunting is largely irreversible after children celebrate their second birthday.

Andreas Georgiadis and Mary E. Penny from Brunel University in London wrote on The Lancet science magazine last September that even though some findings had indicated nutritional interventions in adolescent girls could break the “intergenerational cycle of poor growth”, the conclusions are still subject to further research.

“The mechanism by which intergenerational benefits might be realized through intervention at this age is unclear,” the two wrote in their article, referring to adolescence.

The first 1,000 days between conception and a child’s second birthday, they wrote, “have been identified as the most crucial window of opportunity for intervention.”

Why are the first 1,000 days so crucial? World Health Organization nutritionists Mercedes de Onis and Francesco Branca wrote in 2016 that the average length-for-age score among infants in deprived populations continues to decline until around the age of 2, considering that healthy infants experience “maximal growth velocity” during the first few months of life.

Damayanti Rusli Sjarif, a senior child nutritionist from the University of Indonesia (UI), Jakarta, said during that period, children develop 95 percent of their brain nerves, which supports their growth and cognitive development aspects like vision, speech, emotion and logic.

“The first 1,000 days of life, including the 279 days of pregnancy, is a crucial period for a child’s development,” said Damayanti, who also works as a pediatrician at Cipto Mangunkusumo General Hospital (RSCM) in Jakarta.

Indonesia, home to around 9 million stunted children, has given stunting prevention a top priority. When observing National Nutrition Day on Jan. 25, the government used the event to launch an information campaign on the importance of children’s “first 1,000 days”.

“We have been commemorating National Nutrition Day for more than a half century, and hopefully this year can bring momentum to better the nation’s nutrition status,” said Anung Sugihantono, the Health Ministry’s director general for public health.

The government hopes that nutritional intervention during the first 1,000 days can contribute to a 30 percent reduction in stunting prevalence in the country. The measures will be implemented in 100 regencies and cities that have a prevalence of stunting higher than the national rate of 37 percent.

In an official document that serves as a guideline of policy implementation, the government plans “specific intervention” and “sensitive intervention”. The former consists mostly of the provision of high-quality food supplements while the latter comprises the development of health-related infrastructure, like sanitation and water supplies.

The “specific intervention” targets pregnant women, who will be entitled to additional foods to remedy health issues caused by the lack of energy and chronic shortage of protein and iron. Moreover, the supplements are effective in protecting them from malaria.

The “sensitive intervention” is aimed at women who breastfeed babies aged 1 day to 23 months. This group will receive information about the importance of breastfeeding and a complete set of immunizations. They will also receive zinc supplements.

While the detailed intervention programs for the first 1,000 days have been available, one chronic problem remains: the lack of awareness among the public on how poor nutrition leads to stunting in children.

“Stunting often goes unrecognized in communities where short stature is so common that it is considered normal,” WHO nutritionists De Onis and Branca said in a report on their studies.

Often, people are only aware of nutritional problems after noticing their children are unusually thin.

Government surveys suggest that the majority of Indonesian families lack knowledge on nutrition and healthy lifestyle, and that women — highly susceptible to the adverse effects of undernutrition — are ignorant about the importance of nutrients.

A ministry-sponsored basic health survey in 2013 found that of around 89 percent of pregnant women who received blood iron tablets, only 33 percent consumed the minimum standard of 90 tablets during pregnancy.

“Pregnant women need to consume a lot of foods containing iron to ensure linear growth of the baby. If not, they risk having malnourished babies, something that’s difficult to tackle later on,” said Damayanti.

According to the ministry’s 2016 nutrition status monitoring, only 54 percent of Indonesian infants aged 1 day to 5 months enjoyed adequate breast milk.

“For many years, the government has overlooked education for mothers about the danger of undernutrition to their children,” said Esti Wijayati, a member of the House of Representatives commission on health and education.

Ignorance about the importance of nutrition to infants is also common among middle- and high-income families.

“Busy mothers sometimes feed their children instant noodles instead of vegetables,” Esti said.

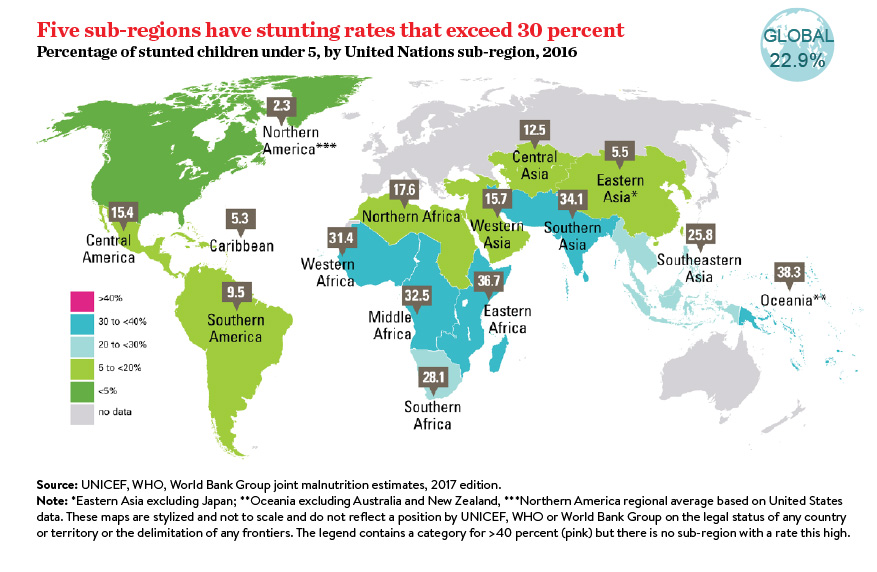

Chronic issue: A malnourished child undergoes medical treatment at the Agats General Hospital in Asmat, Papua. Malnutrition remains widespread in the underdeveloped province. (Antara/M. Agung Rajasa)

Chronic issue: A malnourished child undergoes medical treatment at the Agats General Hospital in Asmat, Papua. Malnutrition remains widespread in the underdeveloped province. (Antara/M. Agung Rajasa)

| Writer | : | Moses Ompusunggu |

| Cub Reporter | : | Vela Andapita |

| Senior Managing Editor | : | Kornelius Purba |

| Managing Editors | : | Primastuti Handayani, M. Taufiqurrahman, Damar Harsanto |

| Desk Editors | : | Pandaya, Imanuddin Razak |

| Art & Graphic Design Head | : | Budhi Button |

| Technology | : | Muhamad Zarkasih, Mustopa |

| Multimedia | : | Bayu Widhiatmoko |