Farms and plantations’ heavy dependence on pesticides is sounding an alarm on occupational safety in North Sumatra, one of Indonesia’s main oil palm producing regions. Some of the banned active chemical ingredients are widely available on the black market, while workers and farmers are ill-informed about the dangers of agricultural chemicals, reports The Jakarta Post’s local correspondent, Apriadi Gunawan.

A coterie of farm workers were sitting under the shade of oil palms as they took a break at a plantation in Tanjung Morawa subdistrict, Deli Serdang regency. The day was steamy and the breeze blew a whiff of the pesticides they had applied on crops of the 900-hectare estate controlled by PT Lonsum, one of the largest agricultural enterprises in Indonesia.

As they joked, a man carrying a pesticide spray tank on his back whizzed by on his bicycle, smiling at them. They called him pak Yadi, a 53-year-old rice farmer and their good neighbor in a nearby village. He passes by the estate every day.

What was shocking was that none of the men who handle pesticides every day wore any protective clothing, even when they are spraying the agricultural chemicals. That day, the workers had just sprayed herbicides to kill weeds in the plantation, and pak Yadi was on his way to his farm to apply pesticides to control insects that swarmed his paddy field.

The plantation’s pesticide applicators acknowledge that they do not usually use protective gear and equipment that can help them lower the risk of poisoning and minimize exposure to pesticides, while the management has yet to strictly enforce the rule. They say they know local farmers like pak Yadi did not bother to put on a protective suit that would minimize the adverse impact of the poison.

One of the workers, Tugimin, has worked for PT Lonsum for 27 years and says he rarely saw pesticide applicators wear the gear until very recently — when the management told them they had to use the gear because the company’s safety standards would be audited.

“They [the management] insisted that workers do it. Before that, few of us cared to wear [protective gear] when working in the field,” he said.

They knowingly fail to properly protect themselves

from pesticide poisoning for a myriad of reasons,

some pretty comical, such as discomfort, wrong size,

foggy glasses and helmets that are too heavy.

A PT Lonsum field supervisor, Herianto, confirms the plantation uses pesticides to control pests, but insists that it requires all chemical applicators to wear the standard protective suits and personal equipment.

“We give every worker protective clothes and equipment when they are applying pesticides,” he says. “We often train them on how to work with the safety gear.”

Standard occupational safety measures like the use of protective suits and equipment when mixing, loading and applying pesticides is made mandatory by Manpower and Transmigration Ministerial Decree No. 08/2010, but poor enforcement has led to ignorance.

Like in other less-developed countries, pesticides are widely used in Indonesia. While in many cases the chemicals are not adequately tested for safety, they have been known to pose a serious danger to human health and environmental degradation.

The term “pesticides” encompasses countless chemicals created to kill unwanted animals, like insects (the chemical is therefore called insecticides), fish (piscicides) or rodents (rodenticides), and unwanted growths like fungi (fungicides) and weeds (herbicides).

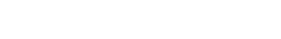

The government has banned 36 active chemical ingredients from being used in pesticides for their known menace to humans and the environment. Residues of commonly applied insecticides in food have been linked to various health issues, such as cancer, birth defects and learning impairment.

Chemical pesticides are also known to pollute the environment. Numerous studies have found that they remain in the soil, waterways and air long after use. Unmeasured use often causes collateral damage. Residues build up and contaminate the environment and may cause health issues.

Indispensable

In Karo, North Sumatra’s idyllic cool plateau and largest vegetable producer, farmers’ heavy, decades-long dependence on chemical pesticides has coined its own axiom: “No pesticide, no sale.”

“Without pesticides, no vegetable and fruit plants would grow here,” says Pelin Depari, a middle-aged man who has been growing vegetables most of his life. He claims he knows of other farmers who use insecticides with active ingredients that the government has banned.

People in the industry say that prohibited pesticides are available only on the black market, and demand is lower notably because they are too expensive for most farmers.

The banned Dikloro difenil trikloroetana (DDT), which could be bought for Rp 80,000 (US$5.66) per kilogram a few years ago, costs more than Rp 100,000 per kg today. It remains highly sought after for its potency in eradicating insects. Erwin Masrul Harahap, a lecturer at Sumatera Utara University’s School of Agriculture, says farmers have depended on pesticides of decades and it would likely continue because the chemicals remain indispensable to manage insects and weeds. Unfortunately, forbidden pesticides can still be easily purchased in the black market.

“Farmers are the main buyers of banned chemicals in the black market,” he says.

Among the widely available contraband is DDT and Endrin, which are so hazardous they can kill humans. However, they are the most effective.

Traditional farmers like Pelin are well aware of the danger of pesticides, especially those the government banned in 2007.

“But the problem is that farmers don’t have any other choice to protect their crops from pests than to use pesticides,” he says.

The best they can do is to scale down their use.

Organic pesticides — made from natural ingredients — are not as popular. They work slowly and are ineffective in eradicating a pest attack. Also, a much higher dose is needed to achieve the desired effect and they require a more intricate storage procedure to maintain efficacy. Besides, organic pesticides cost more than synthetic ones.

In short, they are neither effective nor efficient for large-scale use. Environmentalists advise that farmers use chemical pesticides only when crop damage caused by pests reaches the threshold level.

What ban?

A recent study by the Organization for People’s Struggle and Empowerment (Oppuk) and Pesticide Action Network Asia and the Pacific (PAN AP) has confirmed the widespread use of pesticides that contain banned active ingredients in North Sumatra.

Oppuk researcher Lambok Simbolon says that in South Tapanuli regency, plantation enterprise PT ANJAS, which employs about 1,300 workers, was found using Gramaxone, which contains active ingredients the government prohibits. The same product was also used by PT ABM, a major oil palm plantation in South Labuhan Batu regency, which employs more than 1,600 workers.

“Gamaxone is one of the most dangerous pesticides widely used in plantations in the region,” Lambok tells The Jakarta Post.

Oppuk executive director Herwin Nasution says the lack of awareness on the need to use proper protective clothing and equipment among pesticide applicators is the result of the government and corporate authorities’ failure to spread the state policy on occupational safety and health to workers. The 2007 official ban on 41 active chemical ingredients has also yet to be adequately informed to the public.

During the study, researchers found 42 cases of pesticide poisoning among applicators. Most common symptoms include headaches, dizziness, vomiting and respiratory difficulties.

PT Lonsum workers in Tanjung Morawa agree with the findings. Mesiem, a 64 year-old woman who has worked as a pesticide applicator with the firm for 20 years, says she has never heard about the ban. Her colleague, Jumiarsih, 40, an herbicide applicator, does not know about it, either.

The North Sumatra chapter of the Indonesian Palm Oil Producers Association (Gapki) claims it was unaware that any of its 82 members use banned pesticides, given the well-known adverse effects to both the plants and human health.

“Pesticides injected into the plants or sprayed onto them can find its way into the fruit, which can pass the poison to people who consume the commodity,” local Gapki secretary Timbas Ginting says.

“Furthermore, all ISPO-certified companies are prohibited from using insecticides, and if they still do, they are on their own,” he adds, referring to the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil system introduced in 2011 as a mandatory certification.

The scheme is intended for all palm oil producers across Indonesia, the world’s largest palm oil producer that supplies more than half of the global market, as part of the government’s effort to maintain sustainability.

The dire situation will likely persist unless the government does much more to stop illegal sales of pesticides and crack down on companies that flout the rules on occupational safety and health among workers handling agricultural chemicals.

“Never underestimate illegal pesticides on the market if you care about their danger to the human body,” Erwin says. “The government should act fast, now.”

At oil palm plantations,

workers’ risks outweigh wages

Sukma, a 38-year-old single mother of four, shivered as she recalled one accident that happened at work in 2015 when she tripped and the 25-kilogram jerrycan she was carrying doused her with Gramoxone herbicide.

Realizing the potential danger from the chemical she was familiar with after 20 years working as a pesticide applicator for a plantation company, she ran to a nearby pond and jumped in.

For the next few hours, she was shaken to the core. But miraculously, she developed no signs of poisoning. She continued her job until six months ago, when the company’s doctor told her she had traces of poisonous chemicals in her blood.

Then, her employer reassigned her as a weed cutter, likely to reduce the risk of direct exposure to pesticides.

What worried her was that the doctor would not explain what the toxic substance in her blood was, or whether she had obtained it from the stream of herbicide she once fell into or when she was drenched in the accident with the jerrycan.

“I’m worried about what the chemicals in me may cause in the future,” she said. She is anxious because as a casual worker who earns Rp 59,500 (US$4.21) a day, she has no savings in case she becomes ill and needs medication.

The fear is reasonably founded given her age and long working hours, 7 a.m. to 2 p.m., in a plantation where agricultural chemicals abound.

Oliana, who has worked as a pesticide applicator for another private plantation company in South Labuhan Batu, North Sumatra, for three years, also has a harrowing story to tell. Her company does not cover its workers’ medical expenses, so when two of her colleagues who had worked for the company since 2011 were treated for pesticide poisoning in a hospital, they had to pay out of their own pockets.

“The doctor diagnosed poisoning in both my colleagues. It’s sad they had to pay the bill,” Oliana said.

Natal Sidabutar of the Organization for People’s Struggle and Empowerment (Oppuk), a civil society that advocates workers’ rights, says the massive use of pesticides in plantations throughout the province has caused serious health issues. Workers who spray the chemicals without proper protective clothing and equipment are directly exposed, while people who live in the area are also affected, albeit to a lesser degree.

It’s not that they are unaware of the health risks from the chemicals, but they either underestimate the menace or wear inadequate protective equipment. Victims usually show symptoms such as headaches, blurred vision, heavy perspiration, dizziness, restlessness, nervousness, heavy breathing, nausea, diarrhea, loss of appetite, irritation and irregular heartbeat. In North Sumatra, many women work as pesticide applicators in palm oil plantations.

“We have helped dozens of workers

who fell victim to pesticide poisoning.

Many of are women and casual workers,”

~Natal says

Their status as casual workers means that they do not have a legally binding contract and are not entitled to any benefits, such as health care. Although this is in violation of the 2003 law on manpower, many employers exploit the absence of law enforcement.

The plight of women workers in plantations in such places as Sumatra and Kalimantan is well-known. The World Rainforest Movement notes that in the development of large-scale oil palm plantations that leads to the displacement of indigenous or forest people, women are largely marginalized. They get only menial jobs that barely earn enough to make the ends meet.

“It’s high time that companies stop the recruitment system for pesticide applicators and raise the status of casual workers so that they can obtain the benefits they deserve for their risky jobs,” Natal says.

Dressed for the occasion: A worker sprays pesticide at PT Lonsum’s oil palm plantation in Tanjung Morawa, Deli Serdang, North Sumatra.

Dressed for the occasion: A worker sprays pesticide at PT Lonsum’s oil palm plantation in Tanjung Morawa, Deli Serdang, North Sumatra.

Pesticide applicators often defy the rule that requires workers to wear standard clothing and equipment that protects them from exposure to toxic chemicals.

| Writer & Photographer | : | Apriadi Gunawan |

| Managing Editor | : | Primastuti Handayani |

| Desk Editors | : | Pandaya, Imanuddin Razak |

| Art & Graphic Design Head | : | Budhi Button |

| Technology | : | Mustopa, Sandy Riady Hasan |

| Multimedia | : | Bayu Widhiatmoko |