Jakarta’s fury over the multi trillion rupiah in garbage disposal fees sought by its neighbor Bekasi should serve as a hard lesson to expedite the capital city’s overdue effort to reform its primitive, costly waste management system, which relies on a single landfill. Our reporters Vela Andapita and Safrin La Batu analyze the prospect of the modern waste treatment facilities Jakarta is soon to build.

“Unless we reach an agreement,” the visibly angry Bekasi Mayor Rahmat “Pepen” Effendi said, “the road blockade will continue. Never mind stopping their garbage trucks, I can shut the landfill down.”

Pepen made the incendiary statement at the height of his war of words with Jakarta Governor Anies Baswedan last month over the unsettled annual bills the Jakarta ad-ministration was supposed to pay in order to continue dumping its 7,000 tons of garbage a day in the Bantar Gebang site in Bekasi. On another occasion, he scoffed that Anies “had no knowledge about the history of partnership between Jakarta and its satellite cities”.

Dramatically reinforcing his demand that Jakarta soon settle the overdue Rp 2 trillion (US$136.23 million) it owed to Bekasi, Pepen blocked a road and held up 51 garbage trucks heading for the Bantar Gebang landfill. The measures stoked fears that Jakarta would stink because its fleet of 1,300 garbage trucks have no other place to dump the city’s waste.

Pepen reckoned that the grand sum of funds that Jakarta had to pay this year would reach a whopping Rp 2 trillion. Anies, however, maintained the total was actually “only” Rp 202 billion, consisting of Rp 138 billion in “compensation” money plus Rp 64 billion of carryovers from last year.

“[Pepen sounded] as if we were irresponsible, while in fact we have properly implemented the agreements,” Anies said.

The dispute was but the latest episode in the perpetual conflicts that lead the heads of the neighboring governments to give each other black eyes. They started during the administration of governor Sutiyoso (1997 to 2007) and continued through those of Fauzi Bowo (2007 to 2012), Joko “Jokowi” Widodo (2012 to 2014) and Basuki “Ahok” Tjahaja Pur-nama (2015 to 2017).

Anies has insisted the Rp 2 trillion that Pepen talks about was a “partnership fund” through which Jakarta contributes to other satellite cities for joint projects and “has nothing to do” with the garbage disposal. He said it was, in fact, non-obligatory and that the amount varied.

The commotion eventually died down after Anies and Pepen had lunch at the former’s office on Oct. 22. Few specific agreements were made public.

Jakarta and Bekasi forged an agreement on the 110-hectare landfill in 1989. Some 80 ha have been used up and the Jakarta Environment Agency expects the landfill is expected to reach its maximum capacity of 49 million tons by 2021. Currently, some 39 million tons of garbage are forming stinky hills that swarm with flies on the once flat land.

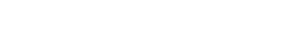

A waste of money

Bantar Gebang’s dwindling capacity, the continual conflicts and the massive costs have given Jakarta a splitting headache. Suffering environmental and health consequences, as well as knowing Jakarta’s vulnerability, Bekasi knows only too well how to play its cards, as Pepen is doing these days, to rake in money from its wealthy neighbor.

Every year, Jakarta has to pay hundreds of billions of rupiahs in “compensation” and “grants”, besides covering the costly logistical and operational costs of its garbage fleet. “Compensation”, better known as “stink money”, is provided to Bantar Gebang residents directly affected by the waste, while “grants” or a “partnership fund” is the money that Jakarta contributes to its satellite cities to be used for projects that also benefit Jakartans.

This year, Bekasi initially proposed receiving Rp 2.09 trillion in grants from Jakarta, but revised the figure down to Rp 545 billion after Anies met with Pepen. Jakarta also promised to give Bekasi Rp 141 billion in “stink money” next year, far below the Rp 343 billion that Pepen demanded.

About 18,000 families around Bantar Gebang are entitled to the stink money made available since 2016, with each receiving Rp 300,000 every three months.

Over the past several years, Jakarta has made some efforts to improve its garbage management system and reduce its dependence on Bantar Gebang. The establishment of waste banks is one, where waste is separated into organic and non-organic components. Organic waste is used for compost and non-organic plastic, metal and paper — plus bottles — goes to recycling plants.

People who have accounts bring their filled bins to the nearest waste “bank” where they make a “deposit” of non-organic solid waste. The monetary value set by the garbage collectors is deposited in the people’s accounts, from which they can withdraw cash.

Waste banks have also been started in other major cities. In Jakarta, 267 subdistricts already have them as part of their efforts to create clean neighborhoods.

The endeavor is bearing fruit. For example, the RT 09 neighborhood in the Kembangan sub-district is cleaner now as most of its residents participate in the waste bank program. Once notorious for flooding, the area has been awarded for being one of the cleanest in West Jakarta.

“We’ve been trying to focus on [waste] reduction by, among other things, the establishment of waste banks,” Jakarta Environment “We’ve been trying to focus on [waste] reduction by, among other things, the establishment of waste banks,” Jakarta Environment Agency deputy head Djafar Muchlisin said in an interview with The Jakarta Post.

However, the success is insignificant. Waste banks alone are unable to solve the city’s garbage issue because they only buy specific types, such as plastic bottles.

Jakarta’s mid-term development plan (RPJMD) sets a target for reducing its waste to 1,050 ton a day. Still, the waste is too much for the banks to handle. For example, West Jakarta’s trash banks could only collect 295 tons of waste last year.

Moreover, incentives are far from appealing. According to Djafar, some families would need to work about three months to earn Rp 1 million from selling non-organic waste.

Modern treatment

Now Jakarta is turning to technology to manage its waste. In cooperation with Finland, the city will build its first integrated treatment facility (ITF) in Sunter, North Jakarta. City officials are finalizing the environmental impact analysis (Amdal).

“Bantar Gebang is under too much of a burden. That’s why we are going to build treatment facilities throughout Jakarta to phase out our dependence on the landfill and reduce the amount of garbage there,” Anies said.

The $250 million facility is to be built by city-owned developer PT Jakarta Propertindo (Jakpro), which is to join hands with Finnish energy company Fortum. The project is expected to commence this December or in January 2019, depending on how quickly officials can finish the environmental impact analysis.

“If everything goes as planned, the ITF in Sunter will start operating in 2021. Many have predicted that the Bantar Gebang landfill will run out of capacity in 2021 too. What a coincidence,” said Jakpro ITF project director Aditya Bakti Laksana.

The facility is billed as using a state-of-the-art, eco-friendly technology that would produce minimum residue. Fortum promises that 83 percent of the waste would be transformed into energy and the remaining 17 percent would form a residue that will be dumped in landfills. Talks have been underway with the state utility company, PLN, about the purchase of 35 megawatts of electricity from the plant.

“The incinerator can burn waste consisting of 60 percent water. Even organic waste from residences and traditional markets can be processed too,” Aditya said.

Jakarta is planning to build another three ITFs. The facility’s northern zone would have a daily processing capacity of 1,200 tons of waste, its western zone 2,400 tons and the eastern zone 1,700 tons. It is going to allocate Rp 2 trillion to acquire land for the tree plants next year.

The ITFs are to be built because of a presidential instruction issued in April, which requires that major cities across the country, such as Tangerang, Bekasi, Bandung, Semarang, Surakarta, Surabaya, Denpasar, Palembang and Manado, have waste treatment facilities.

However, not everybody is happy with ITFs. Critics warn of environmental and health haz-ards that come along with the toxic smoke emanating from incinerators fed with wet garbage.

It is Jokowi’s second attempt to make big cities build waste treatment plants. In 2016, a similar instruction, Presidential Regulation No. 18/2016, was annulled by the Supreme Court after various civic groups raised objections arguing that incinerators were dangerous to public health and the environment.

Burning garbage to generate energy is a waste-treatment technique introduced more than a century ago. A facility burns combustible waste and produces energy and two kinds of residue: gas that is released into the air and solid residue.

The United States began burning garbage with incinerators in the 1890s. It started as a measure to reduce the volume of waste, but incinerators in the US today also generate useful products like heat, steam and electricity.

In Japan, Tokyo has 21 incinerators to treat waste from its 23 wards, some of which are located in urban centers, like ones near Shibuya Station and Ikebukuro Station. Three facilities have been supplying energy for district heating and cooling systems.

Urban development expert Wicaksono Sarosa says it is high time for Jakarta to take a more sustainable approach toward waste management.

“Waste production should be controlled from the very beginning. It’s no longer 3Rs [reduce, reuse, recycle]; we need to apply 5Rs: refuse, reduce, reuse, repurpose and recycle,” he said.

“ITF can be one good measure to take, even though it might not be able to process all the waste, and the next challenge would be the maintenance of the facility.”

Children of landfill scavengers learn about life, values

About 30 children gathered on a recent Sunday in a small wooden house for their weekly English, drawing and yoga classes. The breeze blew a stench in from the mountains of garbage nearby.

The classes were a break from the children’s daily routine of helping their parents eke out a living as scavengers at Bantar Gebang, the largest landfill in the country. An estimated 6,000 scavengers rely on the 110-hectare dump for income.

The sheer stink can ward off unsuspecting strangers. Fat flies swarm all over the place. Roaring oversized dump trucks come and go.

Welcome to Biji-Biji Bantar Gebang (BGBJ), an informal school founded to help children of the impoverished scavengers catch up with modernity.

Activist Resa Boenard says she helped found the free school in 2014 out of concern about rampant child marriage. That is why teachers try to instil in students the understanding that child marriage is bad.

She recalls her family moved to Bantar Gebang years before the area was turned into a landfill in 1989. “Something told me I had to do something about it. This is my neighborhood.”

The school has no set curriculum. Subjects may range from health, nutrition and sports to art.

Resa loves to call the school a “community” where children are free to “come and have fun” without having to register.

The Indonesian word biji-biji (seeds) is used to mean that the school treats the students as “seeds of the future”. In the landfill community, education is the last thing that comes to people’s minds that are already preoccupied with meeting bare necessities.

Founders of the informal school also saw vulnerabilities, especially among the young children, to exploitation, especially prostitution. This has compelled them to offer alternative subjects such as personal development to boost their self-esteem. This is what makes the school different from the formal ones that emphasize cognitive development.

“We aim to provide alternatives for young people, giving them the tools and knowledge to break the poverty cycle and create a healthy and safe environment for themselves and their families,” the community writes on its website.

Children at the landfill are vulnerable to bullying because of their families’ low economic status, so they need to be empowered, Resa says. Even she herself falls victim to harassment. At her college, some call her “The Queen of Bantar Gebang”.

“I wouldn’t take the bully seriously, but not all children are be able [to cope with it],” she says.

BGBJ has some computers for the children to learn IT, but the problem is that no internet provider is willing to extend their services there; they will not take a risk of installing fibre optic cables through the garbage area. On IT, Resa says she wants to teach the children how to create a blog through which they can practice writing.

The school relies on volunteers who are willing to work for nothing. Among the instructors are foreign nationals who teach English. Lawrence Blackman is an Englishman who volunteers to teach his native language. Sometimes, he dances to entertain the kids.

Tongue twisting time: Volunteer Lawrence Blackman from Britain teaches English at the Biji-Biji Bantar Gebang (BGBJ), an informal school for the children of scavengers at the Bantar Gebang landfill in Bekasi, West Java. (Courtesy of Resa Boenard/BGBJ)

Tongue twisting time: Volunteer Lawrence Blackman from Britain teaches English at the Biji-Biji Bantar Gebang (BGBJ), an informal school for the children of scavengers at the Bantar Gebang landfill in Bekasi, West Java. (Courtesy of Resa Boenard/BGBJ)

Blackman, who intends to stay for a month with the landfill kids, says an informal school like BGBJ is important for children to learn “values” and “life”, the things the children might not get from formal education.

“A value is not [something] to learn from the book,” he says. “The two [formal and informal education] are working together.”

Dannie, a volunteer from China, is impressed with how the scavengers’ children enjoy life, without the luxury of toys or gadgets that well-off children cannot do without.

“They happily make do with simple things,” she says, showing photographs of children playing by piles of garbage at the landfill. “They have hope.”

Unfortunately, the presence of foreign nationals has led local Muslims to suspect them of “Christianization” of the children.

“It is a funny accusation. They should have asked the children if Christianity is taught,” says Resa, who is a Muslim.

So far, the allegations have yet to adversely affect the educational activity, something that is not envisioned by the government authorities now busy seeking fabulously high garbage disposal fees from Jakarta.

Fishy and dirty: Officers clean up the area around the Cilincing fishing port in North Jakarta. (JP/Wendra Ajistyatama)

Fishy and dirty: Officers clean up the area around the Cilincing fishing port in North Jakarta. (JP/Wendra Ajistyatama)

| Writers | : | Vela Andapita, Safrin La Batu |

| Photographers | : | Seto Wardhana, Wendra Ajistyatama |

| Managing Editor | : | Primastuti Handayani |

| Desk Editors | : | Pandaya, Imanuddin Razak |

| Art & Graphic Design Head | : | Budhi Button |

| Technology | : | Mustopa, Sandy Riady Hasan, Adri Putranto |

| Multimedia | : | Bayu Widhiatmoko |