Governments have come and gone but none has managed to lead Indonesia, which once prided itself as an agrarian nation, to self-sufficiency in food as it has always aspired. It was only in 1984 under then-president Soeharto that Indonesia made the dream come true before it slid back into the jaws of insufficiency. Presidential candidates Joko “Jokowi” Widodo and Prabowo Subianto have both raised the contentious issue on their campaign trails. The Jakarta Post writers Safrin La Batu and Pandaya explore what stands in the way of the country’s effort to end its reliance on food imports.

Last month, Jokowi’s senior aides raised a ruckus — again. This time, it was about the importation of 2 million tons of rice. The hottest scene was a mud-slinging match between Trade Minister Enggartiasto Lukito, who want-ed to keep the national rice supply at a safe level, and State Logistics Agency (Bulog) chief Budi Waseso, who opposed the policy because Bulog’s rice stock was sufficient to meet public demand until December.

Enggartiasto said he was aghast to find during “field checks” that only 903,000 tons of rice were in Bulog’s warehouses, far below the minimum stock requirement of 1.8 million tons. Budi, however, insisted that stocks were so abundant that he had been compelled to rent additional warehouses to store rice previously imported by the government. Budi reckoned that if the upcoming harvest season was taken into account, Indonesia would probably not need to import rice until June 2019 — an opinion shared by the Agriculture Ministry.

The polemic stemming from the notoriously chaotic statistical system and political strategy ahead of next year’s election has left the public at a loss about which version is right. By and large, it was symptomatic of the Jokowi administration’s inability to fulfill its promise of food self-sufficiency.

Moreover, rice is just one of the many commodities that Indonesia imports to supplement its inadequate food stock or to supply commodities not produced in the country, such as wheat. The dependence covers practically all commodities, from dental fillings to automotive products. The addiction to imports has been blamed for the country’s trade deficit.

Jokowi and his deputy Jusuf Kalla were elected in 2014 on a promise of food sufficiency as encapsulated in their nine-point Nawacita pledge. Through the National Economics and Industry Committee (KEIN), they in-troduced a road map on how they would pave the way to food self-sufficiency by 2045.

The road map serves as a guideline for Indonesia to achieve food sovereignty, starting with reducing dependence on imports and bolstering domestic products. It sets specific targets to achieve in certain periods. Under the grand plan, Indonesia is expected to achieve self-sufficiency in rice, shallots and chili in 2016; corn in 2017; soybean and household sugar in 2019; industrial sugar in 2025; beef in 2026 and garlic in 2033. Indonesia hopes to achieve its end goal of becoming one of the world’s “food barns” by 2045.

Missed targets

In the course of Jokowi’s first five-year term, his administration has focused on the cultivation of three basic commodities: rice, corn and soybean — promoted as the “Pajale scheme”. As the latest Cabinet bickering shows, Jokowi has missed the first three years’ targets. In 2017, Indonesia still imported 400,000 tons, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), albeit down from 1.3 million tons in 2016. Between 2013 and 2015, the country imported some 900,000 tons of rice a year.

Likewise, local farmers can meet only 35 percent of market demand for soybean to make tempeh and tofu, the most affordable sources of protein, despite the Pajale scheme. To make up the shortfall, the government imported 589,000 tons last year, an 11 percent increase from the 527,000 tons worth US$237 million in 2016.

Last year, Indonesia imported 379,000 tons of cane sugar worth $174 million, mostly from Thailand and Australia, making it the world’s second-largest sugar importer. As ironic as it may seem, even cassava — which grows easily in arid soil — has to be imported too. In 2017, Indonesia spent $10.5 million to import 32,500 tons of it from Thailand and Vietnam.

Imports of corn, a main ingredient of animal feed, hit 330,000 tons, Statistics Indonesia (BPS) data shows.

Despite its reputation as a vast and fertile tropical land where anything grows, a web of complicated cultural, political and economic problems have made Indonesia highly dependent on imports.

Jokowi’s Pajale scheme, which encourages farmers to grow rice, corn and soybean, has been widely seen as stifling their freedom to plant a variety of food crops most suitable in their areas and that best suits their needs. For decades, the government policy has encouraged people to consume rice as a staple food, disregarding the fact that regions boast their own “indigenous” diets. In Papua, for example, locals have tubers and sago, while in East Nusa Tenggara people traditionally subsist on corn.

Dysfunctional irrigation systems have long been identified as a major problem that hinders food self-sufficiency efforts. This year, the government allocated Rp 24 trillion ($1.6 billion) to fix broken agricultural infrastructure, especially irrigation systems in Java.

Public Works and Housing Minister Basuki Hadimuljono has acknowledged that irrigation channels across 4 million out of 7.3 million hectares throughout the country are functional and the rest are in dire need of repairs.

Shrinking farmland

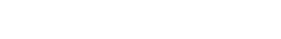

Geographically, Indonesia may be one of the largest countries on the planet with a land area of 181.157 million hectares, but its total farmland accounts for only 31 percent, or 57 million hectares, according to the FAO.

The proportion is smaller than that in neighboring countries with significant success in agriculture, a recent study by the Indonesian Center for Policy Studies (CIPS) found. Thailand, for instance, has allotted 43.3 percent of its land for agriculture, Australia 52.9 percent, China 54.8 percent and Vietnam 36.6 percent.

Thailand and Vietnam are world’s top rice exporters. Thailand exported an estimated 10.9 million tons last year, while Vietnam exported 6.9 million tons, according to the FAO. Australia and China, meanwhile, are also agri-culture powerhouses.

Given its huge population, Indonesia will have to reserve more of its land for farming to increase its agricultural-land-per-person ratio. Currently, Indonesia’s ratio stands at 1: 0.22 ha, lower than that of Thailand at 1:0.32, Australia 1:16.67 and China 1:0.32.

“The challenge for Indonesia to reach food self-sufficiency is not just the decreasing agricultural land. The number of workers in the agricultural sector is also shrinking,” said Hizkia Respatiadi, a researcher with CIPS.

The increasing conversion of agricultural land across the archipelago has caused major concerns. Every year, thousands of hectares of productive land are converted into housing complexes, large-scale oil palm plantations and industrial estates. The trend has commonly led to conflicts over land ownership that pits impoverished farmers against powerful businesspeople.

Bekasi regency, dubbed one of Indonesia’s rice barns, loses about 1,500 hectares of farmland a year to housing and industrial projects. The Agriculture Ministry has reported that farmland loss reaches a rate of 100,000 ha annually, way higher than the 40,000 ha of new farmland that the cash-strapped government can open up.

In urban proximities, it is more profitable to develop land into housing complexes and industrial estates than into agricultural projects.

As land ownership keeps dwindling, more and more younger educated people are leaving their villages to work in cities and on major plantations on the outer islands. Unlike in such developed countries as the United States and in Europe, in Indonesia farming is perceived as a lowly profession that promises a bleak future. Farmers are left without incentives and proper protection from the government.

Last month, Agriculture Minister Amran Sulaiman sounded the alarm on the declining number of farmers. Every year, Indonesia loses 2 percent of farming families and 65 percent of farmers aged about 65 years.

Rural families continue to decline in number, according to BPS. In 2003, they numbered 31 million and dropped to 26 million in 2013. “We ought to change the younger generation’s perception about farming so that we can be great again as an agrarian country,” said senior BPS statistician Momon Rusmono.

The downtrend has been confirmed by an NGO, the People’s Coalition for Food Sovereignty (KRKP). In a recent study, it found that only 37 percent of rice farmers’ children in Bogor, West Java, wanted to follow in their parents’ footstep, while the remaining 63 percent wanted to pursue different careers.

“Young people are generally more creative. They should have roles in the farming [industry],” says KRKP coordinator Said Abdullah.

Food self-sufficiency remains high on the agenda of the two presidential candidates, Jokowi and Prabowo.

Jokowi aims to finish what he started if he wins a second and final term in office. Among his signature programs is the building of 19 irrigation reservoirs in addition to the 46 he has already completed — all will cost Rp 70 trillion.

“He is on the right track,” claims Maman Imanulhaq, a director of Jokowi’s campaign team.

Prabowo, while criticizing Jokowi’s policy on imports, is promising millions of new jobs in the agricultural sector. One of his plans is to turn 80 million ha of deforested land into farmland as part of his food self-sufficiency efforts if he wins the election.

A crucial issue that both candidates have yet to address is the infamous cartel-like practices in the food importation business. The Business Competition Supervisory Commission (KPPU) is expected to crack down on the so-called “import mafia”, organized groups that exploit loopholes in the government system for gain.

The government’s failure to achieve its first targets is disappointing indeed, but the road map to food self-sufficiency gives a sense of direction and raises hopes for the restoration of Indonesia’s pride in being an agrarian country.

Luring the young back to farming as agriculture loses appeal

Despite Indonesia struggling to achieve food self-sufficiency, farming continues to haemorrhage the young blood it desperately needs if the country’s agricultural sector is to regain its past glory.

The government and other stakeholders realize the need to change the negative perception, especially among millennials, about farming being a back-breaking, lowly paid job that promises no bright future.

A group of activists from various organizations concerned about the decline in agriculture have begun trying to turn the situation around and make agriculture and agribusiness more attractive for younger people.

To start with, they have selected 30 applicants who convinced the recruiters of their strong interest in ag-riculture. The 10 best trainees will be appointed as “young farmer ambassadors” and entitled to more intensive mentoring on modern farming techniques and agribusiness. Also, they will serve as liaisons, acting as bridges between farmers and investors.

“We selected innovative young people to help restore the image of agriculture,” said Dedi Triady, the country coordinator of AgriProFocus Indonesia, one of the initiators of the Young Farmer Ambassadors program.

“We want to strengthen their capacity for doing business, networking and personal development.”

To qualify for the ambassadorial post, candidates need to produce sound evidence showing they have an innovative mind-set, such as by adding value to raw agricultural products, making the best of technology and maximizing productivity. In short, they must have the skills and proficiency to show the younger generation that farming can be a profitable enterprise.

Kebun Kumara is a 300-square-meter garden in Ciputat, Banten. Cofounded by Siti Soraya Cassandra and Dhira Narayana, it can earn up to Rp 100 million (US$6,611) a year from the sale of organic plants.

Thanks to the success story, the garden has been destined as an education plot for young people to learn about agriculture and agro-preneurship.

“I have never heard about a child who aspires to become a farmer or fisherman,” Siti says in petanimuda.org, a platform created to inspire young people to become farmers.

The innovative campaign targeting the young came amid reports of young people migrating from villages to ur-ban and industrial centers for better-paid jobs. More and more young people are uprooted from their agrarian base.

A recent study by the People’s Coalition for Food Sovereignty (KRKP) found that 63 percent of the children of rice farmers in Bogor, West Java, did not want to follow in their parents’ footsteps. Similarly, 53 percent of the children of horticultural farmers in the municipality did not want to become farmers.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), a growing number of young people in Indonesia choose to leave villages where their parents are farmers as they no longer see any incentive in the profession.

Over the past 15 years, urban areas in Indonesia have grown by 50 million people, while the rural population has shrunk by 5 million, according to the organization. In 2016, at least 7 million people migrated from rural to urban areas.

In its 2013 national survey, Statistics Indonesia found that 60.8 percent of more than 26 million farmers aged 45 years and older, and more than 70 percent of all farmers had only an elementary education.

The FAO advises governments to offer incentives to farmers otherwise all efforts to keep young people on their farms will be doomed to fail. It suggests that the government show that farming can be profitable.

“The young generation is urgently needed in rural areas. To stem the flow of migration out of the rural areas, we have to provide the right incentives, and demonstrate that being engaged in agriculture can be profitable, and provide for a comfortable living,” says Mark Smulders, FAO representative to Indonesia and Timor Leste, on the organization’s website.

Engaging the young in agriculture needs innovation as shown by the alliance of farming campaigners. Just like in advanced countries, the Indonesian government will have to provide incentives, such as start-up capital and subsidized fertilizers, and protective measures so that local products can compete with imports in terms of af-fordability and quality.

Only if the government is able to prove that being a farmer is a truly rewarding profession will Indonesia be able to reclaim its fading reputation as an agrarian nation.

Young and curious: Dhira Narayana (left), cofounder of Kebun Kumara, explains to a group of students about his 300-square-meter “educational garden”.(Courtesy of Kebun Kumara)

Young and curious: Dhira Narayana (left), cofounder of Kebun Kumara, explains to a group of students about his 300-square-meter “educational garden”.(Courtesy of Kebun Kumara)

| Writers | : | Safrin La Batu, Pandaya |

| Managing Editor | : | Primastuti Handayani |

| Desk Editors | : | Pandaya, Imanuddin Razak |

| Art & Graphic Design Head | : | Budhi Button |

| Technology | : | Mustopa, Sandy Riady Hasan, Adri Putranto |

| Multimedia | : | Bayu Widhiatmoko |