Since rabies was declared endemic to East Nusa Tenggara in 1997,

there has been little progress in the provincial government’s efforts to eliminate the zoonotic disease, as the virus remains a serious health issue today. Reporting from Maumere, The Jakarta Post contributing writer Djemi Amnifu explains how the local government’s neglect, combined with the locals’ appetite for dog meat, has contributed to the spread of the deadly disease.

It has been two decades since the impoverished province of East Nusa Tenggara made a commitment to eradicating rabies, a disease transmitted from animals to humans, yet little has been achieved. Rabies, which is mostly transmitted by rabid dogs, remains prevalent on the main islands of Flores and neighboring Lembata. Over 250 deaths from the disease have been reported since then.

Inter-island canine traffic is common throughout the archipelagic province, especially on Flores and Lembata, making the spread of the disease even harder to track. Every year, the provincial government makes available up to 250,000 vials of rabies vaccines. However, sterilization and culling have brought an insignificant impact so far. Local folks’ bond with their best friends is so strong that when the authorities cull, people hide their dogs in the forest.

Government authorities are focusing on containing the disease on Flores and Lembata. The nearby islands of Sumba, Alor, Timor, Sabu and Rote remain rabies-free, said Dany Suhadi, the head of the provincial husbandry office.

Rabies, which scientists say is a 100 percent

vaccine-preventable viral disease,

is endemic to 24 of Indonesia’s 34 provinces,

with East Nusa Tenggara and Bali having the highest rates,

according to the Health Ministry.

The World Health Organization said that rabies was endemic to all continents but Antarctica, with Asia and Africa reporting 95 percent of the tens of thousands of deaths that occur worldwide every year.

Across Southeast Asia, WHO estimated that 25,000 people die from the disease every year. It aims to eliminate it by 2020 in collaboration with the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Organization for Animal Health.

WHO noted that about 80 percent of global fatalities happened to children in rural areas, where awareness of the disease is lacking and access to proper medical treatment is limited or non-existent.

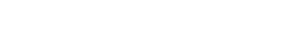

In East Nusa Tenggara, the first case of rabies was reported in 1997. The virus presumably came from Sulawesi and quickly spread to eight regencies on islands in the province, starting on Lembata and spreading to Sikka, Ende, Ngada, Nagekeo, East Manggarai, Manggarai and West Manggarai.

On Flores and Lembata,

99 percent of human rabies infections are caused

by dog bites and the rest by cat and monkey bites,

according to the provincial health agency.

The virus is transmitted via the rabid animal’s saliva through a wound and it replicates once it reaches the brain. Symptoms of rabies infection include headache, lack of appetite, vomiting, disorientation, restlessness, foaming at the mouth and hydrophobia or fear of water.

“Death usually comes in a matter of days after a person or animal shows clinical symptoms,” Dany said.

Since rabies began to spread on Flores and Lembata in 1997, local health authorities have recorded 43,360 cases of dog bites and 252 deaths. It is believed that the actual figures are higher. Cases are under-reported as few victims, especially those living in remote areas, report to health authorities.

Dogs as delicacy

The husbandry agency estimates the number of dogs on the islands of Flores and Lembata at 400,000. Dogs play an important role in the local culture. People in the Christian majority region use certain breeds for hunting and others for their meat.

Hendrikus Sali, the head of the Sikka regency agriculture, plantation and husbandry agency, said the government’s effort to eliminate rabies was hampered by the locals’ well-known penchant for dog meat. The market demand for the meat is forever high.

People only slaughter vaccinated dogs for obvious reasons and the practice gives the local statistics agency a hard time keeping records on the number of immunized canines.

In Sikka, home to an estimated 50,000 dogs, the immunization of dogs occurs every three months. The regency is worried that the population will continue to rise, which would increase the burden to immunize, as the animal gestation period is only two months, with the number of newborns reaching six.

Sikka serves as an example for rabies prevention. In 2014, its regent issued a bylaw on rabies control that required a swift response from government authorities. In 2017, Sikka recorded 10 cases of rabid dog bites with no fatalities. As of March this year, the cases have risen to 21 with no fatalities.

Interdepartmental quick response teams have been formed at every administrative level, from the regency down to the village, with clear standard operating procedures.

Teams consist of officials from the agriculture, plantation and husbandry agency, which handles the rabid dogs, and the health agency, which is in charge of medicating the victims.

In response to the crisis, Sikka has designated five of its 25 clinics throughout its 21 districts as rabies centers. Dog-bite victims are referred to different rabies clinics depending on the region: Watubaing in the east; Bola in the south, Lekebai in the west; Palue on Palue Island; and Beru, in central Sikka.

The five clinics are where dog-bite victims go for medical help and where people have their dogs and other pet animals vaccinated regularly. “They were chosen because they are the most easily accessible [rabies centers] for most people in each region,” said Harlen Hutauruk of the Sikka Health Agency.

Flores and Lembata have agreed to improve coordination to make the rabies eradication program more effective, using the Sikka bylaw as a common guideline. So far, the effort focuses on preventive measures in the form of dog vaccinations, sterilization, selective culling and information campaigns.

Asep Purnomo, the secretary of the Flores-Lembata joint rabies mitigation agency, said the program needed well-planned joint actions involving all regencies to succeed.

“Until the joint effort succeeds, we will be haunted by fears of preventable death,” he said. “People would have to spend a lot of money to fight off rabies.” A measure local authorities are considering is to provide every dog with a husbandry agency-issued tag containing information about the owner and most recent vaccination.

“Any dog that wears no identity tag can be legally killed for the sake of the common good,” Asep said. “The owner should be held legally responsible if their rabid dog bites anyone.”

Curative measures have proven costly and ineffective. Victims need at least four vaccine shots that cost them Rp 1 million. Fortunately, the local government pays for such medical expenses, but Asep warned that in the long run, the government would not be able to shoulder the burden alone and would have to share it with victims.

“Now, we [local government] are acting like firefighters who are running out of water.”

Tourism threatened

The persistent rabies problem on Flores and Lembata has left the tourist sector nervous. Large dog populations have caused security concerns for not only visitors but also vulnerable Komodo dragons, East Nusa Tenggara’s main tourist draw.

Since it was declared one of the New Seven Wonders of Nature in 2013, Komodo National Park has seen 1 million visitors every year, according to official figures. The prehistoric animals live in their natural habitat on the savannah islands of Komodo and Rinca, west of Flores.

“Unless rabies can be contained, even the giant lizards can be in danger,” East Nusa Tenggara tourism office chief Marius Ardu Jelamu told The Jakarta Post. He said there were two problems currently plaguing local tourism. First, because Labuhan Bajo, the main town closest to the national park, has no star-rated hotels, most international tourists stay on their cruise ships. This means that the visitors spend less money.

Second, the unresolved rabies epidemic has discouraged holidaymakers from visiting East Nusa Tenggara, specifically the national park, which has been designated one of Indonesia’s 10 best destinations.

The health issue is impacting not only national Komodo National Park and Rinca Island but also other major tourist spots like Ranamese Lake in East Manggarai, Kelimutu Lake in Ende, Oceanic Park of Riung Island in Ngada and Maumere Bay in Sikka.

Unless East Nusa Tenggara makes a breakthrough in combating rabies, the health issue will likely stay and keep tourists at bay.

Timely treatment key

to saving lives of rabies victims

Marino Yastian, 8, was playing alone outside his house in Riit village, some 25 kilometers from Maumere, Sikka regency, East Nusa Tenggara, at dusk when a black dog appeared out of nowhere and viciously attacked him. Upon hearing his screams, his mother Yasinta Sengsara, who was helping a neighbor load timber onto a truck nearby, rushed to his aid, hitting the animal with a lump of wood. The dog ran away, leaving her first-grader son badly injured.

“Blood streamed down his face when I picked him up and rushed him to the Puskesmas,’’ Yasinta said, referring to the community health center 10 km away. She became even more scared upon hearing from local people that the dog was rabid and known to have bitten another dog a few days before, and this was confirmed by Margaretha Siko, a veterinarian who heads the Sikka animal health section.

Marino received 10 stitches for a wound under his right eye and another three stitches for a cut on his lip. When The Jakarta Post visited him at Hillers General Hospital in Maumere in March his face was still bandaged. He said the wound under his eye was painful. It was his seventh day in hospital.

Recovering: Marino Yastian (center) is shown with a bandage over his right eye, which was seriously injured in an attack by a rabid dog at his home in March. The young boy did not contract rabies thanks to the swift medical treatment he received. (JP/Djemi Amnifu)

Recovering: Marino Yastian (center) is shown with a bandage over his right eye, which was seriously injured in an attack by a rabid dog at his home in March. The young boy did not contract rabies thanks to the swift medical treatment he received. (JP/Djemi Amnifu)

His relieved doctors repeatedly said it was a good thing that Marino did not contract the rabies virus thanks to the quick medical help he had received.

Medics at the village Puskesmas had administered two vaccine shots the night he was attacked, before he was taken to the hospital for further intensive care. Riit village chief Thobias Susar said the rabid dog bite was the first such incident to have occurred in the area and he planned to write to the Sikka administration asking for a mass vaccination of local dogs.

Harlen Hutauruk, head of the local health agency, praised Yasinta for quickly rushing Marino to the nearest clinic for medical help thus saving his life. The bites were so close to the boy’s central nervous system that delayed treatment would have meant death from serious neurological damage.

She said the boy would have faced dire consequences had the rabies virus, transmitted through the animal’s saliva, reached his brain and traveled and infected various organs. Once a bite victim shows symptoms, death is imminent because there is no known cure.

On the Post’s visit, Marino had been treated with a total of three shots of anti-rabies vaccine. His doctors said his last dose would be administered 28 days after the bite.

The conventional vaccine regimen recommends five shots within the 28-day span but more recent research has found that four shots will do. The two vaccine shots helped prevent the viral infection that could have been fatal once symptoms developed.

In rabies-endemic areas, children are especially vulnerable, mainly because they are less fearful of animals than adults. Their small stature also means they are likelier to get bites in the face, from which the virus travels to the brain more quickly.

Children can also contract the virus if they are scratched by rabid animals that lick their claws, or if they touch their mouths or eyes with a hand tainted by the saliva of rabid animals.

The virus causes fatal brain swelling but scientists say the vaccine is fully effective, provided it is given in time. The government has required that pet animals especially dogs and monkeys be vaccinated on a regular basis.

Tied up: In East Nusa Tenggara, long-tailed macaques like this one are widely kept as pets. The local government

Tied up: In East Nusa Tenggara, long-tailed macaques like this one are widely kept as pets. The local government

has asked residents to have their monkeys vaccinated against the deadly rabies virus. (JP/Djemi Amnifu)

| Reporter | : | Djemi Amnifu |

| Photographer | : | Djemi Amnifu |

| Managing Editor | : | Primastuti Handayani |

| Desk Editors | : | Pandaya, Imanuddin Razak |

| Art & Graphic Design Head | : | Budhi Button |

| Technology | : | Mustopa, Sandy Riady Hasan |

| Multimedia | : | Bayu Widhiatmoko |