The maleo, a bird endemic to Sulawesi, is on the brink of extinction as a result of poaching and a shrinking habitat. The Jakarta Post’s correspondent in the Central Sulawesi provincial capital of Palu, Ruslan Sangadji, takes a closer look at how land conversion, egg theft and international support may make or break conservation efforts.

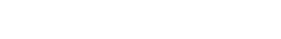

Among other birds in Sulawesi, one of the Indonesian islands within the Wallacea biogeographical realm, the maleo stands out for its distinctive build and colors — it is so distinctive that the bird has been designated the official bird of Central Sulawesi.

Its crown is ornamented with a black casque and its tail stands upright. An adult maleo is the size of a domestic chicken, at about 60 centimeters long and 1.6 kilograms in weight. It has dark plumage on its upperparts and white-orange underparts. Its facial skin is yellow, its beak orange and casque black. Males and females look similar; males are slightly larger and their colors brighter.

The monogamous maleo lives in hill and lowland forests. The species is vulnerable to predators and poaching as it lays eggs in open sandy river banks, coastal areas or lagoon beaches. The bird can lay eight to 12 eggs a year. Accompanied by its male, the female digs a deep hole in the sand to hide her egg, which depends on natural heat, such as hot springs or geothermal energy, for incubation.

According to bird conservation group Birdlife International, this distinctive megapode is listed as endangered because its population has been in rapid decline. This downtrend is feared to continue due to habitat loss and poaching. The bird population in the wild is estimated at between 8,000 and 14,000.

But, increasingly, the birds’ most dangerous “predator” is the human. People capture the birds to keep them as pets, but egg poaching is more common. A maleo’s egg is five or six times bigger than a domestic hen’s — an extraordinary size that makes it a much-sought after commodity that costs up to Rp 200,000 (US$13.85) each. People poach maleo eggs to sell them as souvenirs.

The illicit business has only been growing along with the bird’s popularity as a tourist attraction. The birds are commonly found in the regencies of Sigi, Poso, Parigi Moutong and Banggai.

Herman Sasia, a maleo conservationist in Sigi, a 90-minute drive to the south from Palu, said there were two serious threats to the maleo — land clearing by villagers who need more farmland and poaching.

Many superstitious indigenous people believe that maleo is a bird of luck. Its eggs are highly prized as a sacrifice in religious rituals. Houses are built on the ground where eggs are buried, as there is the belief that doing so brings prosperity. They are believed to have medicinal properties. Others hunt the bird only to take its egg and gift it. Although the tradition still exists, it is on the decline, according to environmental activists.

“We [activists] often stumble upon snares in the forest, which we immediately destroy,” said Herman, a winner of Kalpataru, the most prestigious national honor awarded to individuals dedicated to protecting the environment.

Environmental crimes most commonly happen at sandy beaches, where poachers dig up maleo nests and steal eggs. As locals’ awareness about conservation is rising thanks to environmental campaigns, government authorities and NGOs have long noticed that poaching involves people from other areas.

Breeding

Unstoppable poaching and land clearing have made the government turn to breeding as the most viable option to preserve the majestic bird. Leading the way is the Lore Lindu Biosphere Reserve and National Park, 60 kilometers south of Palu. The breeding site is located in Saluki village, Sigi regency.

Egg poaching continues today but, suspiciously, there have been no official records on how many thieves have been apprehended. Dedy Asriadi, chairman of the park authority office, said people who stole maleo eggs were master thieves who knew exactly when guards were off.

Authorities have entrusted the security of the breeding ground to Herman Sasia and they can forgive him for egg theft, as he has several other duties at the park, which was designated a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in 1997. Herman recruited Saluki villagers as guards under the Maleo Claws task force.

Built in 1998, the breeding ground can take care of up to 150 maleo eggs collected from various nesting places in the area. The eggs are put in artificial nests patterned off natural ones found in the wild.

Since 2003, the breeder has released 76 young maleos into the wild, Herman said.

An egg usually hatches after 65 to 95 days. When a maleo chick reaches the age of 30 days, it is set free into the forest. The most ideal habitat is one where there is a hot spring, where the sand is warm enough for perfect incubation.

The 2,180-square-km Lore Lindu Biosphere Reserve and National Park is one of the largest mountainous rainforests in Sulawesi, spanning 90,000 square km. Lore Lindu altitudes range from 200 meters to 2,160 m above sea level, with an estimated 90 percent of forest being montane, allowing for a unique mix of mountainous flora and fauna.

Much of Lore Lindu’s flora and fauna is endemic to Sulawesi, which lies east of the Wallace Line — a faunal boundary line that separates Asia’s ecozones and Wallacea, a transitional zone between Asia and Australia. The imaginary line runs between Kalimantan and Sulawesi through the Lombok Straight. Asiatic species are found west of the line while, to the east, species of Asian and Australian origin thrive.

Lore Lindu is a popular ecotourist destination where visitors enjoy breathtaking scenery and, if they are lucky, have a chance at spotting Sulawesi’s indigenous animals, like maleos, anoas, tarsiers, babirusas and civets.

Threat of extinction

Locals’ rising awareness about conservation has led to the emergence of maleo breeding projects in Central Sulawesi. Besides the Saluki site, maleos are also bred in Sausu Piore village in Parigi Moutong regency. In Banggai regency, the project began in 2013 thanks to cooperation between the Natural Resources Conservation Agency (BKSDA) and mining company Donggi Senoro Liquefied Natural Gas as part of its corporate social responsibility plan.

“I don’t believe maleo will go extinct from Central Sulawesi unless it’s God’s will,” Governor Longki Djanggola said, expressing optimism over conservation efforts that have received strong grassroots support.

The maleo eggs hatched at the Sausu Piore breeding project are mostly those confiscated from poachers by BKSDA officers. “That’s why our level of productivity keeps changing,” Donggi Senoro LNG media relations officer Rahmat Azis said.

The BKSDA is responsible for monitoring the maleos that the project has set loose on 12,500 hectares of Bangkiriang reserve forest. Since its inception in 2013, the project has released 60 maleo chicks into the reserve forest.

At Sausu Piore, the hatching rate is far from optimal, presumably because many of the confiscated eggs are taken from their ideal hatching spots. Still, the rate is considered higher than that in the wild thanks to modern incubation technology.

At the Saluki breeding project, where eggs are collected from maleo nests, Herman reported that there was a high hatching rate. He once incubated 15 eggs, all of which hatched.

The rate of post-release survival is also higher because the chicks will not be released to the wild until they reach the age of 30 days, when they are strong enough to evade predators and poachers. The longer chicks are raised in a breeding plant, the greater their dependence on humans is. “An older maleo would make the breeding project its comfort zone and it would take much longer for it to adapt to its new environment when it is released,” Rahmat said.

The Sausu Piore project has been recognized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) for its high-success hatching rate.

Unless the conservation efforts supported by the government, NGOs and communities succeed, Sulawesi may lose its majestic mascot.

Big is beautiful: Conservationist Herman Sasia says a maleo’s egg is up to six times bigger than a domestic hen’s. (JP/Ruslan Sangadji)

Big is beautiful: Conservationist Herman Sasia says a maleo’s egg is up to six times bigger than a domestic hen’s. (JP/Ruslan Sangadji)

Learning faithfulness and perseverance from maleo

Eco-tourists visiting the Lore Lindu Biosphere Reserve and National Park can consider themselves lucky if they see animals endemic to Sulawesi, such as babirusas, anoas, maleos, tarsiers and Tonkean macaques, in their natural habitat.

Only 320 maleos are estimated to remain in Lore Lindu, their largest natural habitat on the island, which sits on the Wallace line.

Particularly fascinating is the maleo. The unique bird that is central to the local culture is at the brink of extinction, ironically because of humans’ admiration of it. For generation after generation, locals considered it a creature of good luck, and they would steal its eggs to be used chiefly in traditional rituals or sold as mementos. Its elegance and beauty are so appealing that people want to own it so that they can adore it as a pet at home. In the past, when its population was larger, people hunted the big birds, which prefer walking rather than flying, for their meat.

Philosophically, one thing that locals would muse about this majestic bird is probably faithfulness. Maleos are known as monogamous and only death can end their “union”. Adult maleos live in pairs. The male will fight to the end against any males that make amorous advances toward his partner. If one of them dies, the other will live a solitary life until another love of its life eventually comes.

A maleo is sexually mature at the age of about two years and can produce eggs until the age of 20 years.

Single males fight for a single female. It may happen that a female has to go solo for months or even years before a victorious male takes her as his prize. This situation delays the animals’ reproductive cycles, leading to the species’ dwindling population.

“A maleo will never lay any egg after its partner dies until it finds another male,” says Dedy Asriadi, chairman of Lore Lindu’s technical section.

“A small population means that solitary maleos need a very long time before they find a new partner.”

When the female is ready to lay an egg, the pair will fly out of the jungle and find its historic breeding ground at sandy beaches by a river, lagoon or coast. At temperatures between 32 and 34 degrees Celsius, sand in Sulawesi coastal areas make ideal breeding grounds for maleos.

A pair usually digs three holes but only one is used to lay an egg; the others are meant to distract predators. In one nest, usually about 60 centimeters deep, the female lays a single egg which can be six times bigger than that of a domestic hen.

When being laid, the egg is soft and elastic. It hardens only after it comes out of the ovary.

This explains why a maleo, which is the size of a domestic hen, is able to push it out without too much difficulty.

The male patiently stands by the nest. Once the egg is laid, he will in turn cover the nest with sand and sometimes camouflage it with other debris. Once done, the pair will fly back to the jungle, forget the egg and never return to check the nest.

Unless it is stolen by a predator or thief, the egg will hatch after 60 to 90 days. The fully developed chick will struggle to rise above the surface. This is the very first real-life drama that the baby maleo has to go through. Many do not make it and die.

According to Herman Sasia, a maleo conservationist, it takes the chick up to 48 hours to break free from the sand.

Once it reaches the surface, the chick is completely on its own. The first law of the jungle it has to abide by is “fly or die”. An unlucky newborn may end up in the belly of a python or a cat, or in the hands of a poacher.

Hidden treasure: A conservationist shows a maleo egg he found in a breeding ground at Bogani Nani Wartabone National Park in Gorontalo.

Hidden treasure: A conservationist shows a maleo egg he found in a breeding ground at Bogani Nani Wartabone National Park in Gorontalo.

A maleo can produce up to 165 eggs in the course of its lifetime. (JP/Syamsul Huda M.Suhar)

| Writer | : | Ruslan Sangadji |

| Photographers | : | Ruslan Sangadji, Syamsul Huda M.Suhar |

| Managing Editor | : | Primastuti Handayani |

| Desk Editors | : | Pandaya, Imanuddin Razak |

| Art & Graphic Design Head | : | Budhi Button |

| Technology | : | Mustopa, Sandy Riady Hasan, Adri Putranto |

| Multimedia | : | Bayu Widhiatmoko |