Data breaches have become a contentious issue worldwide after Facebook, which has 137 million users in Indonesia, admitted that British political consulting firm Cambridge Analytica had harvested data of 80 million users. The Jakarta Post’s Safrin La Batu explores challenges and how the government will help protect citizens’ privacy online.

When people around the globe were fuming at news about British political consulting firm Cambridge Analytica harvesting their information from Facebook, local users generally couldn’t care less. When Facebook chief executive Mark Zuckerberg promised steps to better safeguard users’ data, local users did not celebrate either.

But the government, as it usually did when dealing with recalcitrant social networking websites in the past, threatened to block the platform here unless the social media juggernaut fixed the system.

Politicians and new media pundits seized the moment to amplify their call for new legislation on data protection. A crucial issue in their mind is how third-party companies should handle users’ information and how the business entities should be held to account.

Apparently, many social media users have no good grasp of how social media works, and they hardly know the rules of the game. So it was by no means surprising when only a few made noise on Facebook’s announcement that more than 1 million of the 80 million accounts that Cambridge Analytica mined belonged to users in Indonesia. In fact, this was really a big deal, because Indonesia was the third-most affected country after the United States and the Philippines.

Local users would take the scandal lightly. Akfina Daroini, a 25-year-old college student in Jakarta, for example, says she has nothing to worry about, because she puts no private information that could possibly affect her privacy on her Facebook profiles.

“I am not worried at all,” she says. “It’s not going to affect me.”

On her Facebook account, Akfina, posts pictures of her daily routines, such as her in the classroom or hanging around with friends. She also uses Instagram to review products and discuss online shopping.

Another social media user, Dariah, a 26 year-old private firm employee in Jakarta, also insists there is nothing to worry about as long as you do not put too much personal information on your account.

The two women define “private information” essentially as bank accounts, credit cards, home address and phone numbers. They may not realize that social media is a different world with a different set of rules. Anything there can become sensitive information.

The case shows how intricate a data breach can be. Cambridge Analytica, as the data harvester, gained the access by exploiting Facebook users’ vulnerability instead of hacking the system. This means that legislation requiring social media platforms to close loopholes in their systems would likely fail without users reducing their vulnerability.

Hugely popular platforms like Facebook, Instagram and Twitter track and amass information on their users’ online activities, posts, likes and comments as well as pages they follow.

All this information is neatly stored in their database under specific classifications, such as geography or hobby. The purpose is to provide advertisers, which are their main source of revenue, with an audience.

It is also meant to provide a better user experience. So without asking their individual users what kind of person they are, the platforms actually get to know their users by tracking their activities.

A copy of downloaded personal information from Facebook, for example, shows that the social media giant tidily archived a huge amount of users’ personal data, ranging from friends, people ever contacting them to such trivialities as events they attended. Facebook even goes as far as retaining all the contact numbers from the phones used to install the app.

“When we talk about data [gathered in social media] it’s behavioral data. For example, they amass [information] about what photos we like and what activities we love. This behavioral data is learnt and analyzed,” said Calvin Kizana, the creator of a social media application called PicMix.

“The business of social media [companies] like Facebook is trading in their users’ data. It’s like they sell you. They don’t sell you any product,” IT expert and digital media practitioner Eka Ginting says.

Huge impact

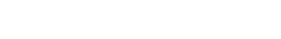

Germany-based online statistics firm Statista revealed recently that there were about 137 million Facebook users in Indonesia in 2017, making it the third-largest (along with Brazil) in the world. And this is just one social media platform. With this enormous number of users, social media have transformed into a powerful entity that no one can overlook.

Online consulting firm Digitroops found in a survey last December that social media had started to impact public policy. In fact, some Indonesian policies have been made out of pressure from social media users.

Digitroops CEO Fahd Pahdepie named the tax amnesty as a case in point. The program was initiated following a social media discourse that questioned the government’s inaction to recoup the billions of dollars wealthy Indonesians are hiding overseas to avoid taxes, as famously disclosed in the Panama Papers in 2016.

Organized by the Finance Ministry, the program aimed at boosting tax revenue by offering a lenient “rate of redemption” for taxes owed by individuals and companies.

As for politics, the new media influence is well known. In the US, the Cambridge Analytica data scandal is but one instance of how social media information is used to influence public opinion. In Indonesia, the social media was central in the campaign to bring down then-Jakarta governor Basuki “Ahok” Tjahaja Purnama last year with allegations of blasphemy.

Ahok, a Christian of Chinese descent, looked set to win another term until his political foes successfully exploited his gaffe on a Quran verse in 2016. After intense smear campaigns in the streets and in social media, Ahok lost his reelection bid, was prosecuted and sentenced to two years for blasphemy.

In recent months, as the 2019 general election draws nearer, smear campaigns on social media have been targeting top politicians like President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, who recently declared war on fake news.

Interestingly, the Indonesian government also seems not to care much about the revelation that data of more than 1 million Indonesian users were among those harvested by Cambridge Analytica. Instead of raising the issue, Communications and Information Minister Rudiantara advised Facebook to be mindful about being used to spread hatred ahead of the 2019 election.

“Let me tell you the government will not hesitate to block Facebook

if we think it’s necessary to avoid [incidents like] what is happening

in Myanmar, where Facebook is used to incite hatred,”

~Rudiantara, Communications and Information Minister

Legal framework

The Facebook scandal has prompted some countries to issue new legislation specifically regulating private data. The European Union, for example, has introduced online privacy rules billed as the world’s strictest, with the aim of giving internet users more control.

Indonesia is also working on a bill to better protect users’ online data, but there is skepticism about the government’s ability to enforce it.

IT expert Eka Ginting says that, for a new law to be effective, the government will have to do a lot of technical work that it may not have the means for.

“For example, the New York transportation agency has a regulation about taxi fares. So, if Uber, for example, releases a new [application] update, the agency will have to examine the source code and check if Uber is hiding information about discounts, etc.,” he says. “Can we [Indonesia] do such a task here?”

Eka argues that too many rules could also curtail the development of the digital technology that has brought about revolutionary innovation to humankind. And this achievement has been made possible by the internet’s boundless nature.

“The whole essence of the internet is its independence, its self-regulating [nature].”

For a country like Indonesia, where internet literacy is low and law enforcement is poor, the idea of regulating the internet is regarded as inefficient at best. Digital technology is advancing fast while lawmaking is a time-consuming process.

So, ideally, Eka suggests, the most effective “sanctions” for dishonest data processors and social media developers should come from the internet community.

“The user community has the responsibility to block any suspicious applications. That’s the essence of the #DeleteFacebook movement […] It’s what the ‘old internet spirit’ is all about,” Eka says. The government was advised to function as a mitigator rather than a regulator.

Beside the much-awaited data protection bill, the government is floating an idea of establishing a digital protection agency that will handle reports on data theft.

At the end of the day, it is the users who bear the utmost responsibility to safeguard their own data. Internet literacy is becoming ever more important for local users who need to develop a new media comprehension beyond chatting.

The much-awaited data privacy law

The government has vowed to put more effort into finalizing the drafting of the data privacy bill following the outbreak of the recent Facebook data-mining scandal. This is a progressive move designed to ensure greater internet privacy protection for Indonesians.

However, it is unlikely that Indonesians will see the law very soon. Bureaucratic processes and vested interests in the House of Representatives are likely to prevent the bill from being passed before next year’s elections.

The government and the House have been pointing fingers at each other after the public questioned why it took so long to process the bill, which has been a draft since 2016. The bill is not even on the House’s 2018 National Legislation Program (Prolegnas) — the list of priority bills to be discussed.

The government on the one hand has accused the House of not approving the bill in the 2018 Prolegnas. The House, meanwhile, retorts that the government did not propose the bill to be included in the 2018 list.

“We are waiting for Pak Rudiantara [the communications and information minister] to propose the bill to the House. We will surely process it,” said Meutya Hafidz, a lawmaker from the House Commission I overseeing defense, foreign and communication affairs.

Intensive discussions within the government have been held. Yet, some provisions in the data privacy bill overlap with the existing Civil Administration Law, thus discussions with the Home Ministry also need to be held in order to harmonize the overlapping provisions.

“The Civil Administration Law is on the books, I think if we can adapt [it] to the data privacy [bill], the problem will be solved,” Home Ministry population and civil registration director general Zudan Arif Fakrulloh said after a meeting with lawmakers recently.

The data privacy bill is near completion. However, deliberations at the House will involve yet another lengthy process. Take a look at, for example, the Criminal Code bill: The government proposed the bill to the House in 2012 but its deliberations are still underway today.

Critics claim that deliberations at the House are very political with some bills being prioritized based on lawmakers’ vested interests. Discussions about the Criminal Code bill, for example, had been very intense recently, but suddenly stopped. Analysts predict that the issue will become a hot topic again ahead of the 2019 presidential election.

The data privacy bill is regarded as an important element in protecting the growing number of Indonesians accessing the internet, especially on social media.

A copy of the bill seen by the Jakarta Post shows that several provisions, overall, seem to follow the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). For example, a provision about data subjects’ rights to ask for data deletion is equivalent to the “right to be forgotten” provision in the GDPR.

The bill, when it eventually becomes law, will affect data-processing institutions and other companies that retain users’ data, such as Facebook, Twitter and Google. The companies are required to provide a secure environment to protect users’ privacy. Article 13 of the bill requires a data-processing company to put forward technical details on how it will secure its users’ data. If a company is found guilty of violating the law, it can receive administrative punishments, such as part of its operations being frozen or paying a fine of up to Rp 25 billion (US$1.7 million).

Unlike prevailing laws, which limit private data to sensitive information such as identities and financial and medical histories, the bill defines private data in a broad and unlimited sense comprising all information about a person including his or her political views.

The bill also requires data processors and controllers to obtain written consent from data subjects before collecting data. In asking for permission, data processors should provide detailed information to data subjects about types of data to be collected, the purpose of the data collection as well as how long the data will be retained.

Data transparency is also regulated in the bill. Data processors are obliged to provide access for data subjects to see what information on them is being retained. Data owners can request to delete or change this information at any time. In addition, data processors are required to inform anyone affected in cases of data breach.

The Institute of Policy Research and Advocacy (Elsam), which often campaigns for data privacy, said in a recent statement that the potential for data leakages is increasing along with data-gathering activities, hence legal protection is urgently needed.

“Although data-gathering activities stick to anonymity principles, the risk of data leakage and abuse, which could identify individuals, is great,” Elsam said in a statement.

In an interview with the Post recently, Meutya Hafid said the bill would not imitate the GDPR as it will provide some leeway for new media businesses to grow.

“We are not going to follow [the footstep of GDPR]. We are not going to be that rigid. We want to see businesses grow well,” Meutya said without elaborating on the provisions that would differ from the GDPR.

Another matter regulated in the bill is the establishment of a special commission tasked with protecting data privacy. The name is not yet specified, however its duties will include ensuring that data processors obey the law, monitoring of data collection by processors, as well as assisting any individuals affected by data abuse.

World in hand: Communicating in the modern, digital era has been made easier through numerous social media platforms.

However, such social media platforms

World in hand: Communicating in the modern, digital era has been made easier through numerous social media platforms.

However, such social media platforms

have associated risks as users’ personal data and information are prone to abuse by anyone with access to the data and information. (JP/Ricky Yudhistira)

| Writer & Photographer | : | Safrin La Batu |

| Managing Editor | : | Primastuti Handayani |

| Desk Editors | : | Pandaya, Imanuddin Razak |

| Art & Graphic Design Head | : | Budhi Button |

| Technology | : | Mustopa, Sandy Riady Hasan |

| Multimedia | : | Bayu Widhiatmoko |